At some point during the week-long interrogation that followed the announcement of Microsoft’s new Teletexbox, Xbox division head Don Mattrick made a quip about backwards-compatibility. I’m told he said it was “backwards”, and have every faith that it sounded as funny in his head as it wasn’t on his lips.

The truth is, it’s the backwards thinking of men like Mattrick that necessitates one of the PC’s most important functions – that of the living museum. The PC is the golem guarding gaming’s history; the only thing standing between countless brilliant, neglected games and an ignoble demise.

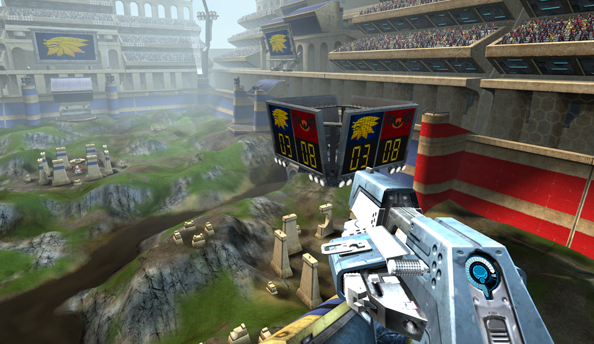

I’ve had a bit of an odd time this week, trying to find a way to play Tribes Vengeance. It was intended to reboot a beloved series – an FPS in which your feet only ever touched the ground momentarily so that you might fling yourself back into the air again. It was about playing Tiny Wings as a space marine wearing a jetpack. In 3D.

Somehow it was made by Irrational Games. For the first time, the Tribes series became the vehicle for a grand, sweeping, multi-perspective narrative, flush with kidnappings, class warfare, and bold females.

Or so I’m told. Vengeance sold like coldcakes, publisher Vivendi has long since given up existing, and copies are very hard to come by indeed. After a few hapless evenings spent typing ‘Tribes Vengeance buy where can I buy this game please’ into a generic search engine, I eventually uncovered a singular second-hand copy on Amazon. It will reach me at some point in the next 3-124 working days.

Why am I telling you this? Because it’s an incredibly unusual edge case. In an age where digital distribution has opened up the vaults like never before, it’s rare to see a game completely vanish. Over the last decade, Steam and Good Old Games have tracked down the last-known-whereabouts of much of the PC’s back catalogue. Publishers like EA, 2K and Bethesda have begun to warm to the idea of sticking their old games in a place where they can make them more money. Today, we have easy access to classic PC games that were previously only found on sites like Abandonia or Home of the Underdogs. Best of all, we’re promised that they’ll run without a hitch on modern systems.

Even those games left to languish in IP hell are, more often than not, available to those who truly wish to seek them out. When their boxed editions have all crumbled into dust, these games will live on in fan-created emulators. Take ScummVM – a platform originally designed to host those games which ran on LucasArts’ classic adventure game engine, now the contemporary home of a neglected genre. Or DOSBox – free software capable of propping up more-or-less any pre-Windows oddity you can remember on a modern rig. Funnily enough, it’s DOSBox that you’ll see bringing up the rear of some official re-releases on Steam and GOG.

Even games originally found only on Nintendo consoles now find their saviour in the PC. Because unless you’re Mario or Zelda and therefore subject to re-packaging on the eShop – if you’re Julian Gollop’s Rebelstar: Tactical Command for the Gameboy Advance, for instance – then console emulators, legally dubious though they are, are your conservation park.

What all of this means is that the ongoing existence of your favourite games, now and in the future, isn’t beholden to a single platform holder like Microsoft or Sony. Companies have shifting priorities. Their first responsibility is to their shareholders – not to any abstract ideal of gaming heritage. The PC allows us to document the history of our art without worrying about the whims of any one company.

But those publishers have to understand something: the past holds the key to our future.

From whence exactly do you think that horde emerged to buy Firaxis’ XCOM: Enemy Unknown in droves last year? If you answered 1994, I think you’re wrong. I’m willing to bet that, like me, a large proportion of that horde first played X-Com in 2001, 2008, or 2010, or 2012. They bought the whole series on Steam for £3 and, in a matter of months, became indistinguishable from the fanatics with two decades’ experience in baying for a worthy sequel.

Making your old games available to new people isn’t just an easy form of income; it’s effective guerilla marketing for those things publishers love best: sequels.

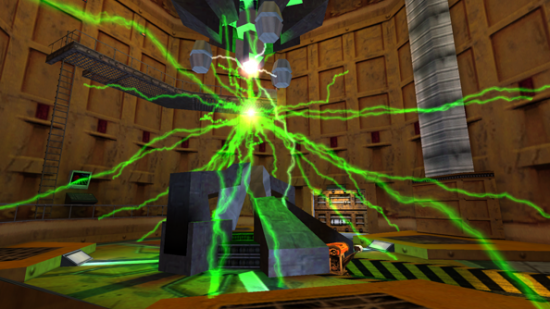

One last thing. I’ve just spent a very enjoyable weekend playing through Half-Life, from start to finish. In Don Mattrick’s world, that would be literally impossible without recourse to some ancient box, or the distant hope of an HD remake on Xbox Live.

Just imagine a world in which nobody could play Half-Life. Fail to hit puberty by 1998? Sorry. No Half-Life for you. For you, Half-Life will forever be a dry footnote, seen referenced in the Valve interviews you scour for news on Dota.

Forget City 17; that’s a real dystopia right there.