In this guide, we’ll show you how to make a custom keyboard. Rather than relying on a pre-built design, if you build your own DIY gaming keyboard you get an an endless amount of choice and customization options, and the ability to build a device with a truly premium typing experience.

I’m writing this feature on a device that not even the best gaming keyboard models can come close to replicating in terms of feel, sound, and general typing experience. What’s more, the overall design of my custom keyboard is unique. You can make your one a custom gaming keyboard, a typing device, or you could even try a completely non-standard layout and keymap to increase your typing rate or avoid repetitive strain injury.

Make a custom keyboard – the group buy

Because building a custom keyboard is still a comparatively niche hobby, the parts aren’t usually mass-produced. The components get made in low volumes instead and are therefore usually bought with what’s known as a group buy (GB).

This is where a designer will pitch an idea for a keyboard or some keycaps in a process called an interest check (IC). If enough people signal they’d be willing to pay for it, a GB is formed, so people can pitch in their cash and the designer can place an order, without taking on all of the cost. The designer then works with the manufacturer to take their idea to production.

It’s often a long and expensive process, but there are shops that sell more generic custom keyboard parts, with some keycap sets being easy to obtain without a long lead time or breaking the bank. Likewise, buying standard Cherry MX switches is easy and you can readily get hold of bare bones keyboards with a base and switches but no keycaps. It’s just that the end result won’t be as custom, nor as premium.

Given the economics of buying components individually and participating in group buys, it can get expensive. The keyboard used to write these very words is worth around $750 fully built, and that’s increasingly the kind of price you can expect from limited-run boards made by designers such as Smith and Rune, ProtoTypist, and LifeZone. There are designers who offer a discount in larger numbers, but it’s rare – the price is usually driven by rarity and quality.

As for where to find more information and get in on those GBs, Geekhack is your friend. It’s a site where designers post their interest checks for feedback during the design process, and then their group buy details if everything is successful. Also, check out the custom keyboard Reddit community.

Which custom keyboard cases, weights, and plates to use

There are six main components to a custom keyboard: keycaps, keyswitches, stabilizers, PCB, switch plate, and case. We’ll get to the first four in due course, but the last two provide the foundation of your custom keyboard’s design.

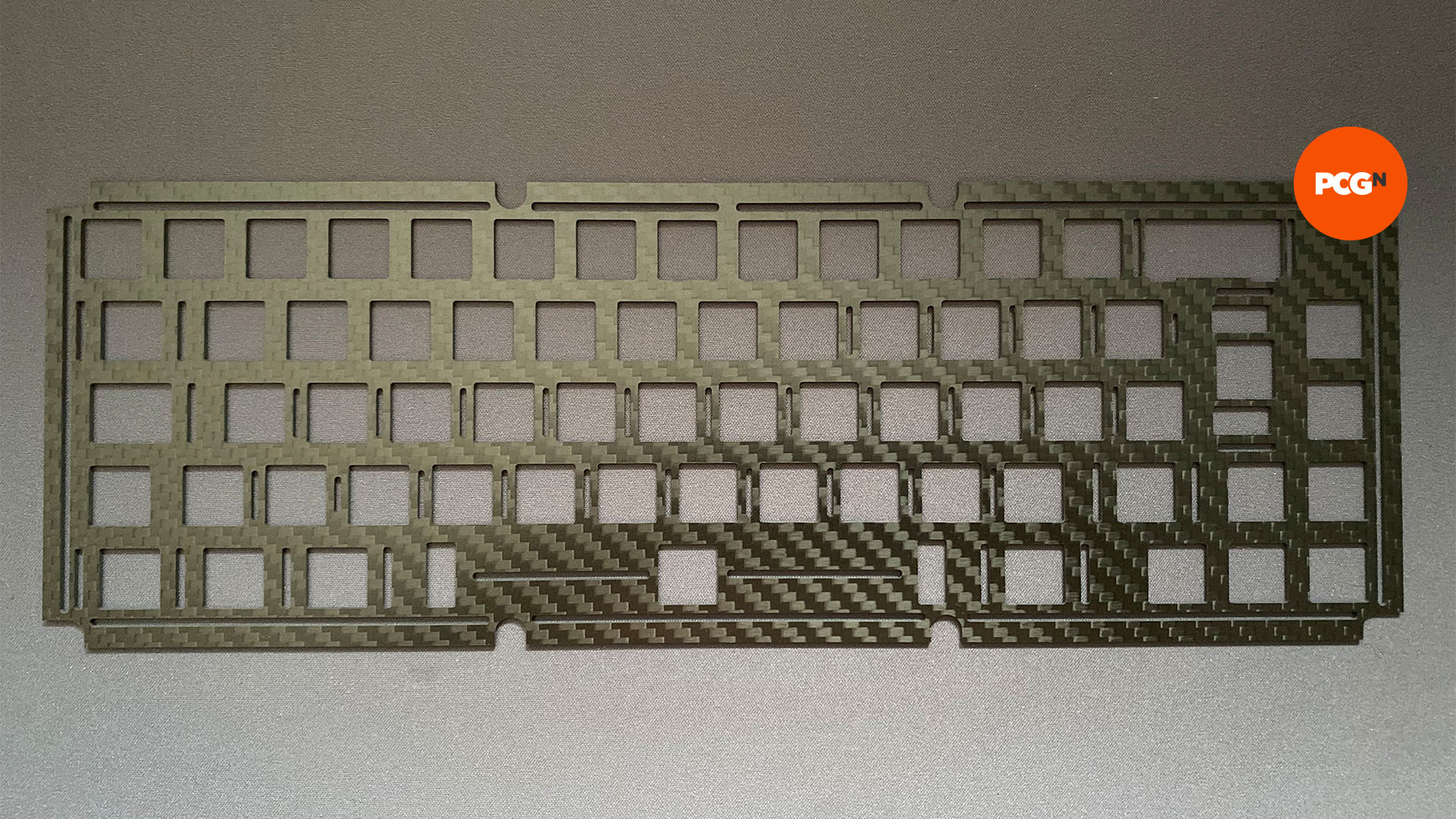

The switch plate is, as its name suggests, the central plate onto which the keyboard’s switches are mounted. The plate will either offer a single fixed key layout or some degree of variation, so you can choose the layout that suits you best. For example, on the keyboard I’m using now, the plate supports a handful of different possible layouts, including the common US ANSI and UK ISO layouts.

Often the plate is a separate physical piece from the case mounting to it, but sometimes the plate is integrated with the keyboard’s top case as a single piece. It can be easier to work with an integrated plate, but a separate one is usually more flexible. Regardless of which style the board uses, most custom keyboards are sold as a kit case, switch plate, and PCB kit.

As far as the overall shape of the keyboard, there are some common sizes, such as 60, 65, 75, and 80 percent (often called TKL) and full-sized (sometimes called 1800), all of which roughly refer to the size of the board relative to a full-sized, 105-key unit.

There are no absolute standards though, so always double-check exactly what you need. Likewise, for the key layout, there are some standards, such as US ANSI or UK ISO, but designers can and do play fast and loose with them, and there are many esoteric variations, such as ortho-linear layouts where all the switches are in line with each other.

Your choice of layout depends on how you intend to use your keyboard, and how you’re optimizing your workspace. I tend to choose smaller 60 and 65 percent boards since they provide more room alongside for a trackpad or mouse, and because I very rarely need a numpad or the F-row.

However, having tried a bunch of 60 percent boards, where you just get the core alphanumeric keys and modifiers, my preference has shifted towards 65 percent boards. Having an arrow cluster is very handy, and the handful of extra keys (Del, PgUp, PgDn, Home, End) are useful both in themselves and for mapping other functions.

Along with the layout, the material from which the case and plate are made are important factors. Plates that use hard metals, such as brass, will feel very rigid as you’re typing, and will sound different to aluminum. Non-metallic materials are increasingly common for plates too, especially carbon fiber and certain thermoplastics. Entire keyboard cases can even be made out of semi-transparent or dyed polycarbonates.

High-end keyboards also tend to come with internal weights to give them some heft and prevent them from moving around on your desk as you type, which affects how the board sounds. And while you may rarely look at the bottom of a keyboard, designers will often use weights to provide hidden external detailing.

The most common arrangement for a custom keyboard, called top mount, has the switch plate affixed to the top case, and then the bottom part of the case attaches to that assembly, but there are umpteen different variations. The most complex mounts in the hobby today are of the isolation variety.

They use layers of isolating material to surround the plate and effectively suspend it inside the case, so that when you’re typing, the noise isn’t transferred to the case material as much, and the feel is cushioned.

Which custom keyboard PCB to use

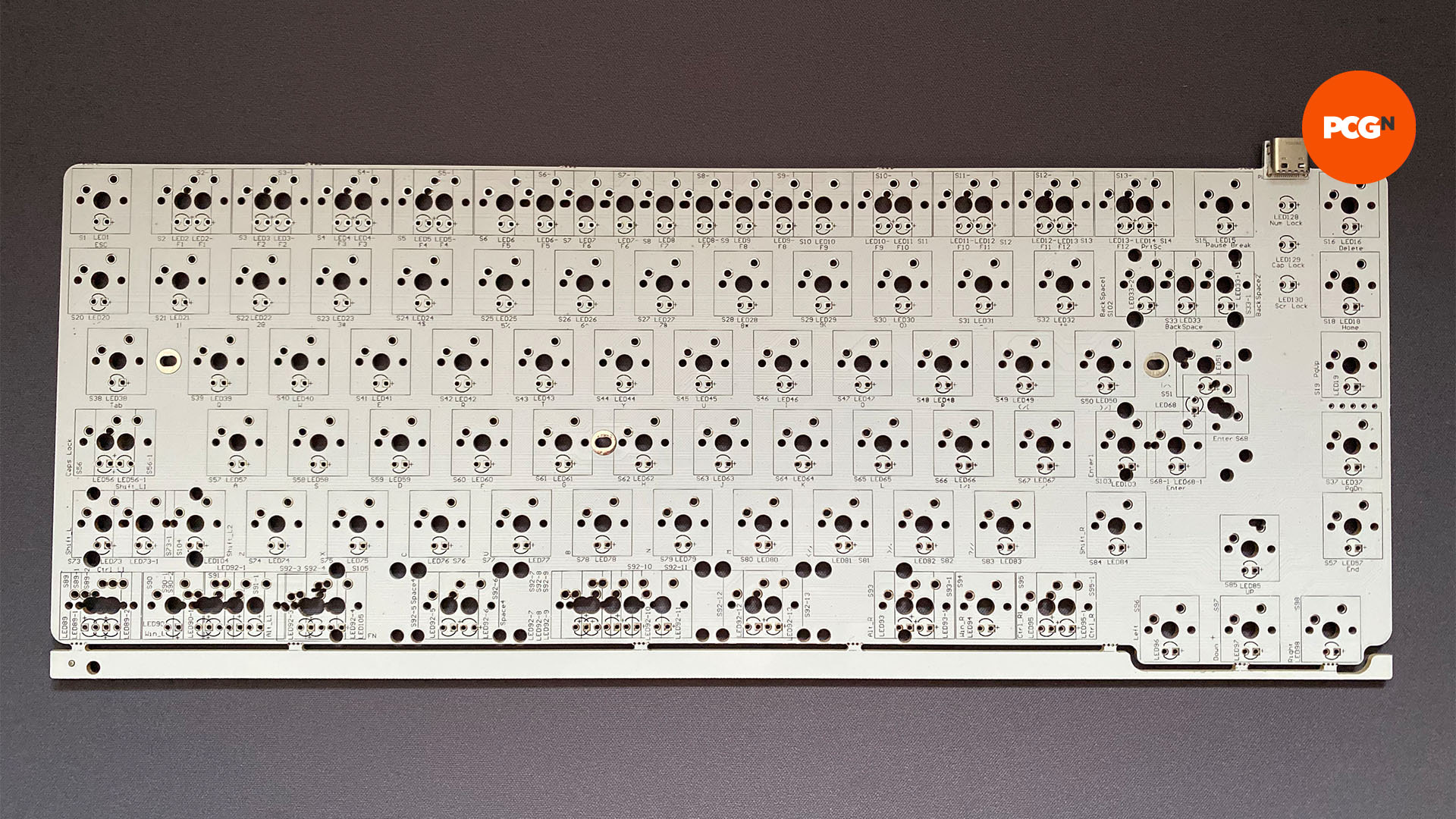

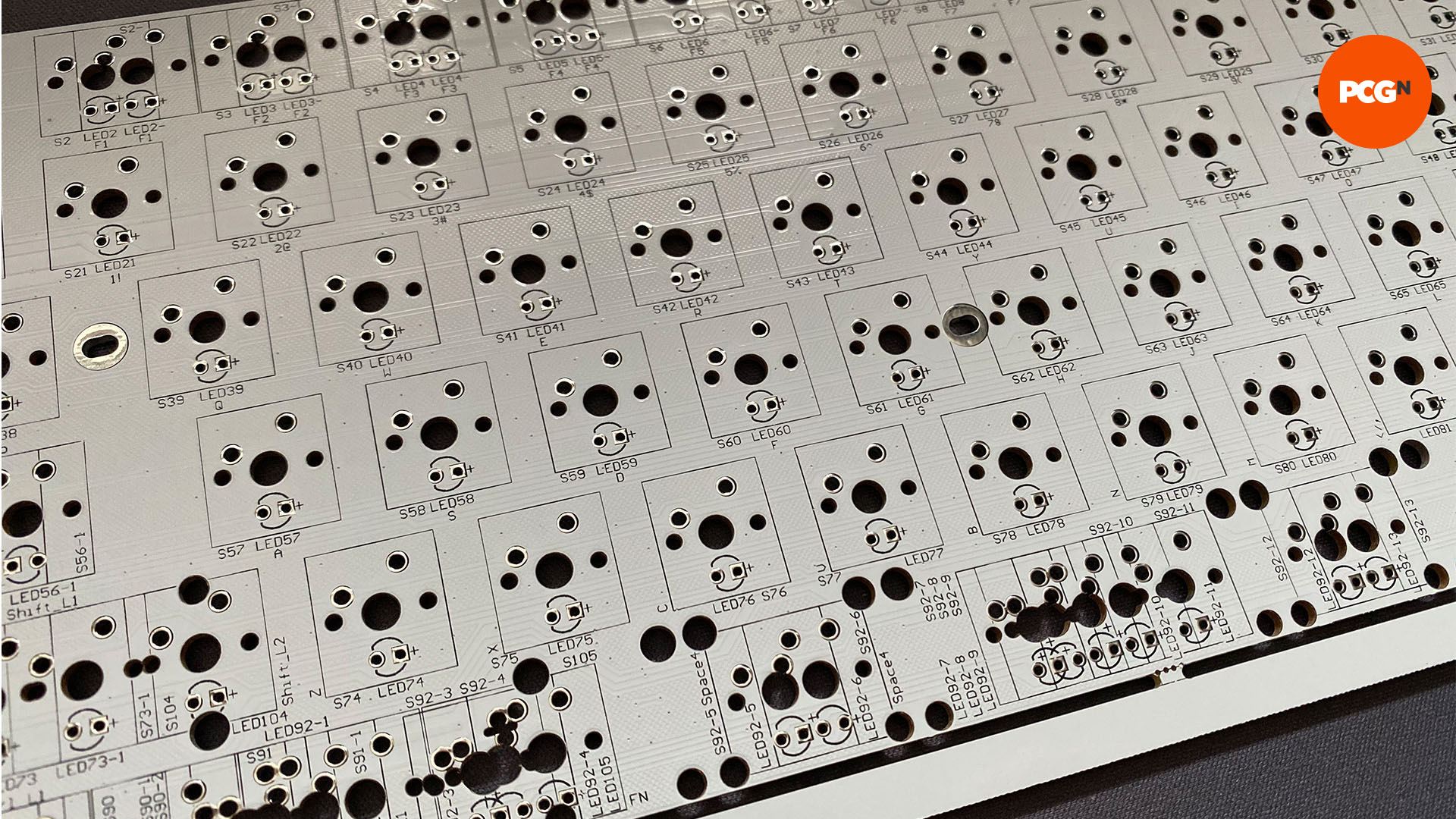

Next on our shopping list is the custom keyboard PCB, which is there to take the input from your switches and turn it into something that your computer can understand. Although you can get cases and switchplates that fit a variety of PCBs – and vice versa – PCBs generally come with the case and plate, forming a full kit that you only then need to source stabilizers, switches, and keycaps to complete. If you’re buying separately, you can expect to pay upwards of $25, with some of the most premium PCBs costing double that.

Most PCBs, or at least the majority of models designed outside Japan and China, are programmable and use an open-source keyboard firmware called QMK. QMK supports a wide range of embedded microcontrollers that read the switches’ signals as you press them, working out what you’ve pressed for how long, and turning that information into a USB Human Interface Device (HID) signal.

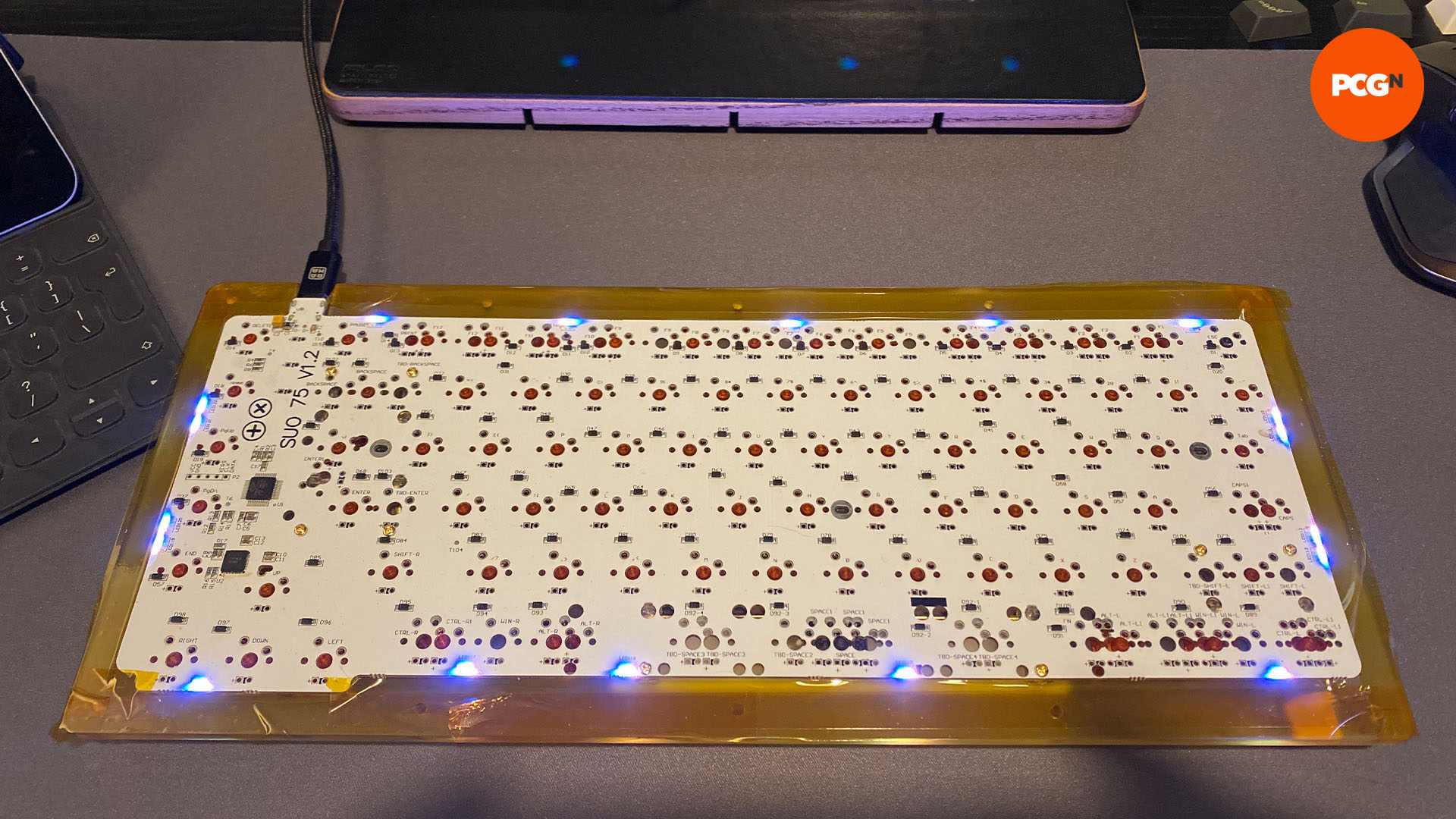

Some PCBs feature integrated lighting, which you can also program via QMK, and activate and modify via key combinations on the board. Some PCBs also feature spots for you to solder in LEDs yourself, including in-switch LEDs that light up underneath the keycaps. There’s a wide array of options here, from a handful of single-color LEDs to full underglow lighting and per-switch RGB.

The last factor to note about PCBs is whether or not you need to solder the switches. The majority of PCBs require soldering, but if you’re not comfortable soldering, there are also hot-swappable PCBs with sockets into which you just push the switch. They’re much easier to assemble but are generally more expensive and can’t support much in the way of layout flexibility.

Which keyboard switch to use

The custom keyboard world has almost completely standardized on Cherry MX-compatible switches, with most boards and keycaps sold today supporting them. Plenty of PC peripheral companies such as Logitech, Razer, and SteelSeries have designed their own mechanical switches but you won’t find them used in the custom market.

However, there is also some niche support for high-end rubber dome switches from a Japanese company called Topre, which are used in pre-built keyboards from the likes of PFU, Leopold and Realforce. There’s also a very small niche for boards that take Alps switches, but considering these switches are no longer made and you need to harvest them from older boards, it’s not a sensible place to start.

The choice of Cherry MX-compatible switches has also exploded, especially in the past year or so. There’s an increasing number of companies other than Cherry making MX switches from all manner of plastics, and with all manner of springs and stems, making Cherry’s own lineup look positively boring. It’s no stretch to say that the custom keyboard community has moved on from Cherry switches almost completely, although, of course, their ready availability makes them a good place to start for beginners.

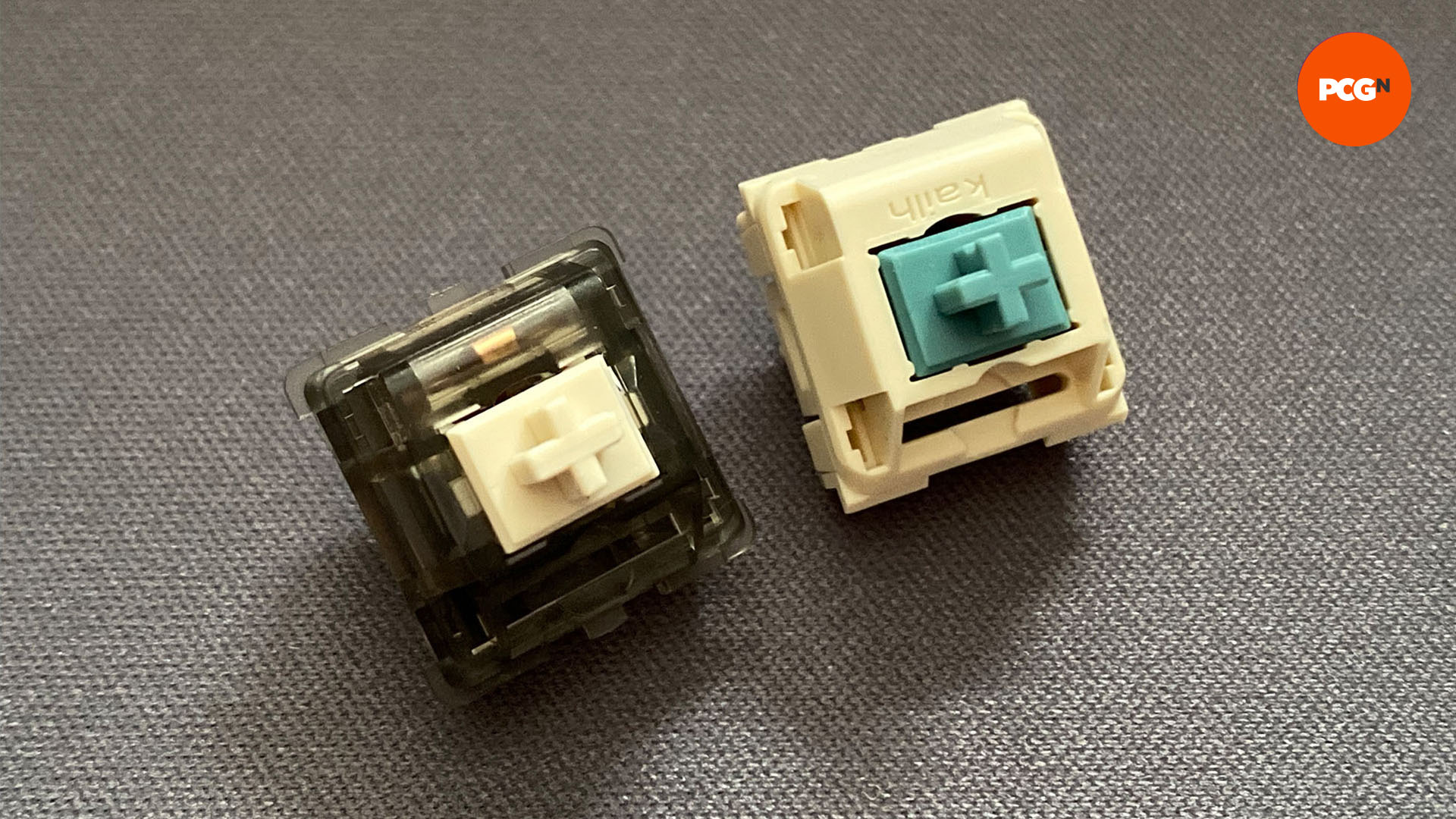

As for types, there are three top-level categories of keyswitch: linear, tactile, and clicky. Linears have no tactile event of any kind in the switch travel, other than when you bottom the switch out. Tactiles have a tactile bump as you push past a point in the switch travel before bottoming out. It’s usually at the point where the switch has activated so you can get the feedback you’ve pressed enough to activate the key without having to bottom out. Clicky switches are tactile in nature too, but the tactile event has an audible click as well.

There are three factors to consider for springs: the amount of force required to actuate the switch, the amount of force required to bottom out, and the progression of the spring rate as you press it. Each of those attributes affects how the switch feels, which is why you can buy switch testers, for trying anywhere from a handful to around 100 different switch types, to see which you prefer.

Switches cost from $0.20 to $1.50 each, depending on desirability. Some switches have attained meme status, usually after being used by a popular build streamer making a board for a high-profile gamer.

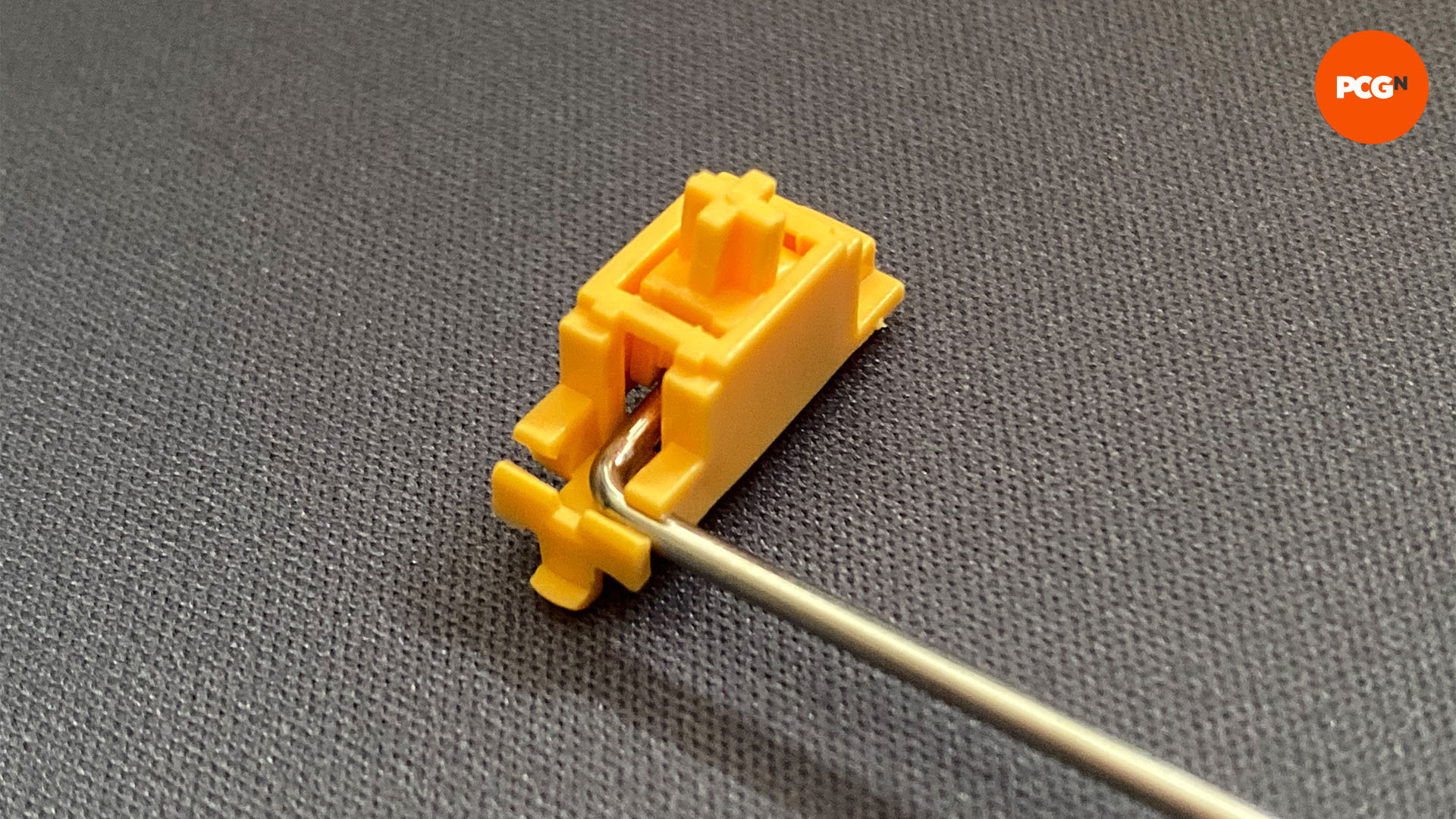

The more hardcore end of the community is also fond of creating Frankenswitches (two examples are pictured above), using parts from two or more switches to create a new one.

It’s very difficult to get a good read on whether certain hybrid switches are actually better than a stock switch, but certain hybrids break through and get enough exposure that you can tell there’s something to them. Holy Pandas are the canonical example, taking the tactile stem from one switch using it with the housing, spring and leaf from another. They are top-tier tactiles when tuned.

Which custom keyboard keycaps to use

Keycaps are the start for most mechanical keyboard enthusiasts. All it takes to customize your typical MX-switched keyboard is to pull off the caps and buy some compatible alternatives. There’s a vast range of colors, shapes, legends (lettering/fonts) and build materials, making it fun to simply mess around with this one aspect of custom keyboards.

Aside from style considerations, the type of plastic and manufacturing process are important factors, as the different types of plastic all wear differently over time and the manufacturing can determine how long the legends on the keycaps stay looking good.

Most notable is the trend for double-shot PBT caps, which use the tougher, more chemically resistant PBT plastic (compared with ABS) and are molded twice (double-shot) such that the legend on the cap isn’t painted on but formed from a second colored plastic that runs the full depth of the cap, so it won’t wear off. Plastics remain the best choice for keycaps due to the light weight and ease of molding, but some designers have tried low-volume manufacture in other materials, including metal.

The final aspect to consider when it comes to keycaps is their profile or shape. The most common are Cherry profile caps, which can be found on the vast majority of pre-built boards, and most keycap group buys are in this profile too. However, Cherry profile caps are relatively short in height (compared with other mechanical keycap profiles) and the bare minimum of plastic is used to make them, so they’re light and thin, which affects how they sound.

Instead, a lot of keyboard makers prefer larger keycap profiles. Keycaps in the MT3 and KAT profiles are my favorite, since they’re higher in profile than Cherry caps and are quite a bit thicker than Cherry-profile sets, so they have a different sound. If you want to see what sort of designs and profiles are out there, take a look at the Keycap Calendar.

Custom keyboard stabilizer options

Most keycaps are attached to the switch underneath by a retaining stem in the center of the cap, which is fine for normal single-width (1U) keys. However, for wider keys, such as a normal-width Backspace (2U), ISO Enter, and especially spacebars (commonly 6U+), a stabilizing system is required. Without a stabilizer, the switch will be very wobbly and, if you press anywhere off-center, there’s a chance the switch won’t activate.

Stabilizers hold up the extremities of the cap on retaining stems that are joined with a wire, so the whole assembly moves up and down with the switch when you press the cap. This helps the longer caps feel stable and lets you press them off-center without any issues.

Stabilizers take two basic forms: plate mount and PCB mount.

Plate mount stabilizers are more common on pre-built boards than customs, but you’ll still find them on some customs too. They aren’t as stable as PCB-mounted ones due to the fairly flimsy clips that are often used to mount them. PCB mount stabilizers tend to be screwed to the PCB from the underside, making for a more secure fit.

Since stabilizers are just a few pieces of plastic and a metal wire, they’re fairly cheap, at around $4 for 2U and $5 for the longer ones for spacebars. That said, some vendors sell sets of stabilizers that the community considers to be of higher quality, which cost more.

Build your custom keyboard

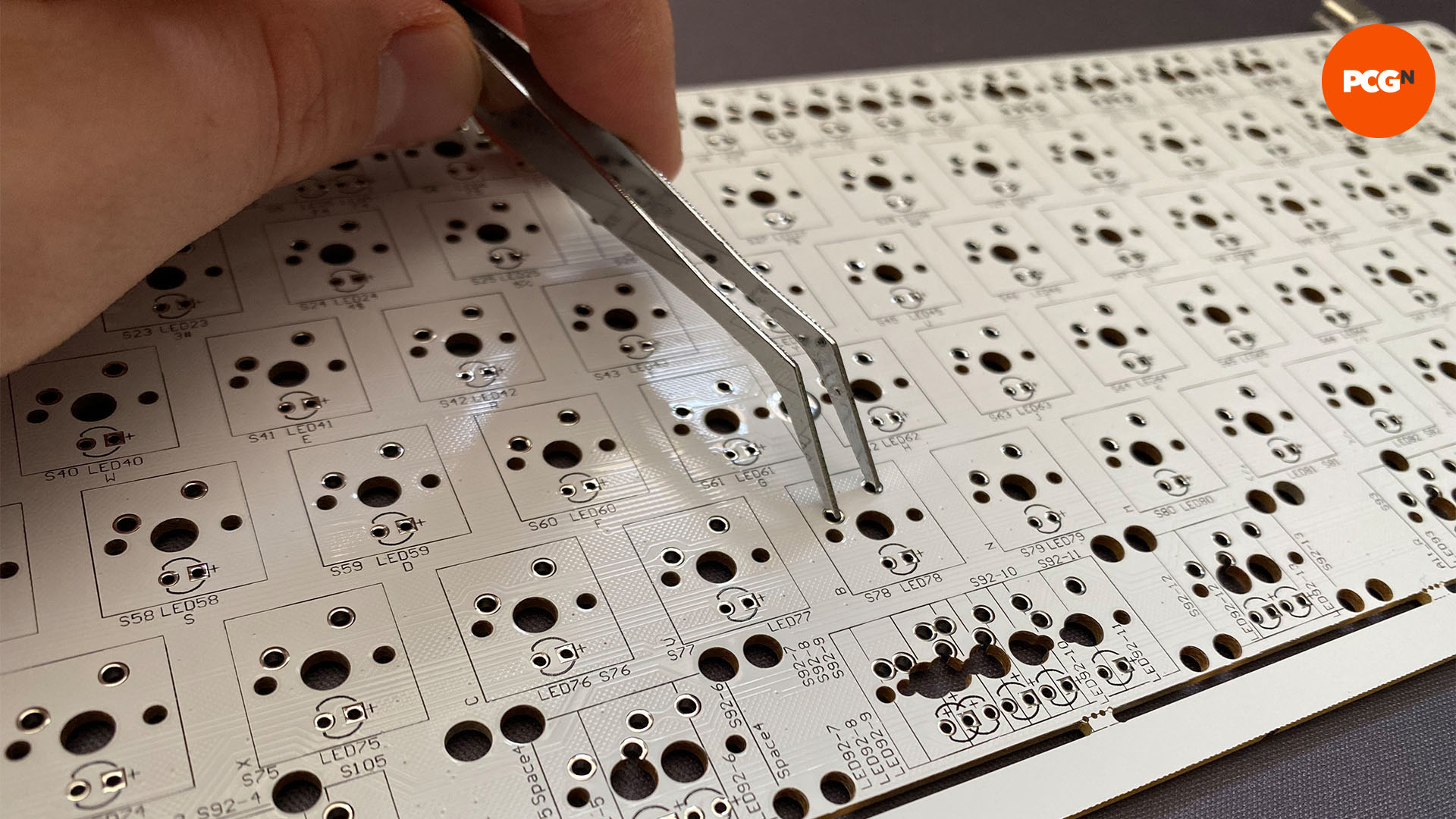

1. Test the custom keyboard PCB

As soldering is hard to reverse, always test your PCB first. Plug it into your PC using a USB cable, then short each switch by touching the two switch pads with a pair of tweezers to see if the switch activates. Using a program such as Switch Hitter will let you also see if the keys that don’t print anything, such as the Shift keys, are also working properly. It happens rarely, but it pays to be careful. The suo PCB by TX Keyboards was my choice for this build. It supports in-switch and underglow LEDs, and is compatible with the HJ75 kit.

2. Fit stabilizers to your custom keyboard

Next, you need to attach the stabilizers to the PCB for all of the keys that need them. On a UK ISO build without a numpad, that’s usually two 2U stabilizers for backspace and enter, and one 6.25U stabilizer for the space bar, but double-check the layout you want to build to be sure. Push your stabilizers into the right mounting holes on the board and screw them to the PCB through the bottom with the provided screws.

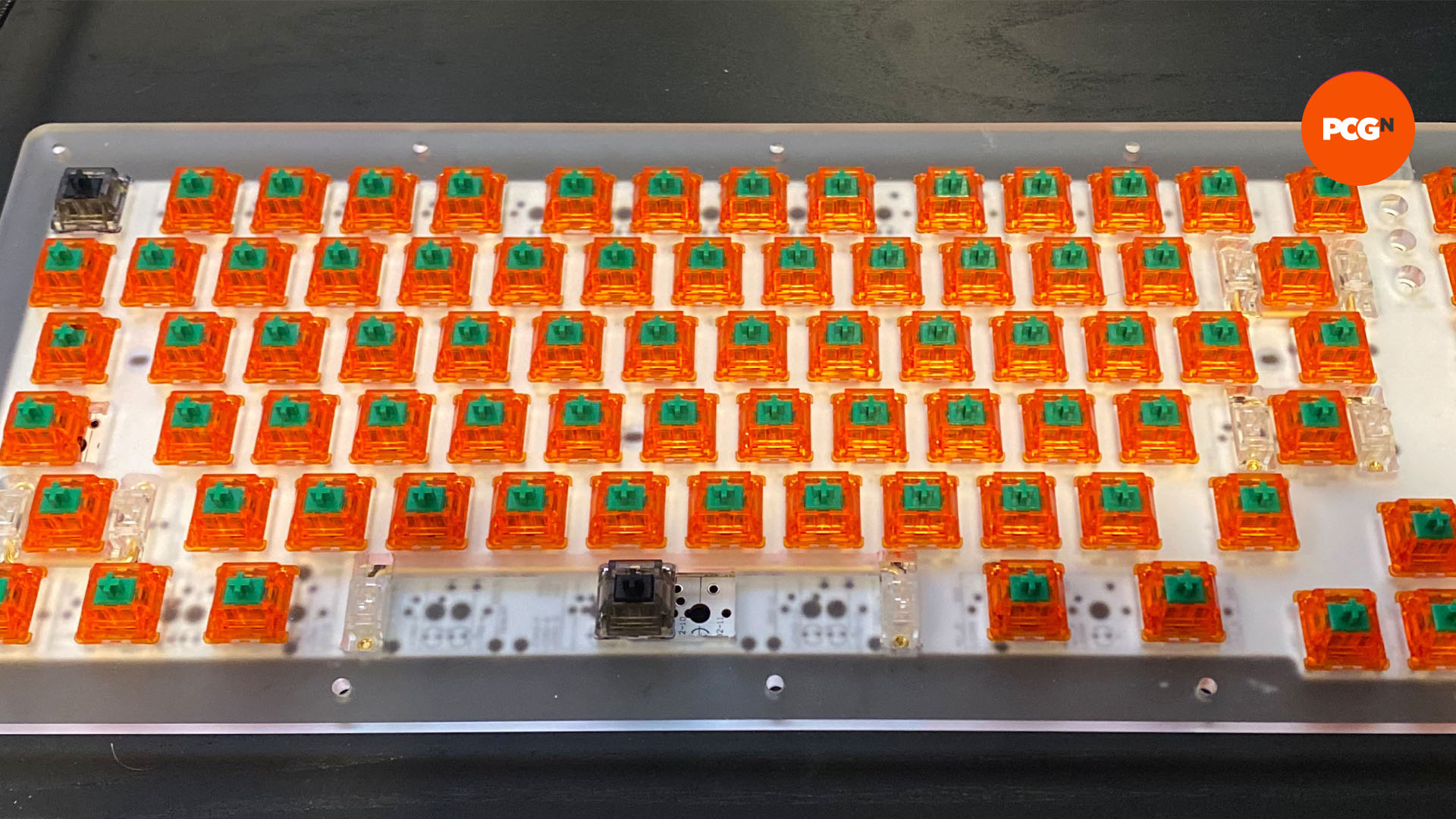

3. Mount your switches on the plate and PCB

The next step is getting all of the switches into the switch plate and pushed into the PCB. Some plates are tight due to the fine machining tolerances, so don’t be afraid to apply a fair amount of pressure, to make sure your switch is securely planted. Make sure the metal legs on each switch are straight before you push them, to minimize the chance of bending them.

Start with the corner switches and a few in the middle, to ensure the plate and PCB are aligned and nicely anchored. This should mean the rest of the switches slide into place easily, reducing the chance of any pinch points. You can choose to solder those initial switches, if you’re comfortable they’re perfectly in position.

Something to look out for when fitting the switches is that mounting points may be ambiguous on plates or PCBs that support different layouts. In such situations, the trick is to fit the required keycaps onto the offending switch and its neighbors and use those as a guide on where exactly to affix the switch. This scenario is especially common on the bottom row where it’s most common for people to tinker with the space bar size and key layout.

When you have all of your switches in place and you’re happy that they’re snugly in place, lift up the whole assembly and eyeball that everything is lined up perfectly, and that all of the switch legs are through their holes and that none of them is bent. Making sure switches are flush to the plate and against the PCB is the most important job when building your board.

For this build I chose the TX Keyboards HJ75 case and switchplate kit, which is a 75 percent size layout and includes the aluminum top, and several clear acrylic plates. I also used C3 Tangerine linear switches lubed with Krytox 205 Grade 0 grease.

4. Solder your custom keyboard PCB

The next step is to solder all of the switches to the PCB. There are just two pins per switch so there’s very little to be done other than work your way across the board, taking your time until you’ve soldered each switch. Double and triple check you’ve done them all, since it’s surprisingly easy to miss one.

After you think you’ve got them all, test your PCB again. With all the switches installed, this is a much easier process than before – just plug it in and press each bare switch and make sure it registers.

5. Assemble your custom keyboard case and fit keycaps

Every board is different here because of the variation in potential mounting options, but the basic idea is to get the switch plate retained to the top case first, before assembling the rest of the case.

Some cases only have a single piece and the PCB screws into it with nothing else to do; others are more intricate with top and bottom pieces, gaskets to lay in the right place for isolation and damping, and some have outboard USB ports that you have to mount separately, that connect to the main PCB with a small connector.

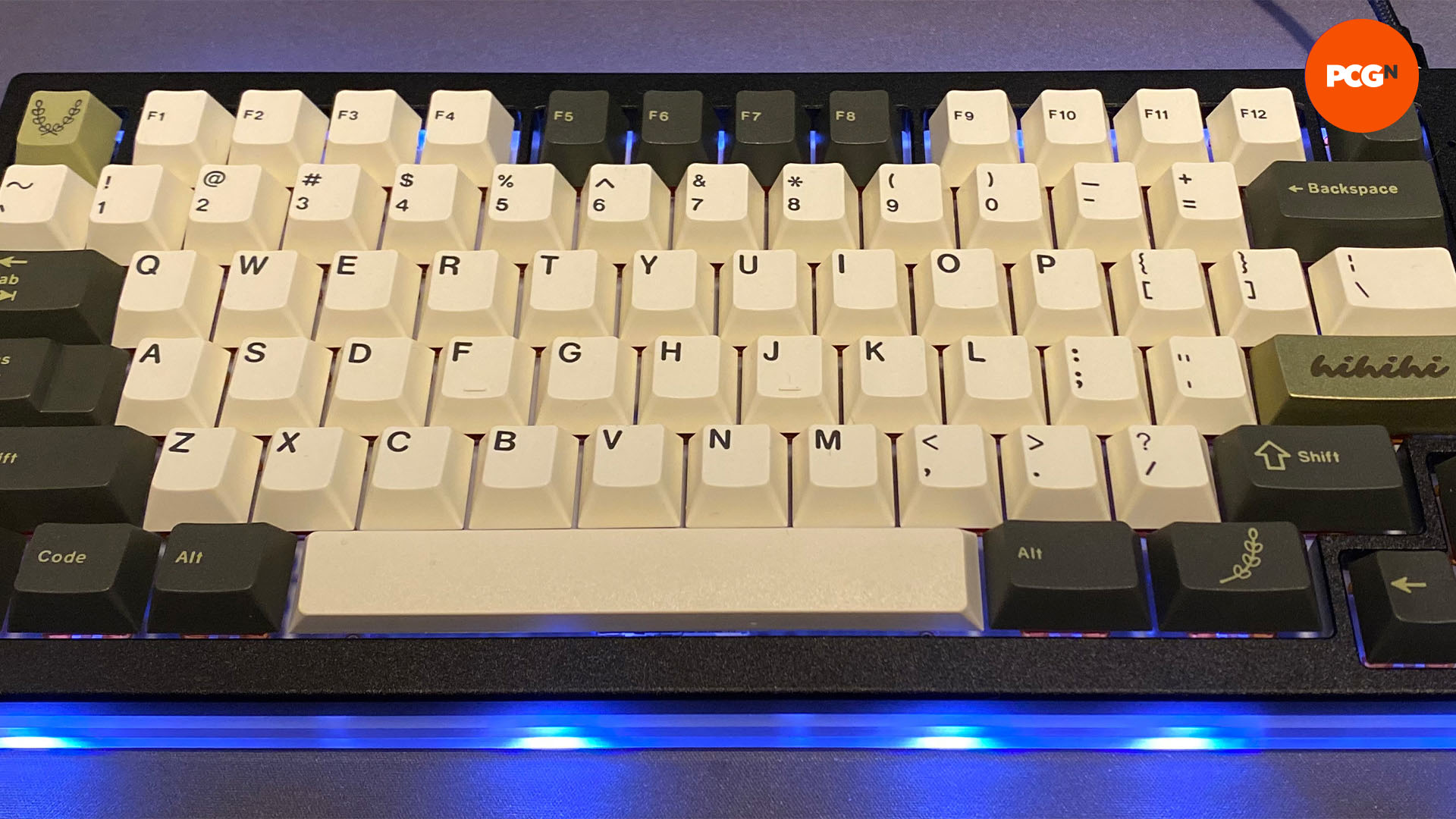

Follow the instructions for the case and other parts that you have and just proceed with caution. Now is also the time to add your keycaps, and for this build, I used GMK Olive keycaps and a metal RAMA Works enter key.

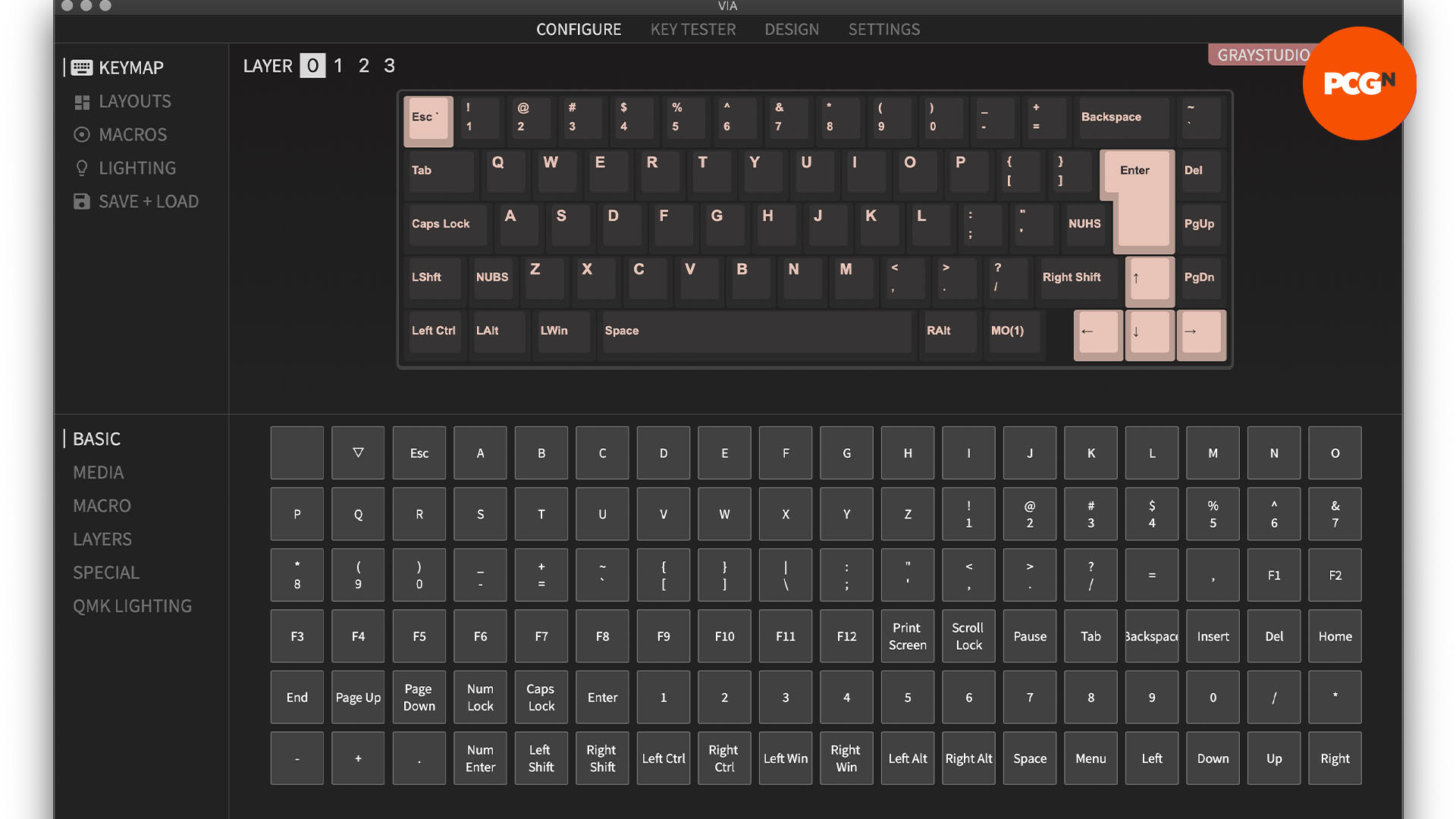

6. Program your custom keyboard

Most custom keyboards have a PCB that supports the QMK firmware. QMK is a highly flexible system that allows for almost endless remapping and configuration of your board. There’s an online QMK configurator that lets you remap your board and generate the new firmware file to flash the PCB once you’ve set it up, and the QMK documentation site has loads of useful guidance on how to get started flashing and programming your board.

If you’re lucky, your board might also have a QMK-based firmware that supports a great configuration tool called VIA that requires no extra flashing to remap your layout. Not all QMK-compatible boards support VIA, so head to the VIA website and take a look at the board and PCB list to see if the one you’re interested in is supported. New boards are being added to VIA regularly, so even if your particular board isn’t on the list today it might be soon enough.

7. Your custom keyboard is done

There’s so much variation in builds that it’s impossible to show you examples of every possible combination of ideas. However, almost every board you’ll find online will come with an associated guide or thread somewhere that explains the build process, or you’ll find that one of the major keyboard streamers has built one on Twitch or YouTube and you can watch how they did it.

That’s a wrap for our keyboard-building guide, and we hope you enjoy assembling and using a board that’s been specified to your exact requirements. Having built almost two dozen custom keyboards over the year, it’s fair to say I’m hooked. It’s a deep rabbit hole of a hobby, but the ability to put together a unique keyboard that you’ve designed and tuned is a big draw. Just beware that you’ll never only build one.

If you’ve decided that the DIY route isn’t for you, make sure you also check out our guide to the best gaming keyboard, where we run you through all the best pre-built options we’ve reviewed. Several of the big names in keyboards are also now starting to integrate DIY features into some of their designs, such as the hot-swappable switches on the new Razer BlackWidow 4 75%, and Glorious’ range of bare bones kits.