If League of Legends is Blu-Ray, then Heroes of Newerth is HD-DVD. Once, one couldn’t be mentioned without reference to the other. But today, in the comment threads where the relative merits of LoL and Valve’s Dota 2 are picked over at length, HoN is rarely mentioned at all.

S2 Games ultimately lost the race for Dota’s audience. But by any other yardstick, Heroes of Newerth is a success that needs no qualification.

Consider: the 15 million installs. The two and a half million monthly active users, and the 700,000 who log in every day. In a list DFC Intelligence and Xfire published in 2012, League of Legends was declared Most Played PC Game in the World – but it was HoN that took fourth place.

The consequence of all this is that there’s no need for a softly-softly approach when I go to see S2 and their new game in California. What’s there to tiptoe around? S2 have a future. HoN’s growth has seen the developers more than double their staff in the last year, and allowed their designers to re-embark on a project they’d previously been forced to abandon. This project, they tell me, will see them capitalise not only on their capital, but also their intimate understanding of Dota-likes. It’ll lift the back-breaking burden of knowledge MOBAs routinely plant on players’ shoulders, and tackle toxicity at its root, in game design – even if that means cutting back some the genre’s key mechanics.

The project is called Strife, and S2 say it will be the first-ever second-generation MOBA. We’ll get to what that means in a minute.

CEO Marc DeForest occupies the best seat in a swish hotel room with a view over the Golden Gate Bridge and, beyond, San Francisco, where Heroes of Newerth’s art team is based. When he talks business, which he does in the voice of a clean-cut Steve Buscemi, he tends to draw metaphors in the air with skinny fingers. Right now, two parallel digits represent separate line items in an invisible ledger. In a moment, each of his hands will become a development team.

S2 isn’t Marc’s first company. A self-described “serial entrepreneur”, he sold his ISP business before the dot com bubble burst and pulled the majority of his money out of bonds early enough to watch the recent market crash from a safe distance. He’s owned a classic car manufacturing plant, a plastic injection molding firm, and several restaurants. While he protests he’s seen as many failures as he has successes, it was his nerve and, one suspects, optimism that saw S2 through a tough first decade.

No, S2 isn’t Marc’s first company – but it’s evidently his favourite. If his introductory speech isn’t up to scratch, he says, we’re to blame the 25 to 30 games of HoN he played over the weekend.

The speech is about MOBAs, naturally enough, and the “maturation process” Marc anticipates they’ll undergo over the next few years. It’s a process that S2 hope to kickstart themselves later this year with Strife – “the first second-generation MOBA that exists”. So what’s one of those, then?

“Here is the first game, the only game that sits in the [MOBA] market that is somebody’s second attempt at making a game in this genre,” explains Marc.

“We’ve learned from watching other [developers]. We’ve learned from people who tried these kinds of games and left these kinds of games, and how they reacted to them. And it’s through being a student of the genre and paying close attention and then applying everything that we’ve learned – that should give us a significant advantage [with Strife].”

S2 were students of their genre when they made Heroes of Newerth, too – but they were copying perhaps too diligently from the blackboard. In transposing the mod that had enthralled them for commercial consumption, none of the team dared to lay a finger on Dota’s design – for fear of smudging its unmistakable fingerprint.

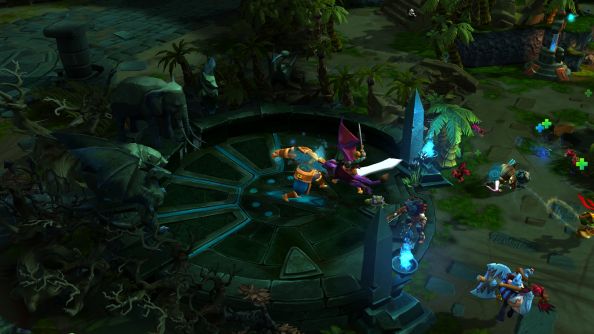

“Clean sheet design” is the phrase I hear underlined with verbal emphasis more than once during the two days I spend with S2 – though you wouldn’t know it to first look at Strife. Its isometric arena is spanned by three cobbled creep highways, and populated by 10 colourful characters – each controlled by a player with access to small array of abilities and a much larger catalogue of items. It turns out that even when the developers tell themselves to question everything, plenty stays the same. They like MOBAs, after all.

Squint a bit, though, and you’ll notice that the map is slightly smaller than HoN’s, leading to earlier teamfights and less trudging. That the flow of those lanes is sometimes violently redirected by hulking AI monsters, directed by players. And that each of those characters is trailed by an eager Pokemon. Sorry: pet – a colourful bundle of extra abilities, bobbing about in battle.

There are only a handful of pets to memorise, and that line of thinking extends to Strife’s roster of Heroes. Right now, the game is home to less than 20 playable characters. A few more are planned for its closed beta in the Autumn, but S2 have set themselves a stript cap they’ll soon hit at their current rate of one new character a month.

The implications are enormous and immediate. LoL, Dota 2 and HoN each feature more than 100 champions, and sooner or later it dawns on every new players that they must learn not only the skillset of the hero they’ve taken a fancy to, but also the the faces and skillsets of every other character in the game. And should they choose to dig into another MOBA, God forbid, they’ll find their vast knowledge made redundant by a mass of similar, yet totally unrecognisable, opponents and spells.

By plumping for a smaller, more varied catalogue of characters, S2 have dramatically reduced the burden of knowledge lumbered on new players. They’ve removed a barrier to entry made of heavy oak and replaced it with balsa wood. And it turns out that’s just the beginning.

I play my first game of Strife in that same hotel room, darkened now, surrounded by European journalists. Connection problems abound, though, and my in-game teammates are all bots. Being bots, they won’t listen to me. Invariably, when I am in one lane, they are in another.

I content myself playing about in the surprisingly accessible item shop – due to be made more accessible by a ‘Recommended Items’ feature before release – and spend 20 minutes muddling reasonably successfully through the early game, last-hitting creeps for cash, until I notice the ginormous ape rampaging down the middle lane towards me.

I calmly make a note in the pad next to me. ‘NEW FEATURE: GINORMOUS APE’.

When I turn back to the game, I find my botmates rushing to defend our central mid-lane tower – now a dull grey, signifying the temporary disablement bestowed on it by the chimp’s attacks. It quickly transpires that when the beast hits a tower, or a hero, or a creep, it does so with its head – and so our android opponents are here too, flanking their monster movie companion, clearing his path to our most vulnerable structures before he caves his own skull in.

Within a minute, the ape has entirely redirected the flow of the game. His name is Krytos, and he does this at least two or three times a match.

Players will stumble across Krytos chained up in one of the many eddies on Strife’s map, guarded by an AI boss that an organised team can defeat relatively early in the game. But as any MOBA player knows, teamwork comes with its own, alliterative shadow: toxicity. Formerly the preserve of biologists and Britney Spears, the word is now well-coined in reference to the damaging behavioural problems that plague the genre. While there’s no doubt that the interdependence Dota and its disciples ask of teammates is responsible for its incredible highs, it’s also turned its arenas into petri dishes for new forms of human hostility.

Both Riot and Valve have made staggering commitments to improving player behaviour. But S2 reason that there’s only so much in-house psychologists can do without digging into the design of their games.

“We realised we can’t fix the human race,” says Marc. “What we can do is look at the things that make people behave poorly and say, ‘What can we do proactively to deal with those situations?’. Because everybody currently in the space right now is currently dealing with this reactively.”

S2 do have reactive systems in place in Strife, but their strongest anti-toxicity measures are mechanical changes. Recognising that MOBA matches are economically-driven, S2 have made a tectonic gold-gathering tweak – the repercussions of which will be felt in every game.

“Most of the controversy and the bantering and the bickering happens within a team,” says S2’s director of monetization, Pu Liu. “And that’s because it’s very hard for a team to decide who should be getting the majority of the resources. I think I’m a better player; obviously you’re going to think you’re a better player and your Hero is more important.”

As such, S2 have tempered the all-or-nothing nature of last-hitting. In Strife, a killed creep will relinquish only half of its worth in gold to its slayer; the remaining 50% will be divvied between the team as a whole.

“Not only is that splitting the gold up so it doesn’t feel like the solo is getting double the resources that everyone else is,” explains Pu, “it’s actually encouraging everyone else to have their best interest in the solo’s success – so they’re more likely to gank and be more generally supportive.”

What’s more, better-performing players will reward their opponents with more gold when slain, driving players away from exploiting ‘feeders’ and minimising frustration among their teammates.

In fact, S2 have made hundreds of granular choices on a design level to minimise that frustration.

“The opportunities to make mistakes that are so game-breaking that people call you out on them are much fewer in Strife,” says Pu. “We wanted to design a game from the ground up so that items are more adaptable to more heroes, and heroes are more adaptable and more divergent in their strategies and viabilities. So that’s it not like, ‘If you make this decision on this hero, you’re a bad player’. It’s how you chose to be effective that game.”

The payoff? “There’s a lot less right and wrong choices, and a lot more customisation in playstyle choices.”

“When you look at it [Strife], it’s very familiar,” concludes Mark. “If you’re a MOBA player, you can look at it and think, ‘I think I’m going to have an idea of how to play this’. But then there’s so many intangibles, some of them subconscious while you’re playing this game, and so many decisions we made and analysed, that we just feel people are going to pick up this game, give it a try, and they’re going to find themselves going back, and going back, and going back.”

In yet another hotel room with a view across San Francisco Bay, Marc DeForest is picking his words carefully. I’ve just asked him how he felt when Valve, the Bellevue behemoth, declared their intentions for Dota’s audience. I’ve asked him whether he was scared.

“Did I think, ‘Could our company potential evaporate because of this?’,” he muses. “Well yeah, you have to think that the worst case scenario you could paint for that is bad. But Dota 2’s been out for a while, and we survived that onslaught. We managed to grow our player base in that onslaught. The question I ask myself, as opposed to just worrying, ‘Oh my gosh, this is scary,’ is to say: ‘How many players would we have if there wasn’t Dota 2?’

“You know what I worry about? I worry about things I can control.”

In 2007, Blu-Ray sales overtook HD-DVD; a year later, Toshiba shut down their HD-DVD operation altogether. But then, Toshiba didn’t have the nerve nor the optimism of a Marc DeForest. And they didn’t have a Strife.