Ion Maiden is a shooter like the ones they used to make. In fact, as I burst through a window at 100mph, gun pointed at a city being brought to its knees, I do a double take: for a split-second I think I am back inside Duke Nukem 3D’s iconic first level, it’s uncanny.

Ion Maiden is not a replication of the games from the ‘90s so much as it is a game from the ‘90s. Sorta. It is being developed in the original Build engine, which powered shooter classics including Blood, Shadow Warrior, and yes, Duke Nukem 3D. It is also being published by 3D Realms, who made some of those games – it seems to be in good hands, then.

Want more retro games? Here are the PC classics still worth playing.

Almost everything you remember from that era of first-person shooters can be found in Ion Maiden. You move terrifically fast, search for key cards to unlock doors, and gobble up armour shards and health packs that are laid out in neat lines across the floor. Even the protagonist’s portrait sits in the corner of the screen grimacing and getting bloodier as she takes damage.

It is a wonderful return to retro form which benefits from being outfitted with the kind of modern comforts that modders have given the likes of Doom in recent years – among them, mouse look, kickable gore, and smooth frame rates. The only aspect that is missing is the sleaze – throwing money at pole dancers, for instance – which is no bad thing.

All of this feels like a rush of comforting nostalgia, then, but there is one particular moment that wins me over.

“You are still missing 30 secrets in this area…”

The message flashes up on the screen as I reach the first exit room in Ion Maiden’s preview campaign. A surge of electricity courses through my brain, reconnecting synaptic pathways that have lain dormant since 1999. The ellipsis nags at me. Secrets, you say – missing? I am not the kind of player who can shrug off such a wide chasm of missed content. What treasures have I left behind? How many pixelated vistas have not had the chance to grace my eyes? Are assassins still squashed into tight spaces expecting me to walk by so they can jump out and pump me full of lead? Those poor fools.

Frozen on the spot, staring at the exit elevator only inches away, I consider the shooting galleries I spent the past 20 minutes rushing through, bloodying up the furniture along the way. I thought my rampage across Neo DC had been thorough. I threw bombs at buses, slaughtered dozens of cyborgs dressed in gross red hoods, I even tried to jump into a pipe full of green toxic waste for two whole minutes. A ghostly architecture begins to haunt my mind: jilted corridors, abandoned elevators, forsaken staircases, all of them crying out to me from the dark. Don’t worry, pals, you might be out of sight but you are not out of mind – I am coming for you.

I turn back. There are hundreds of nondescript walls out there I have yet to drag myself against while hammering the ‘E’ key. I came here to clear this place of invaders, but that is done now – now Iam the invader.

In the pursuit of those 30 secrets I flip the entire first level around like a Rubik’s Cube. What was once forgettable decoration on the walls and floors now looks temptingly like a facade to be ripped open and peered into. Vent covers are shot off and crawled through, scaffolding becomes thin platforms to jump up and across, pressure switches hidden in the floor are exposed by the grating sound of the doors they open in the distance. I have to decipher the language that developers Voidpoint have created to subtly broadcast the location of Ion Maiden’s secrets. Tune into the right frequency and, voila, there are signposts everywhere.

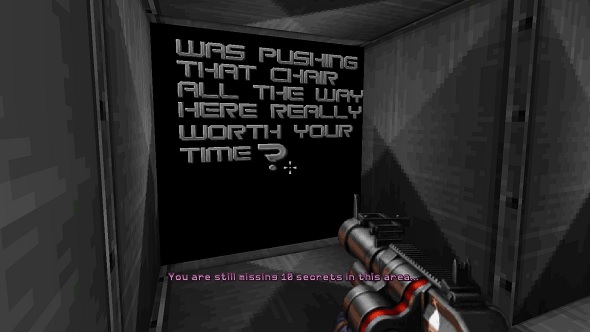

My favourite of the secret seeker’s tools are the office chairs that can be pushed around and used to reach elevated platforms and passages. In one office, a message scrawled angrily onto a piece of lined paper reads, “DON’T YOU DARE STEAL MY CHAIR!” Sorry, guy, but I am taking it: I steal the seat and roll it over to the opposite wall where I use it to jump up to a vent in which a suit of armour waits. Out of spite, I then steer the chair all the way to the elevator, where we ride down the entire length of the building, just so I can reach yet another ventilation space, this time in the exit room. There’s no armour this time but there is another note. It reads: “Was pushing that chair all the way here really worth your time?”

Ion Maiden’s subversive attitude is afforded partly by the outrageousness of the decade that it is in thrall to. Videogames were brash, rude, and dangerous back then – GTA’s criminals, Lara Croft’s sex appeal, Mortal Kombat’s violence. Ion Maiden plays up to the perceived edginess of those games. Its other winning ingredient is level design that aims to be as complex as possible within the limitations of its polygon count – interlocking spaces, maze-like topography, scalable verticality. This is how first-person shooters entertained us before theatrical set-pieces, achievement hunting, and realism became the pillars of the genre.

It is all there in that first level. Centered on a single office building, it gives you a Die Hard situation: one hero versus many terrorists. My first approach is epitomised by a single moment spent accelerating across the carpet of an executive lounge firing a submachine gun at anything that moves. But by hunting for those secrets I become the John McClane of this scenario. I have to learn the ins-and-outs of that architecture, find new ways to infiltrate it, past locked doors, even pulling a book to reveal a room behind a fireplace. This allows me to be more experimental with how I complete my mission – I sneak through vents, dropping behind guards to the tune of a shotgun blast in the back. Not only that, it reveals the jokes the developers have hidden for people to find, exposing a playfulness that the po-faced military shooters of today lack.

So, was it worth pushing that chair from its place behind a desk to the basement, with the only reward being a snarky message from the developers? Yes, it was. And I encourage you to go find it too.