There’s a thing scientists do when they’re trying to figure out what elements are contained in a star. It’s called spectrum analysis. By measuring the frequencies of lights radiating from a celestial orb, analysts produce a chart made up of just a few thin colours.

Related: the best indie games money can buy.

Square Enix Collective creator Phil Elliott looks at triple-A gaming that way: covering just a few thin colours along the spectrum of human emotion.

“We’re really, really good at racing games, or sports games, or action games,” he says. “And every so often there’ll be something that breaks out and encompasses more feelings, like a Life is Strange or Shadow of the Colossus. But still, when you compare it to TV or film or literature, there’s a lot more we can do.

“When you compare that with the indie space, there are so many more colours there. It’s so much more vibrant.”

It’s unusual to hear a figure from a major publisher talk this way. But then Square Enix Collective is an unusual initiative: a no-strings-attached offer to promote and consult on games from outside the company, in the hope that Squeenix can fold a little of that colour – the diversity of experience and emotion currently found only in indie games – back into AAA.

Here’s how it works: on the 20th of every month, Elliott and his team open up submissions to developers for two days. In that time they give studios feedback on their pitches, and pick four projects to post to the Collective website.

Then, over a course of a 28 day campaign, Squeenix put the chosen games in front of new eyes – the Deus Ex and Hitman fans following the publisher on Twitter and Facebook. They aim to get between 20-30,000 people looking at a pitch, and ask: “Would you back this game through crowdfunding?”.

The publishers require developers to put together a weekly production schedule. They ask for a weighty design document, and have a senior producer or game director work through it with a fine tooth comb. They advise on screenshots and subtitles.

But you’ll notice nobody’s made any money at this stage.

“We don’t touch the game code. We’re not collecting the funds, so all we’re doing is trying to use our experience as a publisher to work with developers,” explains Elliott. “There’s no requirement to work with us on anything else.”

If both sides are up for it though, though, Square Enix will throw their weight behind those developers on Kickstarter. They take 5% of the of the net crowdfunding cash raised, to help cover costs. But even then, there’s nothing tying the developer down.

“The first game that we supported on Kickstarter is a game called Moon Hunters,” says Elliott. “We would have loved to publish that game. We think that team, Kitfox, has got real talent and we can’t wait to see what they do in the future. But they really wanted to self-publish.”

It’s a remarkably hands-off operation – so much so that from the outside it can appear as if nothing of substance is going on. But among the seven or eight campaigns Collective support a year, Square Enix are finding some of that colour they’ve been missing.

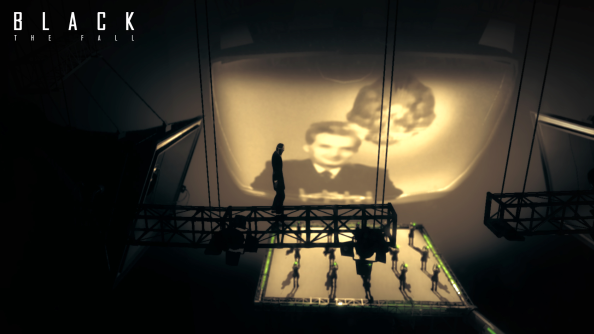

This year will see existential space adventure The Turing Test and communist dystopian sidescroller Black The Fall join the Collective publishing slate. Ghostly point-and-click Goetia is already released and, if Steam user reviews are anything to go by, exceptionally good. Last month, meanwhile, saw the Kickstarter success of Fear Effect Sedna, rebooting an Eidos series that had lain dormant since the PlayStation.

So the Collective is working out for Square Enix. The question is whether the scheme is yielding results for the developers – now over 100 of them – who have so far put in the prep and paperwork.

They’re certainly getting their games before an audience, beginning to build communities and gauging interest – often cited as one of the bigger benefits of Kickstarter. But more tangibly, Collective has helped the developers under its wing raise more than $1,000,000 in total since its launch in 2014.

It’s not charity. But Elliott insists Collective isn’t really about building revenue.

“We’re not using indie money to fund the next Final Fantasy game or anything like that,” he laughs. “The point of this is to support newcomers. We think that conveyer belt into the industry is as important as the stuff that’s big now.”

You’ve probably noticed: on an average week Steam is drowning in new releases, as the technical barrier and costs of development come down. That’s good news for us, and curators help bring the best to the top. But many first-time studios see their games fleetingly grace the front page before sinking into obscurity.

“There are maybe 20,000 micro-studios now, and if they all shipped once every three years, that’s still way too many,” reckons Elliott. “So we know that we can’t help everyone, we know that not everyone is going to succeed. The games have still got to be good. But what really worries me is the real gems out there that, because discovery is hard, just never make it.”

Back when he ran the trade site GamesIndustry.biz, Elliott visited the warehouse studio where a bunch of indie developers sat huddled around a sidescrolling stunt game called Joe Danger.

“I’ll be honest,” he remembers. “I thought the game was nice [but] I was more of a Trials fan.”

That studio, of course, was the nascent Hello Games.

“I never expected No Man’s Sky but, my God,” says Elliott. “How much interest and excitement has that got? If Sony had never supported them in the early days, maybe they would never have been able to make it. There’s a chance they wouldn’t.”