This is the first part in a new series looking at pivotal games in the history of PC gaming. Whether due to their scope, amibition, sheer quality or otherwise, these are some of the titles that have defined the medium.

Robert B. Marks is the author of Diablo: Demonsbane, The EverQuest Companion, and Garwulf’s Corner. His newest book, An Odyssey into Video Games and Pop Culture, is coming out on October 15th, and is available for pre-order in print.

Videogames are not a young medium.

It’s easy to think that they are – the home computer is only around 36 years old, and the present golden age of videogames, with slick triple-A titles and a wildly imaginative indie scene, was made possible by the last 20 years of technology. But while they are arguably the youngest medium of modern entertainment, the history of videogames stretches back at least three generations and counting – the earliest known game-playing computer, Nimatron, was unveiled in 1940 at the New York World’s Fair, and even that date may be supplanted by an earlier one as new evidence becomes available.

Over the next few weeks, this series is going to look at some of the titles that were crucial steps in videogames maturing into the medium they are today. It’s going to place each title into the context of the 76-year history of the videogame, talk about what the games did, why they were important, and the impact they had, not just on players but on the medium as a whole. It is not a comprehensive list, nor could it be. However, each game has an importance that extends far beyond its contemporaries, not just in how it succeeds, but sometimes even in how it fails. Some of the titles were influential, some were groundbreaking, and many were great.

But, in the end, if one considers what might be the greatest PC game of all time, there is one outstanding candidate.

Once upon a time, there was a company called MicroProse, which made computer games. It started off in 1982 specializing in simulations, and flourished during the 1980s and early 1990s. However, by the end of the ‘90s it was struggling, and MicroProse ceased to exist in 2001. Of the many games it created, all but one franchise is forgotten – a game series that has become such an institution that it would be impossible to think of the world of videogames without it: Civilization.

Strategy games are arguably the oldest form of electronic gaming, dating back to Nimatron in 1940. Throughout the 1950s, computer strategy games were used by the Rand Corporation for military purposes, and while the university-centric world of computer gaming in the 1960s appears to be light on strategy titles, by 1972 a strategy war game named Invasion appeared on the Magnavox Odyssey, the first videogame console, and home computers were playing them since at least SSI’s Computer Bismarck in 1980. By 1990, there was not a single type of strategic or tactical warfare that had not been simulated in a computer strategy game in some capacity – with one exception.

Nobody had simulated the entirety of human history.

Even in board games, the scope was limited. Hartland Trefoil and Avalon Hill had released a game titled Civilization, designed by Francis Tresham, in 1980. But this Civilization was a resource gathering game that limited itself to the ancient world – the Medieval era and beyond were left untouched.

Sid Meier was not the first to conceive of a computer game spanning the whole of human history, but he was the first to implement one. There were two other projects, both of which failed to get off the ground. One was an attempt by Dan Bunten to adapt the Avalon Hill game to the computer in the mid-1980s, but he couldn’t get the support he needed to fund the project. The second was by Don Daglow, who began programming a game in 1987, but was lured away from it by an offer to become an executive at Brøderbund – as a result, the project was dropped and never picked back up.

Like so many games, Civilization was not developed in a vacuum. Sid Meier and his collaborator, Bruce Shelley, had been inspired by games such as Risk and SimCity, and Meier later told Gamasutra that the game had started as an adaptation of Risk, with the technology and historical elements added throughout development, as well as a shift from real-time strategy to turn-based gameplay.

Perhaps one of the great ironies of the development and success of Civilization is that it happened in spite of MicroProse. Sid Meier had been a founder of the company in 1982, but by 1990 he had been bought out and was working as a contractor. The new vice president of development who had replaced Meier didn’t receive any bonuses for Meier’s titles, and starved Civilization of resources, art assets, and marketing muscle. The company president, Bill Stealey, was an ex-fighter pilot who didn’t really understand or care for games that weren’t rooted in the military – his approach to the project resembled a reluctant faith that it would not crash and burn. In many ways, when Civilization shipped in 1991, it had become a pet project that MicroProse tolerated more than supported.

Upon release, Civilization was the definition of a grass roots success, and one of MicroProse’s most successful games. It became one of the origins of the ‘just one more turn’ phenomenon, with players reporting losing entire nights to the game, only realizing how much time had passed when their alarm clocks went off in the morning.

What made Civilization special was that, for the first time in the entire medium, it offered an experience that could only be found in a videogame. Every other videogame genre, from adventure to space simulator, could be otherwise replicated in some capacity, from watching a movie to joining the Air Force to playing a board game to reading a book. But Civilization put players at the head of an empire for the entirety of history, making them a key decision maker in international politics and trade as entire ages dawned and passed into memory. Even the best of general world history books could not offer that. In doing so, Sid Meier’s Civilization became the title that justified videogames and set them apart as a medium.

All of which makes Civilization all the more remarkable when one considers how flawed it was.

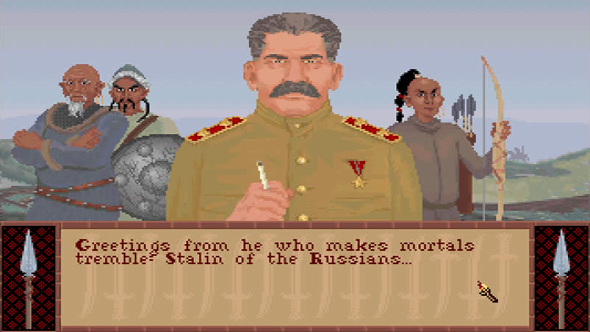

And it was deeply flawed, despite what our rose-tinted glasses may have us believe. Although the basic graphics could be hand waved away as a result of the computer technology of 1991 and MicroProse’s withholding of assets during development, many of the design decisions could not. The diplomacy model was rudimentary at best, lacking the basic ability to demand that an AI player remove its units from your territory, thus necessitating a declaration of war just to deal with a wayward settler or caravel sitting on a needed resource square.

While the units had attack and defence values, they had no hit points, resulting in bizarre combat results such as a Bronze Age-era phalanx sinking a modern battleship or shooting down a warplane. Republics and Democracies would impose peace treaties on the player regardless of how aggressive the enemy civilization had been or how many previous treaties it had broken. An error in coding transformed India’s Mahatma Gandhi – famous for his successful non-violent protest strategy that wrestled India away from the British Empire – into a late-game warmonger, more likely to launch nukes than any other AI player.

And, due to a miscalculation of psychology, players failed to notice an entire aspect of gameplay: Sid Meier had built the game so that the player’s civilization would rise, decline, and then rise again triumphant out of its own ashes. However, as soon as the civilization began to decline, players would reload an earlier saved game and prevent it.

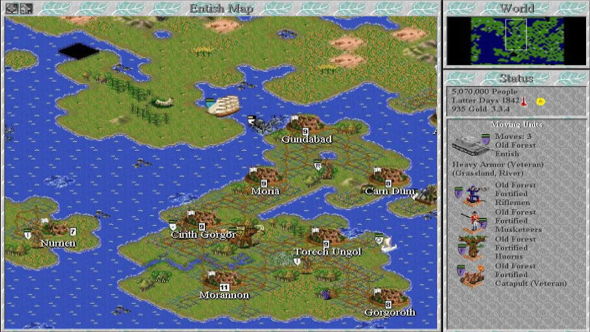

It was the sequel, Civilization II (1996), designed by Brian Reynolds, Douglas Kaufman, and Jeff Briggs, that cemented the franchise’s place in videogame history. Civilization II improved on the strengths of its predecessor, and removed all of its weaknesses. The diplomatic model was expanded, allowing for the enforcement of national borders without requiring a war every time an AI unit had wandered into the player’s territory, and adding a reputation mechanic which lent weight to a player’s foreign policy actions and made other nations less inclined to trust or negotiate if past treaties had been violated. Units received firepower and hit point stats, removing the disbelief-inducing combat results from the previous game. And a map editor was included, allowing players to use the game engine to create and play scenarios.

Civilization II even managed to next-level what a player could accomplish through cheating. By the Civilization II: Multiplayer Gold edition, the game had a cheat menu that, among other things, allowed one to reveal the entire map, set all the players to AIs, and watch them fight it out. The game became a true simulator, with the computer running through an entire alternate world history as the player pressed the enter key and watched.

Civilization’s impact was both nuanced and massive. It wasn’t long before the game had imitators, with its use of tech trees and empire building being replicated in games such as Master of Orion (MicroProse, 1993), Galactic Civilizations (a game released in 1993 for OS/2 by Stardock), and Sid Meier’s own Master of Magic (MicroProse, 1994), which recast the Civilization formula into a fantasy world bearing a marked resemblance to Magic: The Gathering. Ensemble’s Age of Empires (published in 1997 by Microsoft) brought the concept of historical empire-building to the real-time strategy genre, and Creative Assembly’s Total War series (2000-present) would incorporate many of the gameplay elements of Civilization into its turn-based sections.

But while Civilization had imitators, it had surprisingly few direct competitors. In 1999, Activision produced and published Civilization: Call to Power, which attempted to expand the game concept on a number of levels, increasing the timeframe into the far future of the year 3000 and allowing for the colonization of space and the oceans. This resulted in a legal battle between MicroProse and Activision, wherein Activision was allowed to make additional Call to Power games (they released only one in 2000), but not to use the name Civilization. MicroProse’s direct response was Civilization II: Test of Time (1999), a remake of Civilization II that also offered an extended game that continued on to the colonization of Alpha Centauri, as well as science fiction and fantasy campaigns. The game also inspired an open source project, FreeCiv, which began in 1996 as an attempt to see if it was possible to create a multiplayer Civilization-style game with a client-server model.

The true successor to Civilization and Civilization II, however, would come from the man who created it in the first place. After founding his company, Firaxis, in 1996, Sid Meier acquired the rights to make more Civilization titles as MicroProse fell, and in 2001 released Civilization III – a game that went back to basics in many ways (gone was the expansion of the timeframe, as well as space and ocean colonization), but also expanded the depth of the gameplay with cultural borders and new victory conditions. Meier served as a director and producer, but not the lead designer. This would be followed by Civilization IV (2005), V (2010), and now VI (2016).

Today, the Civilization series stands as a monolith in the world of videogames. By giving the player the whole of human history to experience, it became a game with unparalleled scope and possibilities, and justified its medium in the process.