Take a look at Project Eternity, potential fantasy RPG and Kickstarter concept of the hour. At the time of writing, it has long since reached its minimum target and nears $1.8 million in funding, where stretch goals promise development of a new playable race, class, and companion. At $2 mil there’ll be a player house; at $2.2 mil, Linux support. Stretch goals beyond $2.4 mil are TBA, but momentum is such that developer Obsidian couldn’t be blamed for tentatively writing them up this afternoon.

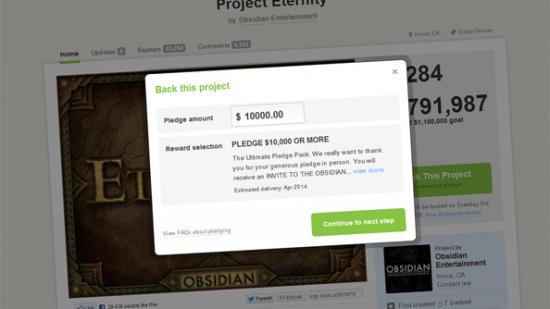

Yet in the world of groundswell publishing, not all pledges are equal. Amongst the 43,089 backers Project Eternity has amassed to date, less than 100 are responsible for 8% of the development budget. Of that near-$1.8 million total, these 93 backers have together offered $141,000 – in some cases, more than $10,000 each.

There’s no publicity to be had. Unlike the similarly epochal Humble Indie Bundle, there’s no top ten contributors page. What’s more, a comprehensive Gamasutra survey reveals no evidence of nepotism – big spenders rarely know the creators of the projects they are so crucial in funding. Who are these men and women, then, who spend thousands of dollars when they could spend 30 or less?

Sam Posten is a New Jersey software engineer. He pledged $1,000 to inXile, and in return will become an NPC in Wasteland 2.

“Had any other game offered this I wouldn’t have been interested,” says Posten. “It was specifically for Wasteland alone. Others since have offered similar rewards and I haven’t kicked in over $35 on those.”

For Posten, Wasteland 2’s campaign was a perfect storm – the first of its kind, and featuring the sequel to his favourite game. Five months on, he has no regrets about his pledge: “I have every bit of confidence that Brian and his team are going to build a spiritual successor that both rocks as a modern game and rekindles the love and nostalgia I have for the original.”

Two things, then, convinced Sam to part with so much of his cash: the reward itself, and goodwill towards the project’s team, the individuals themselves – both fuelled by nostalgia.

The same two motivations convinced Steve Dengler to spend $5,000 on Project Eternity. Dengler made his fortune with online currency exchange site www.xe.com, and now uses his acquired wealth to fund game projects – most notably those of Double Fine. Without him, there would be no Psychonauts on Mac, and no Costume Quest or Stacking on PC. When we catch up with him, though, he’s been looking into the specifics of designing the Dracogen Tavern, his in-game reward for pledging to Obsidian’s project.

“I can put real life people at tables in the tavern,” he laughs. “That’s cool. And in The Banner Saga, I’m a god in the game. They actually made me a deity.”

For Dengler, Kickstarter rewards allow him to take part in the creation of new worlds. “Sure, in many cases you can become a backer for $20 or $30 but you don’t get the cool perks. I’ve been a gamer for 30 years now, and it’s one thing to play games but another to have a hand in shaping the culture, the landscape, the events or the background of the game.”

Although Dengler is now lucky enough to know some of his favourite developers personally – as a self-described “super-fan” – his fondness for them and his willingness to fund projects still seems tied to a love of their past work.

“I’ve been very fortunate with my circumstances, so when I see a project that’s being made by a studio I really like, or people I really, really like – I like Brian Fargo, I like Tim Schafer, I like Chris Avellone, I know these guys – it’s fun to be able to take those resources and give back.

“When you look at Project Eternity, if you look at the number of gaming hours that somebody like Chris Avellone has given me over the years, I’d still say [$5,000 is] pretty cheap. If you went through and divided my contribution by all of those hours – probably thousands of hours – it’s not that much money actually.”

As CEO and sole staffer of Dracogen, Dengler takes into consideration the same qualities: “If you can show me there’s a reasonable prospect of getting my money back, and I like the people, and I like the work, and it speaks to me personally – if all those stars align [I’ll get involved].”

Dengler’s experience on the other side of campaigns – where, no matter the names attached, doubt sets in at the eve of launch – means he likes to pledge early. “It’s nice to come in at the beginning and give it a little boost, so that in the first little while that number’s moving up at a fair clip,” he says.

“And if you get the uber supporters, the ones that take the higher level stuff, it really gets the inertia for the project going. It makes the lower levels get more involved, because they think, ‘Hang on, this is something that could actually end up being made’.”