On an early Sunday morning in April 1999, game designer Chris Sawyer was perched in his living room command center, a collection of ‘90s tech, browsing forums online. In late March, the inaugural RollerCoaster Tycoon had landed on shelves in North America dripping with Sawyer’s contagious love of theme parks, and something appeared to have gone seriously wrong.

In the forums, players were saying the game had somehow lost their progress and sent them back to square one in the game’s scenarios, which advance sequentially like levels. After years of careful work, the game appeared to have self-destructed for mysterious reasons. But Sawyer had a hunch: last night, daylight savings time had taken effect.

Perhaps it was more than a coincidence. Within a couple of hours, he had uncovered the connection. The adjusted time-stamps on the save game files, there to safeguard against tampering or corruption, weren’t matching up. “Embarrassingly, it was a blatant bug on my part,” Sawyer says. “Or was it?”

The system call he used should have yielded the time in UTC, unchanged by daylight savings, creating no problem. “Only for some reason,” he says, “it did change!” He quickly coded a patch and later a utility to fix the save game files.

The greater irony was that RollerCoaster Tycoon otherwise stood as a monument to what a single person can accomplish in programming. Written almost entirely in assembly code (like Sawyer’s previous Transport Tycoon), RollerCoaster Tycoon and its sequel squeezed and re-squeezed the processors of the time to simulate rides, economies, and up to thousands of visitors and their states of mind. Churning through so many numbers in real-time without hitching demanded a lean, uncompromising approach and not the slower, more user-friendly C family of languages. And in ultra-lean assembly, where letters stand in for ones and zeroes, one speaks directly to the processor.

It’s an extremely difficult language to learn and has been going out of style since the development of Fortran in the 1950s. In his early days, Sawyer released a handful of z80-coded games in the mid-1980s and went on to become a stalwart at converting Amiga games to DOS, including the classic Elite II.

Handsome and sprightly, he then went into business for himself and created Transport Tycoon while holding onto its rights, a habit that has provided him with a steady source of income. Some of it went into traveling Europe and the US to ride roller coasters at places like Cedar Point in Ohio. He’s now ridden more than 700 coasters. His favorite, Taron at Phantasialand in Germany, looks like something out of a Tycoon game.

Sawyer gravitated to x86 assembly naturally, appreciating its clean presentation and lightning-fast compiling, and when he set out to make RollerCoaster Tycoon, he rigged two PCs: a fast one for coding and a slower one for testing. (The game’s system requirements later called for an Intel Pentium 90mhz with at least 16 megabytes of RAM.) Also sat atop his command post were a dot matrix printer (he believes), a fax machine, a pocket guide to x86 assembly code, and a 500ish-page desktop reference. This was enough for him; although the full manuals run into thousands of pages, he’d memorised most of what he needed.

“I’d been programming in x86 for so long I rarely needed to look things up,” he says.

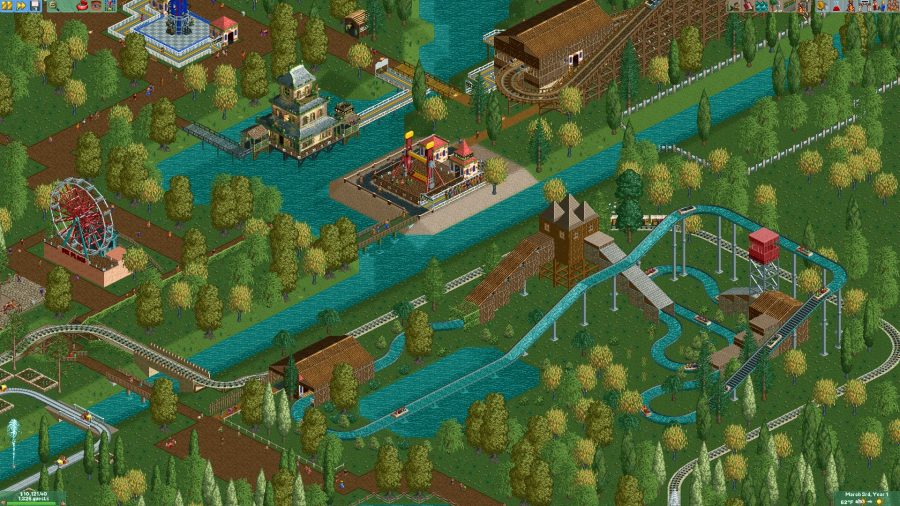

The earliest game resembled Transport Tycoon but with roller coasters, and its graphic artist Simon Foster created a more flexible and photorealistic system so the coasters would look the part. Much of the initial design process was freeform and inspired by a few obvious predecessors: Will Wright, Peter Molyneux, Sid Meier. But most of all, Sawyer had to prioritise performance. New features meant a greater burden on the slow, guinea pig PC, and while some of them could be lanced from the code, others had to stay.

Pathfinding was one of these, and it became the biggest headache. “It’s easy to program a route-searching algorithm that works perfectly,” Sawyer says, “but it’s of no use if it stalls the game for seconds or minutes at a time when it needs to make a decision.”

He chipped away at the algorithms, stranding many little men and women in the bushes and down the wrong decorative path. “I’d visited quite a few large theme parks in the US by then and managed to get lost in some of them myself,” he says. “So I thought it was probably right that the guests in RollerCoaster Tycoon also struggled […] if the park layout was poorly designed.”

Once the game had evolved from ramshackle wish list to an SVGA temple to theme parks, Sawyer spread it around to friends, neighbours, and the neighbours’ children, who responded very positively. Publisher Hasbro arranged for professional bug-hunting playtesters, and Sawyer did his own endless probing. And despite the daylight savings time hiccup, RollerCoaster Tycoon went on to be the top-selling PC game of 1999.

For the sequel, Sawyer added to the original code base, drawing closer to his ultimate vision. “I still love that game and everything about it,” he told Eurogamer in 2016. Sawyer kept going with assembly, using it almost exclusively to code Chris Sawyer’s Locomotion in 2004, his most ambitious game to date and also his last major desktop title. He’s since stepped back from game development and licensed the rights for the new RollerCoaster Tycoon games to Atari – efforts that have never come close to the success of the first two.

Sawyer just doesn’t get along with the industry as it is right now, though he appreciates the recent resurgence in management sims. There’s little need for an assembly coder these days (as he agrees), and working as a lone wolf is harder than ever. “I also feel I’ve now created all the games I wanted to create,” he says, including mobile versions of his classic games, “and working on someone else’s game designs just doesn’t excite me.”