Our Verdict

Koei does an unrivalled job representing the complex history and characters of the period, but the lack of variety in the experience combined with a steep price tag makes it hard to endorse without reservation.

The Three Kingdoms is a complex period of history, both in terms of how it’s been romanticised over thousands of years, transforming many of its leading figures into cultural folk heroes, or simply in terms of the sheer number of said characters in play during that time, each as varied as their own ambition for China.

How do you best represent the conflicts of a period in which every warlord and their grandmother was vying to be Emperor? Since its inception in 1985, Koei Tecmo’s ‘historical simulation series’ Romance of the Three Kingdoms has been doing just that, using its grand strategy format to let players step into the shoes of a warlord from the period.

Up front: I’ve never played a game from the series before, but as someone interested in the Three Kingdoms and familiar with grand strategy, I was excited to play with fresh eyes.

Romance of the Three Kingdoms XIV offers players a variety of historical scenarios, from the Yellow Turban Rebellion, to the Warlord period, to the conflict between the kingdoms of Wei, Han, and Wu. You can pick from a number of characters during each, but you can also create your own, describing their lineage, their defining traits, battle tactics, and even writing them a bio if you want to. You can then insert them into a scenario and either play as them, or as another potential opponent or ally. This adds a good deal of customisation to scenarios, which to some extent offsets the fact that this is currently XIV’s only game mode (there’s no multiplayer, either).

Your objective in each scenario is invariably to unify China, governing the land but also defeating your opponents through turn-based battle and diplomacy. The diplomacy system isn’t extensive, so most of your expansion will occur in the manner to which grand strategy fans are accustomed: through force.

When battle does inevitably occur, the decisive factors boil down to formation, tactics, terrain, and supply lines. If an opponent cuts off your supply line, separating your influence trail from your city, your forces will start to decline. I really like this; it means you have to watch your flanks, and necessitates the use of fortifications like earthen walls or arrow towers.

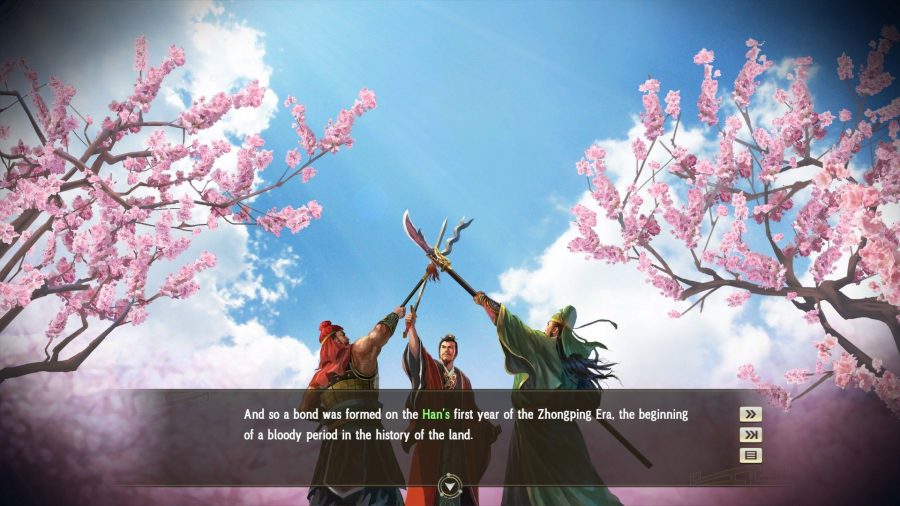

Just like most things in XIV, there is an initial appearance of simplicity, which through scale can escalate into complication – usually the signature of a good wargame. I also love the ways in which characters and their battle tactics synergise – it neatly emphasises the iconic relationships of the period, such as the oath between Liu Bei, Guan Yu, and Zhang Fei, strengthening historical ties with game mechanics.

I also really enjoyed the narrative beats. Once certain criteria are met, you can watch a cutscene of a historical event – this, coupled with the narrative setup for each scenario, really helps to teach players the history of the period. It’s also a refreshingly different approach, to say, Total War: Three Kingdoms. Let it never be said that I don’t enjoy Total War’s relatively muted approach to character, but XIV’s figures feel larger than life, more similar to the positions they hold as cultural folk legends – the unique character portraits (of which there are a generous 150) also go a long way in creating that impression.

But XIV can also feel a little boring at times, either when just watching armies painting in the blanks as they conquer territory – which they can sometimes do pretty nonsensically – or in terms of its objectives. The fact that you never have a goal beyond ‘unify China’ is kind of anachronistic in terms of what I think a scenario is supposed to represent: that ambitions and objectives change over time.

Total War: Three Kingdoms represents this perfectly in its most recent expansion, Mandate of Heaven, introducing time-based start positions which depict the journey of characters through various objectives and events. XIV does offer a series of ‘plots’ which can be undertaken to weaken an enemy, such as Hidden Poison, which affects development and public order in a targeted area, or Unattended Home, which causes a viceroy or governor to abandon their faction.

But while these actions go some way to represent the ambition and betrayal that was part of the atmosphere of the period, they don’t do enough to differentiate the personal ambitions of characters in the form of goals, whether through mini-objectives or quests. Characters and ambitions are what make the Three Kingdoms period so dynamic and special, and XIV could really have done more to represent make its characters come alive – not just in their wonderful portraits and cutscenes, but in actual gameplay.

City and area management also don’t take too much work as you simply allot a recruitment overseer to accumulate soldiers in a city and then area overseers to develop either agriculture, commerce, or barracks, improving supplies, income, or soldiers respectively. There is also your administration which confers buffs based upon which characters hold which positions.

Romance of the Three Kingdoms XIV is a fun mixture of history and grand strategy, and long time fans of the series will enjoy some of the new additions, but it also feels limited to me. It has depth, escalates in complexity, and has a cool character creation system that could perhaps teach Total War a thing or two. But it’s a very samey experience releasing at a time when many of the leading lights of grand strategy have learned to add variety to the old map-painting trudge, and its current price tag of $65 (£49.99) may give pause, especially to any budding Three Kingdoms enthusiasts looking to build on their experience in Total War.