Sid Meier’s Starships is a game of galactic control. Your mission is to claim over 51% of the galaxy’s territory or, if you’re more conquest minded, to take your opponents’ home worlds.

But it wouldn’t be called Starships without the glorious celestial vehicles that make up your fleet. Made up of individually upgradeable components, your fleet evolves over a campaign into a wing of vessels bristling with cannons, fighter bays, and torpedo tubes.

Starships is a tightly designed turn-based strategy game that’s very, very satisfying to play.

This is a much more broad stroke strategy game than Meier’s other offerings. You aren’t going to get lost in the tech trees of Civilisation or Beyond Earth in Starships. Nor will you spend time being diplomatic: galactic control comes at the end of a gun.

When you boot up Starships the galaxy is spread out before you as a web of interconnected planets. This galactic map is only half of the game, though. Every time you jump your ship into orbit around a foreign planet the game zooms into the space surrounding the planet and gives you direct control over the ships in your fleet, letting you command them in battle against your enemies.

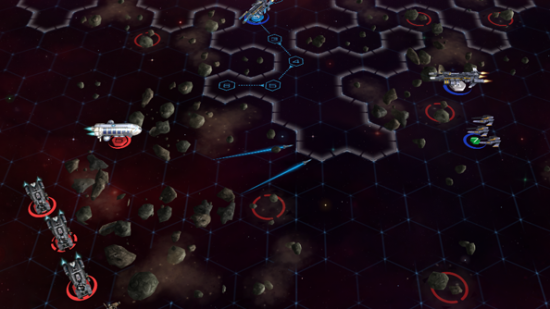

Combat on the hex-based battlefields of Starships is turn-based and tactical. Your ships can move and act once each turn. That can mean either firing their main guns, launching a wing of fighters, repairing critical damage, or maybe releasing a torpedo.

While not as complex as something like Xcom, the combat in Starships has enough depth to let you play strategically. If you can score a hit on the rear of an enemy ship it will do a lot more damage than at the front, and the closer you get to the enemy, and the less astral debris between you and your target, the more damage you’ll do. Get lucky and you can cause critical damage on enemy ships, disabling particular systems. A well struck torpedo can leave whole fleets with leaking engines, broken hangar bays, and busted laser cannons.

Your ships are made up of upgradeable components – engines, hull plating, sensor arrays, and a clutch of different weapons. You can spend credits to fit a ship with a long-range laser cannon and then upgrade that cannon into a battery of turrets. Over a campaign your ships will begin to bristle with the weapons you’ve picked for them.

One of the wonderful things about Starships is that your upgrades are reflected in the ships’ appearance. Ships start off as small vessels but, as you upgrade their separate components, they expand into dreadnoughts, and, eventually, capital ships.

Your fleet isn’t just for fighting, it’s how you move around the galaxy and interact with other planets, too.

At the start of your turn all the planets in the galaxy generate a potential mission – one might ask you to destroy a defecting scientists’ ship, another might ask you to escort colonists through marauder territory, another might be to escape an asteroid field which changes shape every turn. Success gets you a reward, either resources or a free tech upgrade, and gains you influence with that planet’s government.

One point of influence means 25% of the planet’s resource output goes to you at the end of every turn. Two points, 50%. Three points, 100%. And, at four points, the government opts to join your federation, adding its local space to your territory, getting you closer to that 51% galactic control you’re aiming for.

Once you’ve influence over a planet you can order the construction of resource-generating facilities and new cities; the cities acting as a multiplier to your resource gain. Planetary upgrades are simple, they construct instantly and you don’t need to physically place them, just select them on a menu, keeping your focus squarely on your fleet touring the galaxy.

Meier’s managed to inject a little tactical flourish into fleet movement, too. As your fleet jumps about the galaxy making friends and alienating… aliens it gets more fatigued. A fatigued crew is less effective – doing less damage and receiving more in combat. It’s a neat system because it informs how you structure your turn: do you take on the more dangerous missions first while your crew is fresh, or take them on at the end, spending the credits you’ve earned on easier missions to upgrade your ships’ components?

While Starships is simpler than Firaxis’ other games, and that might disappoint some fans, it’s one of the most accessible 4x games I’ve played. Within two turns of my first campaign I was thinking how to exploit Starships mechanics to maximise the gains I could make each turn.

It may not engage you for as long as Civilisation, absorbing your evenings for years to come, but it’s definitely got its hooks in me. I can’t wait to play a full campaign when Sid Meier’s Starships’ March 12 release date on comes around.