Our Verdict

A compact, confident, bite-sized roguelite with a bit too much emphasis on the ‘lite’.

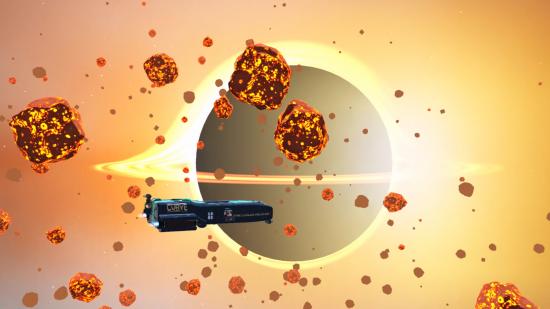

As a bite-sized roguelite, Space Crew is as compact and well tuned as a new captain’s console stuffed with top-of-the-line navigation instruments. After a short few drilling exercises, even rookie cadets will know the difference between their plasma cannons and their shield generators, medical bays and escape pods. Salty space admirals looking to test their strategic mettle, however, might find Space Crew’s charming-but-limited gameplay loop a few crates short of a cargo hold.

I named my first ship The Big Dick Enterprise. Juvenile? Probably, but never let it be said that I shy away from the Freudian implications of hurtling through space in a giant metal oblong. Space Crew’s cosmos is populated by an aggressive, Grey-like alien species called phasmids. They would eventually destroy the BDE, but I took some satisfaction knowing that their first encounter with Terran diplomacy was getting shot at by a cruiser with a dick joke embossed on the side in bold lettering.

The phasmids are your main source of grief in Space Crew. You’ll kick off a mission to deliver cargo, or rescue a stranded astronaut from a doomed station, and eventually be rudely interrupted by some phasmids trying to blast your ship into tiny particles.

These issues arise one after the other on a sort of cascading scale of Bad Things You Need to Deal With before Things Get Worse. It’s a plate-spinner, essentially. Your shields are usually the first thing to go, ticking down from 100 to nothing as you frantically decide how best to divide your primary resource: your crew.

You get six of them, each specialised in their own seat on your bridge. If they’re sitting in that seat, they’ll get access to special, helpful commands. Those shields that are currently getting plasma-battered? Your security officer can restore them in a pinch, or your engineer can divert more power to them, or your captain can fly defensively. Providing, again, that they’re sitting in the right chair.

So, simple right? Just keep everyone in their place, and keep everything ship-shape? Bold of you to assume that. I like your moxie, but I’m afraid you are wrong. Here’s the first problem: there are more stations than there are crewmates. Two extra gun stations, actually, which you’ll need someone to hop in if you want to avoid getting your hull melted off.

Here are some more problems: fires and damaged components, like the oxygen tank that produces the actual air your crew needs to actually breathe. Or the engines, that not only provide mobility and evasiveness, but leak radiation when damaged that slowly chips away at your crew’s health while they glow a disturbing shade of green. Oh, and sometimes phasmids will board your ship and pop in to say hello, with guns, so you’ll need someone to grab a gun of your own and show them the door. You could always get your security officer to open the airlocks, potentially jettisoning a crewmate in the process. But maybe they’re off grabbing a medkit to revive the captain, moving really slow because you turned off gravity to boost weapons, like a giant sausage who’s rubbish at strategy.

And this, at its core, is Space Crew. A series of How? If? But… decisions that nearly always involve making your ship less functional in one area to bolster another. You can slow time and issue commands, and you can pause, but you can’t pause and issue commands. So, there’s always a tangible, twitchy, head vs heart conflict; the urge to stamp out each fire as it appears, pitted against the wisdom that you should probably put your boots on first.

A successful mission gives you research and cash, for unlocking and buying new tech, respectively, and crewmates get new abilities as they level up. The core loop stays the same, though. I do have issues with it, but I’d like to state the obvious, which is this: you’re probably not looking to buy Space Crew in order to review it. Short expeditions of a mission or two at a time seem like both the intended and best way to experience Space Crew. If you’re buying it for this purpose – coffee breaks and stolen moments – I think you’ll have a great time, and at $20/£18, the price is about right.

More like this: The best space games on PC

The same could be said, however, for Into the Breach, FTL, and Slay the Spire, and those games all lend themselves to extended sessions, too. So I don’t think Space Crew quite sticks the landing here. There are plenty of decisions to make during combat, but very few before you encounter any phasmids. You can choose between faster or safer routes across the galaxy, but unless your ship is on fire, the only obstacle to going slowly is your own tolerance for boredom. It makes it feel less like a journey of discovery, more the occasional exciting radar blip.

I also never felt any real attachment to the crew themselves. They’re an element that developer Runner Duck felt important enough to base a narrative trailer on, but these admittedly charming, chibi-style astronauts never felt like people to me, only mannequins with roles. There are no character traits, special quirks, or anything except appearance to separate one captain from the next. You could build a head canon for long-surviving crewmates, chronicling their various daring escapes and victorious missions, but there aren’t enough emergent elements to make these stories feel distinct, or even worth keeping track of.

Related: The best simulation games on PC

For much of the time I spent playing, I couldn’t help thinking about how much an Overcooked-style multiplayer mode would elevate Space Crew to an absolute corker of a party game, putting all the more pressure on your boggle-eyed, confused group as you try to work out how to communicate. As it is, even when the crew’s all accounted for, it’s a somewhat lonely journey through stars that don’t shine all that brightly once you’ve charted them.