When humans colonise Mars, they won’t be the first to land. The robots will already be there – RC rovers and drones packed away with bags of concrete, polymers, metals, electronics, and food in remotely-piloted ships.

Read more: the best strategy games on PC.

Faraway though they are, these synthetic space-travellers won’t be beyond the influence of Earth. In Surviving Mars, the red planet management game from Tropico 5’s Haemimont Games – and perhaps more pertinently, the first Paradox city-builder to follow Cities: Skylines – those vessels will be filled with materials picked by you. They’ll be funded by a space race sponsor of your choosing, and guided by a commander you’ve nominated. This is the first step in a story about struggling for control, over both an unyielding environment and the mental wellbeing of your colonists.

One thing you can control with absolute certainty is your landing site. It’s a choice of trade-offs: a tempting area might host a wealth of easily-accessible resources to help get your colony off the ground, but suffer from a harsher climate that you’ll battle with forever.

“You can go and play where Curiosity landed,” enthuses Haemimont CEO Gabriel Dobrev – though it’s worth emphasising that the studio’s take on Mars is randomly generated. It’s designed to resemble Mars as we know it but remain playable.

“Everybody has a vague idea about what Mars looks like,” notes Dobrev. “And then there’s what Mars actually looks like.”

In the modest beginning, you’ll send out your unmanned rovers to gather resources – the littler, wheeled drones zooming around them, chipping away adorably at rocks – and start producing energy through solar panels.

“Before mankind can come, we need to prepare first,” says Dobrev.

Then, you’ll build refineries to turn the surface of Mars into cement. Happily, structures in Surviving Mars prioritise visual clarity over authenticity: the cement factories physically reach out into the terrain around them with gigantic rollers, flattening the rock with aesthetically-pleasing simplicity. Yet their function is based on real-life research; Haemimont have taught themselves about the technologies that might one day be used to make the planet habitable.

On that subject: you’re going to have to science the shit out of this. Solar panels won’t produce during the cold nights, so over time you’ll build alternate energy options like wind turbines to keep the lights on. You’ll extract water from below, heating it to high temperatures and storing it in towers on the surface. Other industrial machines, when they’re not laid low by dust storms, will take carbon dioxide and split the molecules to provide the colony with oxygen. And then, finally, you’ll be ready for human beings. Whether they’ll be ready for the colony is another matter.

“We’re way too fragile, and there are a number of ways everything can break,” explains Dobrev, as if he were still speaking about the rovers. “If you continually experience outage of oxygen, that’s going to affect your mental health.”

For every individual who lands on your colony, there are bars representing their physical and mental wellbeing. They need oxygen, water, food and proper pressure. And once the basics are sorted, they also need comfort and purpose. It’s crucial to point out: your colony in Surviving Mars isn’t humanity’s last hope, and fuel refineries make return trips to Earth a real possibility. If your people aren’t happy with their environment, they’ll simply sod off back home. Or go insane.

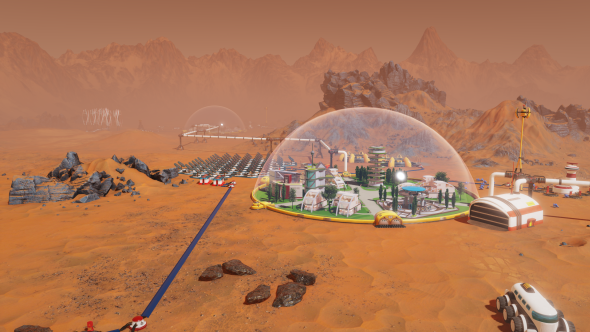

That said, their living conditions can get quite lovely. Haemimont have built Simpson’s Movie style domes for their colonists to inhabit. The retro-futuristic homes inside resemble the high concept houses of the ‘60s, all grass roofs and lots of curves. For inspiration, the studio looked at the optimistic sci-fi of The Jetsons and Futurama – before giving their buildings a practical edge befitting the surface of Mars.

To have a self-sustaining colony, you need children. And in order for your colonists to have children on Mars, they need to be absolutely certain that things are only going to get better. That belief is represented by Morale, which represents whether a particular colonist’s goals are aligned with the colony’s, or whether they’re feeling disillusioned.

“People can turn into renegades and start looking out for their own interests and not those of the colony,” says Dobrev.

Individuals have traits: a given colonist might be, for instance, a hedonist, frail, frugal, and a workaholic. You can cherry-pick the people you want to take to Mars, but also can’t afford to be too picky – you need the numbers. That said, there’s always the option of sticking all the hedonists in one dome, and all the workaholics in another – like some crazy venn society.

“The social part of the game is the last thing that kicks in,” notes Dobrev. “You have this society you can play around with.”

What that society is ultimately for is largely down to you. You’ll have contact with your sponsor back on Earth, who will have goals they’d like you to achieve – a higher population, or a pile of resources to send back home. But that’s not the endgame. Your endgame might be to build multiple bases, or begin growing food on the surface, or to harvest the mass quantities of materials buried underground.

“This is not a game about achieving a particular exit. It’s a sandbox,” says Dobrev. “There is no fixed end. There is no victory screen. What is victory is for you to decide. Play as long as you want – we are simply simulating what’s happening in the colony.”

Despite their penchant for science and simulation, however, it’s clear that Haemimont have been equally inspired by the huge body of science fiction set on Mars. Later in the game, as you discover natural phenomena and begin to decipher them, things can get weird.

As Dobrev eventually admits, for all their reading and research: “We don’t really know what we’re going to find on Mars.”