Here’s a secret about game developers: they’re really into coding. I know – these are the scoops you keep reading for. But more than that, they’re code evangelists. If they had their way, they’d get you into coding too. They wish you understood the satisfaction of a command well executed, or the pride felt for a system that grows beyond its creator’s expectations.

Read more: the finest indie games on PC.

That’s certainly true for Istanbul’s Abyss Gameworks, judging from the situation they’ve engineered for you. In first-person sci-fi game Tartarus, you’re trapped on a mining vessel bound for collision with Neptune – and only reprogramming the ship’s systems will prevent a crash. Yep: only coding can save the day, and for that to happen, you’re going to have to learn a little code.

But how does a developer go about embedding functioning terminals within a first-person game? And how deep down the programming hole should they allow players to go?

Terminal velocity

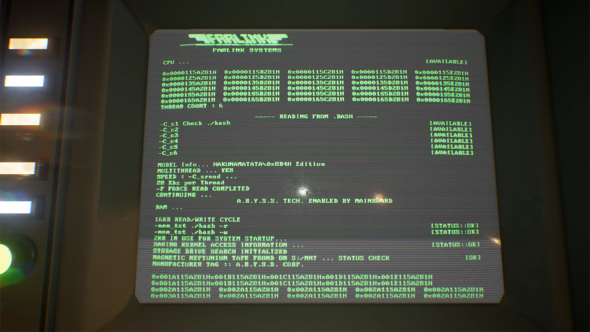

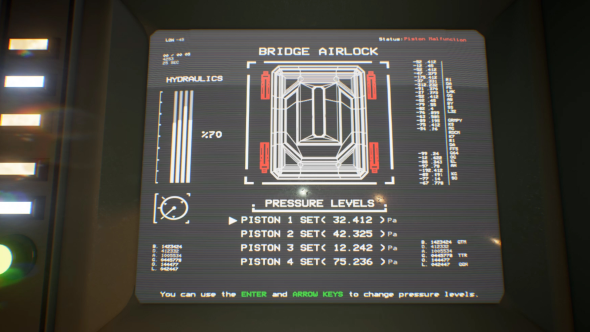

When you find a monitor aboard the MRS TARTARUS 220478, you can activate it with the press of key. The program Abyss have built for terminals boots up, and all other gameplay elements and controls are disabled in the background in aid of performance. The studio have repurposed UMG, the Unreal Engine 4 tool intended for UI design, as a core mechanic.

“It felt like I was actually coding a real operating system,” recalls lead programmer Sertac Ogan.

It isn’t really an OS, but a clever illusion. All the files and directories visible on Tartarus’ terminals are arrays – bundles of data housed together within a single unit in Unreal Engine 4.

“We catch every single user input from the keyboard, parse them to logical components, and process those components,” says Ogan. “After that, the system that we wrote decides which ones are commands and parameters. That is the main trick behind that illusion.”

Each of Abyss’ pre-set commands triggers a special event in a corresponding part of the system. And if the input doesn’t match the commands the terminal is expecting, it’ll flag up an ‘error message’ the studio have designed for just that scenario.

“There are unique mistakes too,” Ogan notes. “You don’t get the same error message everywhere.”

Code within code

In designing their hacking interface, Abyss wanted a realistic but not overly complex system.

“We wanted a system that is easy to use once you understand it,” Ogan explains. “But it can be really hard to understand if you are not familiar to at least some aspects of programming.”

That doesn’t mean that Tartarus is intended for programmers only – just that we’re expected to flail a little bit to begin with. After all, the game’s protagonist Cooper is no programmer either, but a miner caught up in a desperate situation.

“Imagine a person who can’t read, but you’re giving them a book,” says Ogan. “We want that feeling – the feeling of obscurity. So our terminals are your friends but you have to talk to them in their language. You have to read everything. We think we found the right combination between complex and understandable.”

Warmth in the void

When Kemal Gunel was seven or eight years old, his father woke him up in the middle of the night to watch 1979’s Alien.

“That was trauma for me,” he says now.

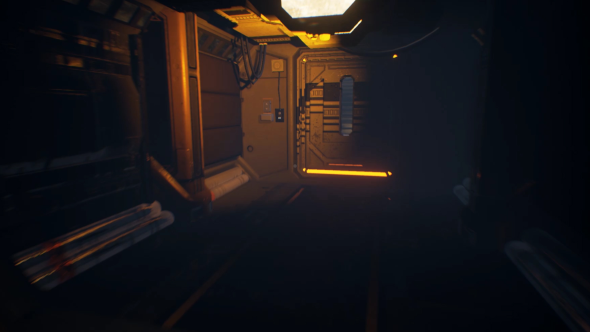

But ever since, Gunel has been driven to recreate the film’s terrible beauty, first as a lighting artist on film sets, and now as a 3D artist on Tartarus. There’s a distinctive warm glow to the screenshots and pre-release footage that already taps into the retrofuturism of Ridley Scott.

“I learned a lot of tricks from his movies,” Gunel elaborates. “Generally I put a main light in the area to see the general geometry, and slowly start cutting it with shadows.”

Tartarus’ retro stylings suggest the incandescent lamps of the era before energy saving, which Gunel brings about through a combination of warm orange and light blue colours. It sounds easy, but this sort of simplicity is difficult to achieve – a painstaking process of lighting desks, computers and ceilings piece by piece, while remembering to step back from time to time and take in the scene as a whole.

“Leaving the computer for ten minutes is really important,” says Gunel. “Because you end up being blind to differences. Try to imagine you are there, you saw that place, you know that smell. You know that rusty texture on the metal wall.

“You have to understand this: geometry, light, and texture are the brothers of hell,” he adds. “If one of them fails, all hell breaks loose.”

Tartarus comes to Steam this summer. Unreal Engine 4 is now free.

In this sponsored series, we’re looking at how game developers are taking advantage of Unreal Engine 4 to create a new generation of PC games. With thanks to Epic Games and Abyss Gameworks.