Perhaps there’ll be a time when we reminisce fondly about streaming errors, or Netflix’s lacklustre movie catalogue. It’s tough to imagine now, but nostalgia has a way of rendering past annoyances quaint, and of lending new charm to once-perfunctory sights and sounds.

Related: the best PC indie games.

In TV Trouble, a game that has you working as a TV repair person in 1967, it’s the plastic clunk of analogue buttons and the gentle wash of white noise.

“I was born in the early 90s, so I’m old enough to have experienced the analogue era for the early part of my childhood, but not old enough to have been steeped in it for years and years,” says co-developer Ben Wilson. “I think there was something memorable about the satisfying tactile feel and sound of buttons and dials that’s absent from modern home technology.”

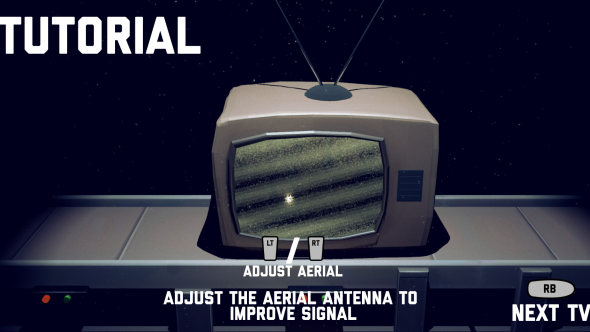

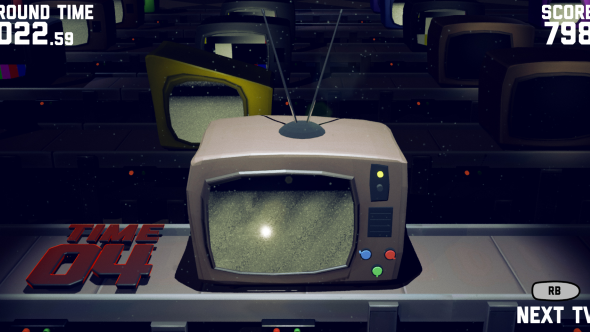

As faulty machines lurch down the conveyer belt before you, you’ll prod away at each in an attempt to produce an image on the screen. Some have antennae to bend and multiple knobs to twist. Others have a seemingly arbitrary number of channel buttons to flick through. If you’ve done something right, you’ll be rewarded with the sudden blare of the strings in a Western score, or a clear view of an advertisement for tyres. Then it’s onto the next one.

“There’s something about the way video artifacting looked and sounded in the analogue era that had a weird sense of character to it that is no longer a thing that exists,” notes Wilson.

Wilson made TV Trouble with Kathy Zalecka, Dan Cohen and Al Taylor, friends from university who have since developed a “working rhythm” through 48 hour game jams. This particular project came together over a weekend on chat client Slack last February.

After an evening spent throwing about “goofy ideas”, Wilson’s partner chimed in with the suggestion of a game about TV repair. Wilson was drawn to it, taking his cues from WarioWare.

“I always liked how that game just sort of kept going, without ever pausing to give the player a moment’s break,” he explains. “The comedy and the flow of that game comes from the endless bombardment of tasks you’re given as a player.”

TV Trouble, it was decided, would be a time attack game – a hectic conveyer at odds with the wistful period imagery. Wilson pictured the player as a nameless worker in a huge, uncaring company, overworked and disgruntled. You’re given an intricate task that requires concentration – turning the dials is somewhat reminiscent of the tumbler minigames in Thief or Fallout – but not nearly enough time to perform it comfortably.

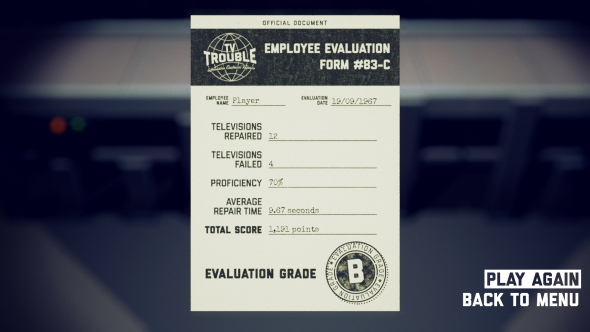

For a little while the team contemplated giving the player limited lives for failing individual repairs – but caring so much about each TV didn’t match the premise of a worker paid too little to worry about the machines that slip through the net.

“Letting players freely give up on a TV they were stuck on without having it lose them the game felt more appropriate,” says Wilson. “I like that the game is sort of indifferent about whether or not the player is doing well.

“Your individual actions aren’t as important as the overall momentum of the production line you’re on. When you run out of time on a TV, the game doesn’t stop to punish you, it just moves the conveyor along. I think this works well to make players feel like a tiny cog in a machine.”

The team worked in Unreal Engine 4. Its visual scripting system for non-programmers, Blueprint, is “pretty much the single reason” Wilson has been able to spend the last few years making games like TV Trouble and Button Frenzy. For TV Trouble, he built a system that dynamically shifts the pitch of a machine’s audio as you’re tuning it in.

“A straight fade from static to clean audio felt too artificial,” Wilson expands. “It’s one of those little bits of polish that is probably hard to pick out on its own but helps to cement the experience.”

The images themselves came from a free archive site, where Wilson had previously dug through footage of ‘60s television. He had become interested in the sometimes blunt adverts, a world away from today’s, and the way the “appallingly offensive” was presented as the norm.

“There’s so much material up there that you can kind of steep yourself in it and just imagine what it might have been like to live in that time period,” he says.

Zalecka whipped up 3D models and art to match, and TV Trouble became perhaps the first ever period piece time attack game.

“I liked the idea of presenting the player with little snippets of history as they played,” muses Wilson. “I think mostly it just helps to give the game a concrete sense of time and place. I’ve had a few people tell me that the game feels eerily nostalgic to them which is pretty cool.”

The four friends showed TV Trouble at last year’s EGX in the Leftfield Collection, and it’s now been released for free on Steam.

“Most of the stuff we’ve worked on as a team is available online so it’s super easy to go back and see the difference between the stuff we first made and the stuff we’ve made more recently,” says Wilson. “It’s like the wall you’ll often find in a family home that has markings to record the kids’ heights over the years.”

TV Trouble is available for download on Steam. Unreal Engine 4 is now free.

In this sponsored series, we’re looking at how game developers are taking advantage of Unreal Engine 4 to create a new generation of PC games. With thanks to Epic Games and SUPERCORE Games.