Cast your mind back, like a grappling hook into the dark, to when Bossa Studios first announced Worlds Adrift. It was a surprise. The London studio had made a name for itself with Surgeon Simulator and I Am Bread – games that were not afraid to make physical comedy their focus in a market dominated by self-serious worldbuilding.

Read more: what’s the potential for games using SpatialOS?

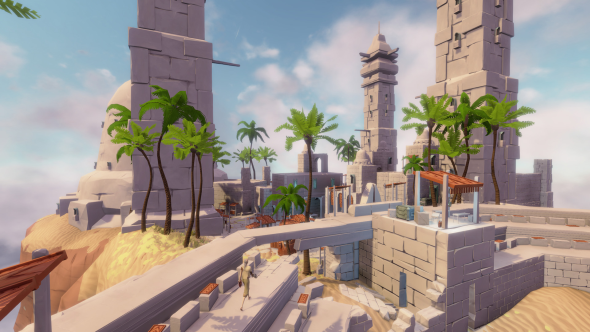

Worlds Adrift, at first glance, looked nothing like that. A vast sandbox of floating islands where your crashed vessel might leave permanent wreckage in the world, it had an eerie appeal of its own. But where was the Bossa in it?

Those who have played Worlds Adrift on Steam since the summer of last year now know the answer to that question. From their first climb through a ruined tower onward, they have wrestled with physics just as they did in I Am Bread – flinging themselves from buttress to outcrop rather than toaster to counter. And the physics goes further, influencing the designs of player airships, which are governed not just by creative ambition but weight, aerodynamics, and fuel consumption.

“We like to play with the controls and give you something immediately, tangibly different when getting your hands on the game and moving around that space,” game designer Luke Williams tells us. “You instantly start having fun. That’s usually what we try and go for.”

There is another, less obvious throughline for Bossa – from their early designs for ambitious online play. “The company was founded to try and revolutionise the multiplayer side of things anyway,” Williams points out.

That revolution began with Monstermind, a rare attempt at real-time PvP in the invite-based world of Facebook gaming that wound up winning a BAFTA. The follow-up, an RPG based on the UK TV series Merlin, was upstaged by the surprise success of Surgeon Simulator. “Four of us made it over the weekend and then it blew up virally on Monday,” Williams remembers.

Bossa’s DNA is embedded throughout Worlds Adrift, then: an attempt to fold the fun they had making physics-based games back into their original mission. At first it sailed perilously close to failure – deemed too ambitious and shelved for three or four months back in 2014. But then the studio met the perfect partners in Improbable, the makers of a cloud-based technology called SpatialOS. The tech combines servers to allow for MMOs with persistent worlds and, most crucially, real-time physics on an unprecedented scale.

Now, on Steam, it is the intersection of Bossa’s two histories that makes Worlds Adrift different from other MMOs.

“A big draw of Surgeon Simulator and I Am Bread is that they were inherently difficult to play,” Williams says. “There was no progression in the game of levelling up your hand so you could grip things for longer. It was pure, mechanical player skill.”

Sure enough, Worlds Adrift characters do not accrue power through increased stats or level-specific items. The grappling hook you wield clumsily at the beginning of the game is the same a veteran uses to swing like Spider-Man. The only difference is practice and hours spent studying YouTube videos. This levelled – or de-levelled – playing field has a flipside, too: even the most experienced players are vulnerable to a well-placed shot from a pilot who joined the game yesterday.

“You’ve got the same HP,” Williams notes. “What it boils down to is who can aim better. You don’t become a demigod.”

What do Worlds Adrift players covet if not maxed-out XP caps? They chase the ancient technology left behind by extinct factions. Tens of thousands of words have been written on the cultures and traditions of the nations that existed before the world broke apart, and this foundation governs the aesthetic and lore of the items Bossa create. But you will have to work for it.

“Our lead artist is a big fan of Dark Souls, and he liked the fact that they didn’t have a book that was the history of the world,” Williams explains. “What they did was they seeded it throughout in items and inscriptions, so you could slowly over time build up what the world was. That’s what we have in Worlds Adrift.”

Long-term players come to wonder about the propulsion mechanisms that power their flying boats, and the civilisations that came before take on the allure of real-world ancient history – a story to be extrapolated through archaeology.

“We make sure that, if you start in the region of one culture, the stuff you find is biased in some ways, like finding a newspaper clipping from Nazi Germany,” Williams says. “So when two players meet they have a completely different opinion of the world, and realise they’ve been reading propaganda the whole time. Almost subconsciously, you’re feeding on it without realising.”

The finest examples of worldbuilding in PC gaming are layered with history: think of the way Combine tech suffocates the Eastern European architecture of City 17, or decay undermines the utopian optimism of Rapture. What is unique about Worlds Adrift is that the next stratum is being laid right now. As players build their skyships and tear others down, SpatialOS allows the detritus of their adventures to persist indefinitely, becoming part of the fabric of the world.

“We’re not going to add more lore,” Williams says. “From now on, it’s the stories that players build. They’re piecing together a new society, and our ultimate goal is that they will build these grand skyports and instill either anarchy or peace and trade in a region. That will become the new story.”

This article is part of a series of features sponsored by Improbable. Visit their site for more on games using SpatialOS.