Eve Valkyrie might be free from the constraints of gravity, but there’s plenty of weight on its shoulders. CCP’s team aren’t fulfilling just the one dream, of VR dogfighting – they’re also charged with redrawing the Eve universe in unforgiving close-up for the first time.

That’s a lot of pressure for a low-pressure shooter to handle. But on the phone, the wonder its developers feel for the game they’ve made together is audible. They’re buoyed by a vacuum that’s become “infinitesimally more and more beautiful” as they’ve rebuilt it in Epic’s new engine.

The Valkyrie team are still sustained by the enthusiastic push Eve players gave them back at the studio’s Icelandic Fanfest in 2012. The show demo was built by a five person team working in their spare time – but reception was such that Valkyrie suddenly became a fully-fledged CCP project.

A team was assembled in Newcastle after work wrapped on Dust 514, and the decision made to port the Unity prototype to another engine. Somehow, that new version of Eve Valkyrie in Unreal Engine 4 was playable by the time we saw it in the middle of last year.

“It was a pretty quick transition process,” said technical director Richard Smith. “A lot of that was to do with the experience we had on the team, because we knew how to make the right technical choices first time around. Epic have put a lot of work into the tools – and for all of that code we wrote back at the beginning of this year, there’s very little we’ve had to go and revisit because we were very familiar with a lot of Unreal’s systems.”

The prototype team had already worked out the fundamental principles of their dogfighter, and the role VR would play in it. The rebuild, then, has been about “making good better” – finding out what was new in EU4 that could improve on what they already had.

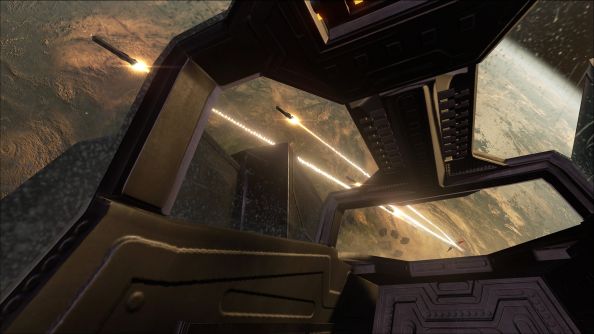

Cockpits are a strong case in point. In the demo version, CCP created a framework for their depth and scale that felt right in VR. But they “never really pushed visually”.

“We’ve really started to think about these cockpits and get deeper into them – what they are and what they do, how they’re represented,” said 3D artist Andrew Robinson.

“In UE4 we knew we could throw around a bigger poly count, and the lighting was more accurate with physically-based rendering. And the knowledge we had of Unreal shaders meant that we could fill the cockpits a bit better, make them more of the characters that we wanted them to be.”

CCP have thought a lot about the character and personality of the world they’re building in Valkyrie. They’re working with a pre-existing universe: 10 years of story, 10 years of evolving races, and 10 years of established aesthetic.

“We have all this narrative and the racial definitions are so strong that we can take those and build new things from that,” said Robinson. “It’s the perfect backbone for building a world of great fidelity for VR.”

For the existing Eve community, the fantasy of Valkyrie is seeing the world they know recreated at a granular level. It offers, literally and figuratively, a new perspective on the ships and battles players have watched from on high for so long.

“We’re putting you right inside them with the bolts and wires and really giving you a sense of scale – a sense of ‘I’m the smallest piece of this huge battle’,” enthused Robinson. “In Eve it’s a small speck, but we’re taking you right down to that level. The base ships are even bigger now. We’re down inside that world, like tiny ants in a huge wrestling match, just scurrying around.”

Doing justice to that fantasy has been an awful lot of work. The low-poly ships of Eve Online were never designed to be inspected in first-person. In order to “push the detail”, the Valkyrie team needed to return to eight-year-old, original concept art and rebuild the vessels from scratch.

It’s clear it’s been a privilege for the Newcastle team, to finally construct those first ships in all the detail they were first imagined. But it’s also been a technical challenge.

For starters, low-res objects that would pass unnoticed on a screen will cause wobble and jitter in VR. What’s more, the incredible size of the planets, stations and other landmarks in Valkyrie’s vacuum can lead to some serious cases of Dougal syndrome – the inability to tell a small-but-near object from a large-but-distant one.

You might think the problem would be easy to solve in three-dimensional VR – but it turns out poor stereo perception renders small and large objects “indistinguishable” once they move beyond 10 metres from the viewer.

“Even in VR, it’s very difficult to tell something that’s 100 meters away from something that’s a kilometer away, except by the level of detail and having that human-level scale on those objects,” explained Smith. “We’ve had to put a lot of detail into the assets out there in the world because otherwise you couldn’t really get a sense of how far away you were from them.”

Solving the problem has required a change in mindset from the art team, and a willingness to exploit the tools that come “out of the box” with Unreal Engine 4.

“UE4 helps you extend those systems and also make it work in multiplayer,” said Smith, “so you can have ships that have millimetre details in them, yet could be tens of hundreds of kilometers apart, moving at hundreds of kilometers an hour.”

The engine’s capacity for quick iteration has proven essential for working in VR, too. UE4’s blueprint system allows designers to link up systems they’d ordinarily have to bother programmers about, and CCP have used it “quite extensively” to test features in-engine – before passing the results to the team’s experts.

“It’s just the immediacy of being able to hook things up and put things together very quickly,” said Smith. “Particularly when traditionally we would have relied on an iteration cycle that went back and forth between content creator and programmer.

“The content guys are now able to work directly in there, bash things together to get them how they want. Once they’ve essentially figured out what a feature needs to be and how it needs to work, they can hand it over to the programmers to create their optimal code systems and make that stuff work.”

“There’s no firm rulebook for VR yet,” pointed out Robinson. “We’re writing quite a lot of it right here in the studio. As we’ve been working, rapid prototyping has been absolutely key to getting the right pieces together and finding what works in VR. Does it feel good? Does it feel bad? Can we make it right or is it straight up not gonna work?”

Maintaining that stable test environment has been tricky. A VR game running at less than a solid 75 hertz quickly becomes uncomfortable – not just for testers, but for the developers playing it every day. That’s left CCP fighting to keep the game in an optimised state throughout development – an unheard of standard for pre-beta games.

“We’re used to pushing beautiful content into the game in development, and then getting to the optimisation stage and making it run a solid 30 or 50 hertz on whatever console or PC we’re targeting,” said Smith. “We’ve had to put a lot of emphasis on performance, on optimisation, even in our early prototyping phase.”

There’s still a lot we don’t know about Valkyrie as a game – Smith and Robinson talk about “building exciting paths” through an environment with no clear axis or direction, and reference a day/night cycle that must surely be unlike anything we’ve seen in a planet-bound game world. We don’t know how it’s going to work as a full-length experience.

But the team are already proud of what they’ve built. As Smith puts it, any VR developer can be proud if they can run a “beautiful looking world” at 75 hertz on the Rift’s dev kit 2. There’s a sense that CCP are colonising previously inhospitable systems – pioneering VR techniques for a AAA industry that’ll be working with Unreal 4 for years to come.

“We’re the first VR game in UE4, possibly first on the planet, to do cross platform play between both Oculus and Morpheus, and getting as few changes between the two as possible,” said Smith. “I’d like to think that a lot of the improvements that Epic are pushing out in their VR implementation, they are from the feedback that we’ve been giving.”

Eve Valkyrie will be an Oculus Rift launch title. Unreal Engine 4 development is available to anyone for $19 monthly subscription fee.

In this sponsored series, we’re looking at how game developers are taking advantage of Unreal Engine 4 to create a new generation of PC games. With thanks to Epic Games and CCP.