The past two years has seen the biomedical research charity the Wellcome Trust ramp up its activity in the gaming scene. Their exhibitions on DNA, Drugs, and Dirt were each coupled with a game to explain some of the core concepts –Axon, High Tea, Filth Fair – and they provide large funding packages for those using games to explore scientific concepts.<br><br>We caught up with the Trust’s gaming consultant Tomas Rawlings to talk about the 2012 ExPlay Game Jam and their Gamify your PhD initiative.

PCGN: Why has the Wellcome Trust taken an interest in games?

Tom: The guy who founded Wellcome, Henry Wellcome, was passionate that science was a part of human culture and that you didn’t see a separation between the two. So part of Wellcome’s mission, in addition to these big major challenges, is to engage with people so that they see science and culture together.

Games are a great method to talk about science because games by their nature are dynamic, they’re interactive, and science is very hands on. So if you want to explain to somebody a complex system whereby as you change what’s in the system the system changes as a result, games are a great way to do that because rather than just talking about it you can let the person experience it themselves.

I mean, ultimately, if you think about what a player does when they play a game they are using the scientific method, I mean they get dropped into a game on the first level, you don’t know the rules of this new world, so what you have to do is trial and error to figure it out, and by trial and error you construct a set of rules in your head “If I touch this object I die, whereas if I jump over it I’m OK” and ultimately they are constructing a series of rules to help them navigate that world. And really, that’s what science does. It’s by trial and error, by experimentation we construct a series of rules that allow us to understand and engage with the natural world.

I’m keen to see that sort of thing happen and hopefully out of the game jam that will exemplify what I’m talking about in using the science and the gaming to engage the user.

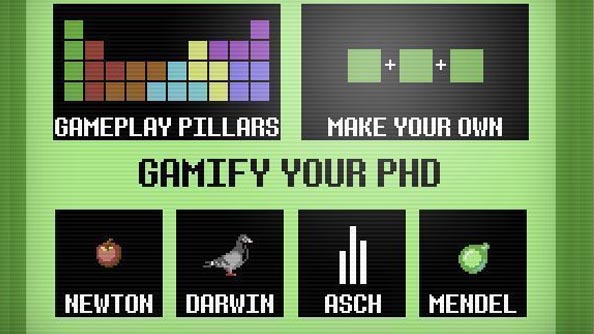

Tell me about the game jams. You have the two, Gamify your PhD that’s happening next week and the Explay Game Jam that’s coming up in October, right?

Gamify Your PhD is actually slightly different from a game jam, there’s a methodological similarity, but with Gamify Your PhD we’re putting the scientist in the role of the game designer. So the scientist is building the game with the backup of developers to help them; that’s why we have fully formed teams of developers working with them: they’re used to working with clients, they’re used to supporting them, so it’s a slightly different approach. Whereas the ExPlay game jam is open to the public, it’s free – people can just sign up and take part – there’s a bit more, game jams by their nature, they’re a bit more you don’t know what you’re going to get out of it. There’s a lot more surprise in it, so that’s great.

They’re two things that share the same root method but they’re trying to arrive at the same sort of thing which is great games with great science, but by very different routes and in a way I don’t really know how they’ll perform in relation to each other. They’ll both produce good results, but they’ll both produce very different results.

So is the ExPlay Game Jam following a pretty traditional formula?

It will begin with the scientists involved presenting the theme. Obviously, because Wellcome are involved it, will be something to do with Biomedical Science. But, again, it will be looking for something creative from that, the scientists will be there to present the science and they will be on hand for any of the teams to talk about it. What we’ve found from running collaborative workshops between scientists and creatives, developers, and people like that is that the initial presentation of the science is a good starting point but actually what works very well is when you can have a chat with the scientists and drill down into the subject, you find some very fascinating game hooks in there. So we’re keen for the scientists to be around, to be on tap basically, to be used as a resource. So they won’t be joining any of the teams but they will be available to all of the teams to be used as a resource.

The scientists will also take part in the judging panel at the end because there will be some awards. Like most game jams, the taking part is really the biggest thing, the enjoyable thing, but you also want to celebrate the achievements that come along. So there’ll be a few prizes and there’ll be awards which will be awarded later. The actual awards ceremony will be rolled into the ExPlay Festival’s awards ceremony, the TIGA awards.

What’s Wellcome looking to get out of this?

A couple of exemplar games that really do well. In fact, we will be encouraging all the participants to look at Wellcome’s funding strands at the end of this. So if a game’s gone particularly well, it’s got a lot of potential to engage people in Biomedical Science, let’s get a funding application going.

What sort of funding’s on offer to developers?

Game studios can apply to Wellcome to get a pot of money that varies in size from £10,000 upwards, there are much larger awards that Wellcome sometimes makes for projects that meet with those aims. Part of my role is to encourage more games studios to look at these pots of funding and apply for them. And though I’m keen they contact Wellcome first rather than just apply; it definitely helps to have a grants advisor to chat to them. It’s in everybody’s interest that the people who apply have the right information they need and it’s the right funding for them. The more funds that get approved the better.

Plus, in talking over an idea, you could redirect a project, refine it into something better.

Tom: Yes. There’s also very important distinctions on what Wellcome does. Wellcome is interested in biomedical science not, for example, public health. While there’s a degree of overlap between those it’s crucial that it hits those biomedical science areas for Wellcome to be interested. But it’s also – and this is one of the really good things about working with them – they’re not didactic about it, they don’t want to ram science down people’s throats.

What they want is, and it’s back to that point about science and culture being together, they want to see content where the science sits naturally. Like, one example, Deus Ex: Human Revolution, it’s not a Wellcome project but it’s a great example of where cutting edge science has informed the content of a mainstream game, and I think it’s a better game as a result or having that scientific credibility and yet at the same time the game play isn’t compromised at all, it’s a brilliant game.

It’s not always about the money, although the funding is an important bit of what Wellcome does, it’s also about the scientific expertise that are on offer, the ability of Wellcome to work with people to bring ways of operating that just wouldn’t happen without their help.

They have this massive untapped resource of scientific minds to be used to inspire, if you’re doing a game and it has some sort of DNA aspect and you though “Well I’d like to know a bit more about this”, we can put you in touch with a scientist. Wellcome also looks at games in regards to education, especially what they call ‘Informal learning’. So Wellcome’s interest in games is pretty wide reaching, which is why it’s important to be strategic about it because there are lots of areas it can touch on.

Thanks for your time!

The ExPlay Game Jam is taking place in Bristol and London this October and is currently open for registration. It’s free to take part but there are a limited places, so go here to secure yours.