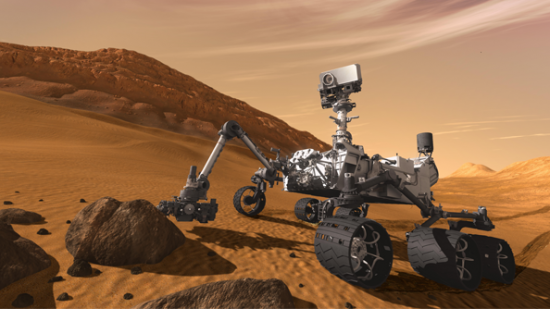

Did you know that the cutely named Curiosity rover is the size of large family car? Just look at it. It’s got lasers for eyes. We sent it up to Mars to find life, but if there is life up there it was either crushed on impact, or is cowering behind rocks.

We’ve been firing robots at Mars for decades now, each a little bit more advanced than the last. The first Viking probes began by sending back a few digital photographs, but by the end of the program they were digging trenches, analysing soil samples and tasting Martian air. It’s that progress that Take On Mars tries to replicate.

I kind of love it.

It’s a weirdly simple game. There is a map of Mars and on it are mission sites. You have a small budget to begin your program, and start exploring and completing missions like photographing the rim of a crater, or taking soil samples.

Most of the missions are remarkably hands-off. The Viking style landers you’ll first use, for instance, weren’t mobile, so you’re more likely to be moving the camera around, rather than jauntily rolling over Mars.

As your budget increases, so does your technical prowess: a small development lab allows you to add and bolt on new instruments to your rover chassis, before launching them.

It’s a thin game. More of a framework. If you’re not that interested in Mars exploration, then you really shouldn’t be playing it. But I think it’s gorgeous. I nearly burst into tears playing it.

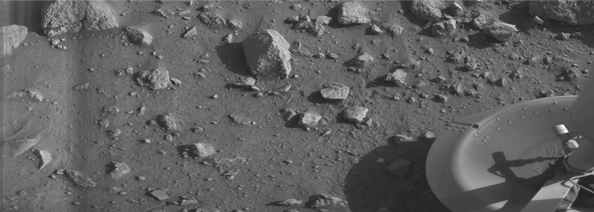

Here’s the first photograph the Viking Lander ever took.

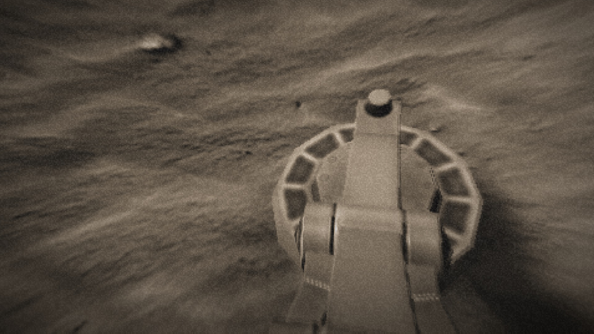

Here’s the first photograph I took with my first lander.

AMAZING.

This isn’t Kerbal, with it’s overarching, free-form orbital genius. Instead, Take on Mars is the equivalent of those industrial machine simulators, a digger sim, but in space.

Everyone has an obsession. Mine is spaceflight. Space, the exploration of, and the eventual colonisation of, is a dream, but a dream that we’re within touching distance of. I’ll almost certainly never get to Mars, never see the inside of the Victoria crater, but maybe my grandchildren, or their children, will.

For a few fleeting moments, through the grainy eyes of my Viking’s 70’s era digital camera, I had that privilege. That’s amazing.