Whether to venerate or deplore the struggles of the over 70 million military personnel who were mobilised during World War One is an impossible conundrum. The facts are unchanging: nine million soldiers and seven million civilians died, 20 million people wounded, thousands of soldiers drafted in from all over the Great British, German, Russian, Austro-Hungarian and French colonial empires, more than one million wounded and killed in the Battle of the Somme alone. On paper, we have no right to get squeamish about the First World War when we have no problem playing a game like the original Call of Duty, which is set in a war that claimed the lives of 60 million. So why does Battlefield 1 make me cringe uncomfortably whenever I hear about it?

Prefer observing from above? Try the best PC strategy games.

It first set in with the blockbuster reveal trailer. Biplanes zipping around like X-wings, a dubstep remix of Seven Nation Army, men battering each other with shovels and someone being engulfed by a cloud of mustard gas. It’s a nightmarish cavalcade of tactlessness – one that’s so far removed from the reality of that conflict that for DICE to claim any semblance of authenticity to it should be out of the question.

Looking at it purely from an industry perspective, DICE deserve credit for bucking the modern/futuristic trend set in motion by Call of Duty 4. It’s a decision that’s rewarded them with 44 million views and one million likes – making Battlefield 1’s reveal video the most watched game trailer on YouTube as well as the most liked ever on the platform. It works because it’s pure spectacle, and is offering its audience something they haven’t played before, at least in this particular flavour.

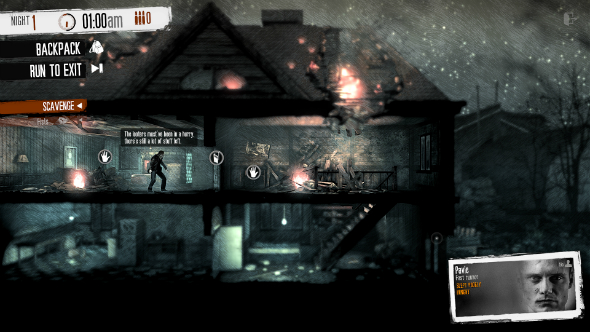

By contrast, games like Verdun, This War of Mine and Valiant Hearts work because they tell their stories on a smaller scale, distilling the elements of one experience into something that’s sharp and unforgettable. Verdun takes the trench warfare that most of us associate most strongly with the Great War, and condenses it into a multiplayer shooter wrought with tension. Much like the Battle of Verdun itself, the game’s matches are asymmetrical. Attacking is an uphill struggle against machine guns and snipers; it feels futile but you know it’s not. That’s because from the defender’s perspective the battle feels totally different. It feels like you’re up against a ceaseless tide of enemies swarming across the expansive and uneven terrain. Making a central game mechanic out of trench combat rather than trying to find a way around it is Verdun’s greatest strength.

Then there’s Valiant Hearts, which effectively takes the player on a colourful tour of the Western Front, but manages to do so while still being one of the most thoughtful, affecting and uplifting war games ever made. Without a combat mechanic to speak of, Valiant Hearts gives two perspectives of the war and in each one chooses to focus on the human tragedy of it rather than the battlefield experience.

It’s a similar approach to the one adopted by This War of Mine developers 11 bit Studios. Senior writer Pawel Miechowski tells me about how his team approached the Balkans War, and how war should be depicted generally. “I think on the high-level design, one of the pillars was to approach the topic with the proper respect. Without it, we could be considered creators who are cashing in on war. So the proper respect for the topic required research, talking to people who have survived war. But it was also staying away from any political connotations because that raises unnecessary emotions, especially in the Balkans. It really was a civil war: brothers were fighting brothers. It was also not so long ago, so people remember it very well. Putting a conflict in a specific political time and place would add unnecessary and unwanted context.

“I think the entirety of pop culture trivialises war. On the one hand it’s a very thrilling topic, on the other hand, we see it from a distance and forget how horrible an event war is. In the end it somehow happened that as a prolongation of that, pop culture trivialised war. It’s happened to a bigger extent in gaming, because at some point war and fighting became a dominant topic. For that, This War of Mine can be considered an antidote, because we presented war in the serious tonality that it deserves.”

I’ve always wanted a game to be set in the First World War. With military operations being conducted in Australasia, the Balkans, Egypt, Russia, Western Europe, Africa and Asia, the First World War was a truly global conflict. It’s also one that took place in an age of industrialisation and modernisation, where many of the technologies that support modern society were in their infancy. Battlefield 1 appears to be heavily drawing on both of those themes, but in doing so DICE are bastardising the reality of the war.

The zeppelins that you see marauding the skies above Battlefield 1’s multiplayer maps simply never were. Airships in the First World War were terroristic – they were behind Britain’s first Blitz – carrying modest payloads far beyond enemy lines in order to strike at infrastructure and morale. Even in use over battlefields, zeppelins would often operate from high altitudes so as to avoid being targeted by planes, limiting their combat effectiveness to strategic bombing, not machine gun strafes. Likewise, handheld machine guns that could be fired at the hip are mythological – most heavy MGs weighed more than a border collie, making the the notion of hip-mounted fire risible.

Taking some historical liberties is fine, and nobody would expect or want a First World War Battlefield game to rigidly adhere to fact.

Then DICE announced Elite classes – think jacked-up, armour-clad knights of yore, wielding 40-pound machine guns while striding around the battlefield like Darth Vader on ‘roids – and any notion that this was to be a remotely respectful take on the conflict vanishes amidst the premise of players being able to turn the tide of battle by spawning in as a special trooper. As DICE tactlessly put it in their Elite classes announcement post- “Not every soldier is created equally.”

DICE are moulding the tech, tone and reality of World War One so that it fits their steampunk, rodeo show of a multiplayer shooter. It was a formula that worked for Battlefield: Bad Company 2, a game that claimed no ownership to a particular war or scenario, but instead focused its effort on a cast of characters and a set of tools. DICE’s representation of the Great War would be unique and interesting were they not insisting – in spite of evidence – that it’s going to be a faithful, World War One shooter.

By drawing on the mechanised aspects of that conflict DICE could have created an alt-history steampunk FPS that was as mad as the one that Battlefield 1 is shaping up to be – a historically branded First World War game with American troops but no French ones (until the DLC arrives), Battlefront-esque Elite units and vehicles that appear to handle like they’re modern racers. Almost every element of it is pure fantasy, but still DICE cling to their claim that they’re making a World War One game.

None of this is to say that representations of the war should be limited to the Western experience of World War One: endless, stagnant bloodshed, tinted only with misery and futility. The works of Wilfred Owen and Siegfried Sassoon have come to colour our perception of the Great War, but it only reflects one section of it: trench warfare. DICE have tried to bring every facet of a sprawling conflict into one experience. That means giving players agency in a setting where, historically, that concept would be farcical. On the flipside, bringing the technological advancements that were seen in the Western theatre over to Africa and the Middle East is equally problematic – every battle is different, and they don’t all fall under one set of tools and tactics.

It’s important not to ignore the elephant in the room: gaming is a form of entertainment. So however uncomfortable Battlefield 1’s approach to World War One might make us, it is just a game, and from what we’ve seen of it, a good game. The problem is that cherry-picking the best bits of a global tragedy just leaves a sour taste in the mouth. And that’s how we remember the First World War, as a global tragedy.

Compare it to the dominant themes that make up our collective perceptions of the Second World War, a straightforward fight between good and evil in which Nazi Germany stars as the mustache-fiddling villain, and a very different picture emerges. It’s easier to take liberties with the Second World War because it had archvillains who committed genocides and developed superweapons in laboratories. From Call of Duty to Wolfenstein, developers haven’t struggled with creating a tasteful war story because they’ve always had a unanimously despised enemy.

Even hugely successful mainstream franchises like Call of Duty and Medal of Honour managed to find a respectful tone in their games within the most life-consuming conflict in history. Call of Duty shed light on the experience of a Russian infantryman. You were shot for dissent, given ammo and ordered to pick up a fallen comrade’s rifle; every moment of that game felt like a Herculean struggle against all odds to stay alive. Every soldier had a name, allowing the player to watch an endless tide of privates run past them into a gauntlet of explosions and machine gun fire. These games gave players a sense of perspective over what they were doing: you might be the one activating the explosives and storming the trenches, but the heroes lay scattered across the battlefield or still charging forward around you.

There’s also the concept of agency that makes World War One a difficult subject to approach, especially from a gameplay perspective. The image of troops advancing over no man’s land has always been recognised as a sort of mechanised slaughter, in which both sides take it in turns to have a go at their opposition’s trenches. It’s a long way from the urban fighting and squad-based tactics that we associate with the Second World War – men were still mowed down in their thousands, but we don’t picture it that way.

Unlike in World War Two, the events of the Great World War weren’t being serialised on film and TV as they were happening. Men returning home could expect their loved ones to know little of what they had experienced on the frontlines – their stories only emerged over time, and with time they gained reverence. In Britain, newspapers and letters sent home were ruthlessly censored, removing any material that might undermine the nation’s morale. Rumours and negative reporting did creep out, but few civilians had any concept of how the war was being conducted. The result was that when stories were told, they were told by those who had first-hand experience of the fighting.

These bitter tales of sacrifice leaked out beneath a haze of pro-war fervour and patriotism. When the war ended the stories seeped further still into our collective conscience, but any pro-war sentiment had long since dissipated. The technology and artistic freedom to make movies, TV or games about the First World War came about long after the armistice was signed in 1918.

Films and newsreels were being made about the Second World War while it was happening. Casablanca, The Day Will Dawn, The Great Dictator, Desperate Journey and Edge of Darkness were all films that used the war as a central theme or plot device before the war was even over. Fast-forward to games like Call of Duty and Medal of Honour and it’s easy to see how the 60 years of scripting that preceded them have changed our perception of how the war actually played out. It also meant that by the time we got to play these games, there was nothing left to shock or offend us. Medal of Honour: Allied Assault even collaborated with Spielberg for its Omaha Beach landing sequence, and wasn’t afraid to lean too heavily on Saving Private Ryan in its other missions.

World War One has no particular filmic legacy to rely on. Likewise, it still strikes an emotional chord with many because it hasn’t had a buffer of media to desensitise audiences to its reality. There’s nothing inherently wrong with Battlefield 1’s choice of setting, although the inclusion of mustard gas grenades – chemical weapons being a war crime and all – is questionable to say the least. The problem comes with certain elements of that setting: the muddling together of tech and tactics from different theatres of war, the glossing over of key belligerents like France and Russia and the general game-ification of it all feels, for all of the above reasons, wrong.

DICE’s justification for some of this has been that trench warfare was just one part of a bigger war, in which a number of tactics and strategies were used. They’re right, but why force it all together into the same sandbox-esque multiplayer experience like it’s an episode of Deadliest Warrior? Taking the Battle of Coronel, Harlem Hellfighters and armoured trains and labelling the resulting fragfest as a World War One experience does a disservice to the memory of the conflict. It was a war rife with variation and experimentation, but those factions of soldiers and theatres of war deserve their own stories, not to be boiled down into playable factions and maps.