Cyberpunk is a relatively new genre. Most will refer to William Gibson’s 1984 novel, Neuromancer, as being a seminal work within cyberpunk, but its roots go back further to sci-fi authors of the ’60s and ’70s like Phillip K Dick, JG Ballard, and Alice B Sheldon (who wrote as James Tiptree Jr). Movie and videogame adaptations followed suit, cementing some of the key visual cues that we all recognise as cyberpunk today.

Cyberpunk 2077 is probably the most famous example in videogames – Gibson himself ended up commenting on the trailer, saying it “strikes me as GTA skinned-over with a generic ’80s retro-future.”

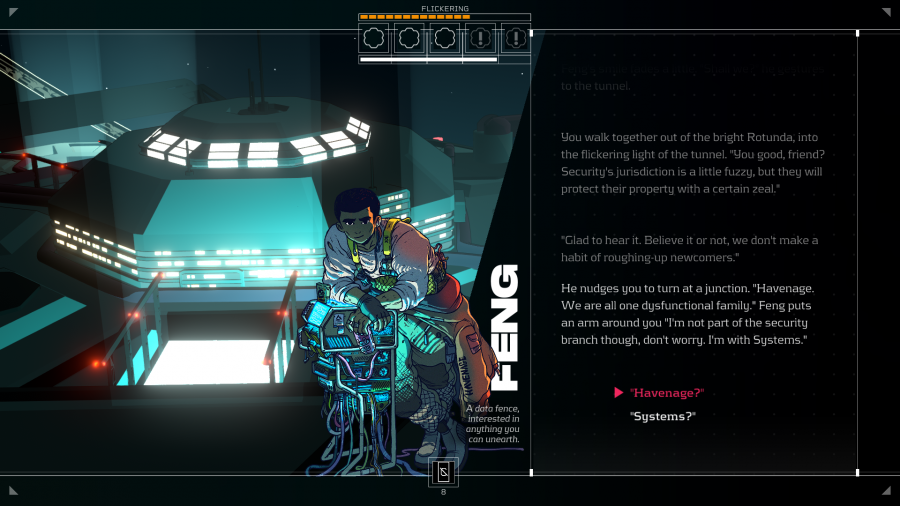

There are, of course, countless other cyberpunk games going all the way back to Konami’s Snatcher in 1988, and more still that are being made right now, like Citizen Sleeper. It’s a narrative RPG set on a lawless interstellar space station at the edge of society, where you play as an escaped corporate-owned consciousness. We spoke to Gareth Damian Martin, the solo developer behind Citizen Sleeper, about what cyberpunk means in contemporary gaming.

“Even in its origins,” Martin says, “cyberpunk was built on so many existing parts of new wave sci-fi, literary noir, and beat generation style – it always feels wrong to chop it out of history and treat it like some unique strand of art and media.”

“At the same time, I think there’s a contradiction here, because cyberpunk, when used as a descriptor within games, feels painfully reductive. This is because, as with many aesthetically striking styles, cyberpunk visuals have been cannibalised and reused so many times as to become an incredibly basic list of elements. A neon-lit, rainy megacity, techno-orientalism, implants, corporate control. We are all so familiar with these elements that we can recognise them instantly, and within moments the ‘cyberpunk’ descriptor will be applied.

“In games in particular,” Martin explains, “because we are talking about a very aesthetic medium, cyberpunk manifests visually, and in particular draws extensively from Blade Runner – just look at the recently announced Vigilance 2099.

“I think it is very telling that Blade Runner is the major influence, because actually that film strips away most of the more philosophical and literary cyberpunk elements of Philip K. Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep. He replaced them with some hokey gumshoe detective elements and a carefully honed aesthetic that smashed together film-noir moodiness and a new strand of orientalism and fascination with cities like Shanghai and Tokyo. This incredibly successful aesthetic, which owes a huge amount to the designer Syd Mead, eclipsed any themes the film might have had and cemented its place as an eternal sci-fi touchstone.”

It’s important to note that Martin isn’t enamoured with the genre, nor do they necessarily want their game to be viewed as part of it. They do, however, appreciate the work of Gibson.

“When I was first working on Citizen Sleeper I was rereading William Gibson’s Sprawl trilogy,” Martin says. “I started feeling that I wanted to make something that drew on so many of the things I liked about these books, without making something explicitly cyberpunk. Could I make something inspired by Gibson that didn’t pay lip service to the genre he helped create? For me Gibson’s books are filled with strong qualities: the razor-sharp and intimate prose, the focus on those on the edge of society, the terrifying power of capital, decaying megastructures that house burgeoning subcultures. I think all of these make Gibson’s early work very relevant and exciting to read even now.”

But Martin also believes there are plenty of unexplored ideas in the genre at large, which they hope to delve into in Citizen Sleeper. “In Gibson’s Sprawl books, hackers are more like mediums, who can contact the intangible forces that influence the physical world. I always found this to be a more exciting vision of cyberspace, and so in Citizen Sleeper I have also tried to engage with these ideas a little more, placing the player as a medium between the physical and intangible – not as a hacker sat behind a computer, but a being that can, simply by closing their eyes, slip into a dream which sits behind the physical reality of their environment.”

“Because of this I think of Citizen Sleeper as being in communication with science fiction as a wider genre,” Martin says, listing Cowboy Bebop and Ghost in the Shell as other key influences. Despite admiring Gibson’s Sprawl trilogy, Martin has some reservations. “From the vantage point of 2021, I think Gibson’s remix of the hardboiled noir fiction in these books is successful, but it comes with a lot of conservative baggage that no longer feels relevant. For example, his interest in Japan as a rising power feels aligned with a burgeoning cocktail of fascination and xenophobia that was common in pop culture of the 1980s.”

So what does Martin make of gaming’s most famous cyberpunk game? “In reality, much of what is bad about Cyberpunk 2077 has little to do with the genre. CD Projekt Red’s corporate practices, its eagerness to foster toxicity within its communities, the hype machine – it’s all created this miasma around the genre which will take a long time to dispel.”

Martin also feels that “Cyberpunk 2077 is fairly unambitious. It carries forward most of its ideas from its source material, the TTRPG Cyberpunk 2020. That game was a power-fantasy pastiche of cyberpunk imagery and ideas, which hasn’t aged well, so 2077 is also a genre pastiche that feels incredibly dated and out of touch.”

One of Martin’s main hopes for Citizen Sleeper is to challenge the pessimistic worldview that pervades the genre. “One of the accusations I always see levelled at cyberpunk or similarly dystopian sci-fi is that it’s supposed to be a warning, not a fantasy. We’re meant to read these works thinking, ‘what a shitty place to live, I hope the world doesn’t end up like this.’ To me this is nonsense. To talk about Gibson again, it’s clear he was writing about a world that he was fascinated and enticed by.

“I have already seen my work being accused of being bleak, of seeing the future pessimistically. But actually I see my work as being about hope, about finding a place, a reason to go on, about the importance of forming communities and bonds.”

Citizen Sleeper is set to release on PC in 2022. You can check out the Steam page here.