There exists somewhere, in game design and game development, a borderline mythical sweet spot between substance and readability. You want games that are full, that are rich, that have plenty to say and plenty for you to do. Simultaneously, you want something legible – I remember turning on Assassin’s Creed Syndicate, the first in-game pop-up telling me I had 150 Codex entries I could read, and immediately feeling encumbered and lost to the point that I didn’t want to play.

As mainstream games have progressed, they have also homogenized, and become generally fuller, longer, and more turgid. In almost everything triple-A, you can likely expect a sizable tutorial and a pause menu encyclopedia of inputs and features. The elegance of these components – these solutions to videogame distention – varies, but you’d be forgiven for feeling dismayed now at the prospect of starting a new Big Game.

There are exceptions – Red Dead Redemption 2, Cyberpunk 2077 – but if you tell me a game lasts more than 20 hours, nowadays, I’m quick to assume there will be a lot of junk, noise, and perfunctory, for-the-sake-of-it ‘content.’ After almost a quarter of a century, this is where the original Deus Ex – one of the best PC games in history, and progenitor to a new type of RPG we now call the immersive sim – continues to eclipse all of its successors.

Human Revolution and Mankind Divided, the two Eidos-Montreal prequels, are not without merit, but they contradict or undermine a key principle that makes the original Deus Ex one of the all-time greats. Yes, there are dozens of characters, multiple locations, long levels. But everything is designed and delivered with respect to economy. In modern RPGs, or open-world or sandbox games, the guiding developmental fundament seems to be retention, sheer retention – keep them in the game and playing for as long as possible.

You can imagine why this is. We have a gaming culture where extended running time is equated to greater value for money. If a player is not playing your game, it is also impossible to upsell them on a microtransaction or a DLC. The more lore, the more volume, the more ‘stuff,’ the longer the player is – metaphorically – standing on the lot. Deus Ex benefits from a time before these models, and that’s what makes it such a wonderful game to play in 2024.

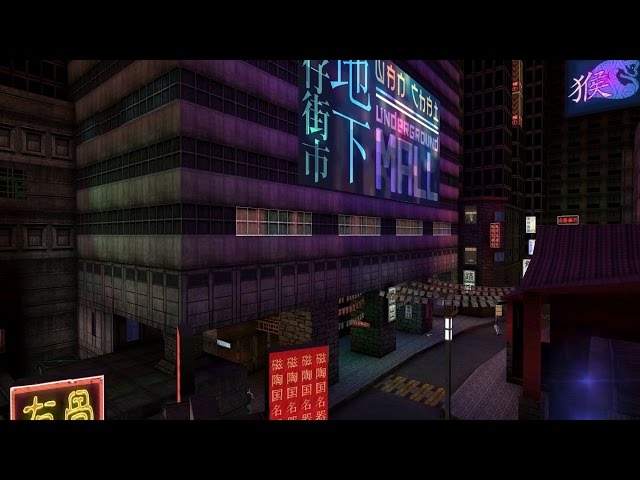

It’s substantial, both in the literary and aesthetic senses. It has a great look and a great sound; it also combats themes of identity, belief, nationalism, and loyalty. Deus Ex takes you around the world, from New York to Hong Kong and Paris, but has a static and well-defined set of core characters. You always know where you are, what you’re doing, and why. Likewise, every layer of the game’s mechanics is laid out for you in the first level, and all that changes is your ability to apply these tools with greater expertise.

Conversations happen in a few lines. Cities are consolidated into a couple of square blocks. The global conspiracy at the center of the narrative is neatly personified into four or five intimately drawn human characters. In an age where games feel bigger, and bigger, and bigger, not for the sake of benefitting narrative or enriching the drama, Deus Ex inhabits that nirvana between size and coherence.

To that extent, almost a full 24 years later, it feels incredibly modern, a combination of the subjectivity and authorial voice that we now synonymize with the ‘indie game,’ and the arresting production value of a triple-A.

If you miss the golden ’00s era of the immersive sim, check out some of the other best old games. Alternatively, scratch that Deus Ex itch with the best cyberpunk games on PC.