It took all of five minutes for Divinity: Original Sin to charm the pants – talking pants, no less – off me. Standing on a beach, talking to a flowery giant clam, I didn’t have a clue what was going on, and I couldn’t have been happier. It was the first bizarre surprise in a long, long series of novelties, quirks and clever moments that make up what is undoubtedly Larian’s greatest ever game.

The influence of the classics, Ultima VII, Baldur’s Gate II, they’re in there, but Original Sin is very much its own, unique grand adventure. Like an alchemical concoction, bright and experimental, it stands out even from its clear inspirations. And it makes all the Divinity games before it – a diverse bunch – seem like preparation.

Recalling how Divinity: Original Sin begins, humbly, produces a wry grin. Fresh off the boat, the two protagonists – Source Hunters (essentially members of an Inquisition dedicated to eradicating an apparently malevolent magical force) have a fairly simple task. A prominent member of the Cyseal council has been murdered in the seaside town, and the Source Hunters have been dispatched to solve the case and ensure there’s no “sourcery” involved, and if there is, to deal with it.

That goal is quickly blotted out by a dozen other threats and your typical fate of the world malarky, causing the Source Hunters to go off gallivanting across the realm (and time and space) in an effort to stop armageddon. The main narrative rarely deviates from tried and tested genre conventions, serving as a familiar backdrop that eases one into what is an extremely eccentric world.

It’s that world and its unusual denizens which gets its hooks in you, not the plot. Fast-talking impish historians that live at the end of time; love-sick felines that need to be set up on a date, an elemental realm in chaos, presided over by a fat snowman king – there are so many curiosities to be found in Rivellon that it’s a wonder heroes actually have the time to save the world.

I’m being a bit slapdash by saying “heroes”, because Source Hunters aren’t particularly heroic. The order itself seems fairly tyrannical, though ostensibly for good reason, and both protagonists can be friendly do-gooders, mercenary money grubbers or merciless cogs in the Source hunting machine.

Novelly, both of these not-really-heroes are equally important and influential. Lesser companions can join the party – two at the moment with more on the way – but the original two party members are both main characters. It’s a perfect setup for a co-op game, allowing each player to have their say and go off and do their own thing, never making one or the other feel like a minion or sidekick.

When playing alone, however, there are a few hiccups, but thankfully only when it comes to dialogue choices – though they can still have quite the impact. Both Source Hunters get a say when it comes to decisions both important and mundane. An NPC might ask for assistance, and while controlling Source Hunter 1 – whose default is a burly fellow named Roderick – I can agree to help this NPC out, because I’m just that sort of guy. But then my fellow Source Hunter gets to chime in, and she – Scarlett, if you choose the default character – might have other plans entirely. If she does, then a game of rock, paper, scissors must be played out, with the winner getting the final say.

Thanks to this system, I missed out on quite a few quests and rewards, and nothing positive comes out of this. The main issue is not that the AI can, on a whim, cut a player off from some of the game, but that it does so with such inconsistency. Sometimes Scarlett would be cruel and cold, other times she’s a hopeless romantic. It’s completely random. Indeed, it’s so random, that reloading the game and selecting a different dialogue option for Roderick could also lead to Scarlett choosing something different as well.

The solution I came across requires some hindsight. If Scarlett, or your second Source Hunter, is selected just before a conversation begins, you have control over what she says and what Roderick say, giving you the power to not only grow both characters’ personalities, but also ensuring that you don’t miss out on rewards or quests. The wonderful Richard Cobbett pointed out to me that you can also switch the AI off and have full control over both Source Hunters, which is significantly simpler than my method. It’s something not really explained in the game when choosing the AI personality.

Outside of dialogue, the party system is a complete triumph. Fiddling with the band of adventurers is a consistent delight. Original Sin doesn’t divulge all of its tricks, not even most of them, so new discoveries are frequent. Early on I decked Team Source Hunter out in the finest of accessories, filling their minds with new spells and abilities after I realised I could control the rest of my party even while I was in combat. NPCs have a field of view, so it was a simple matter of keeping the shopkeeper facing one character, deep in conversation, while the rest of the party robbed the poor fellow blind.

As I said earlier, Source Hunters are not heroes.

Everything that’s not nailed down can be looted, moved around and generally interacted with. It’s integral to the whole adventure. Through telekinesis, heavy objects can be moved and used to detonate traps, block holes that are spewing gas or flames or weight down buttons to open doors. These are just the most regular, dull uses for them, as I have no intention of diminishing the joy of experimentation.

The room Original Sin gives you to simply try new things and push the limits of the game’s rules and laws is also what drives it. Each new encounter, area and quest holds the promise of a unique oddity or serves as the inspiration for unconventional thinking.

Puzzles can be exceedingly clever, and even when they are simple, spanners are frequently thrown in the works. So it keeps you on your toes at all times. But beyond the puzzles, Original Sin continues to be a thinking person’s RPG. This is really emphasised by the combat system; a system that stands as one of the best in the genre.

It comes back to the party again, because the turn-based fights are all about synergising spells and abilities. While it’s possible to just build each character around abilities that seem interesting, battles go a lot smoother when each member of the party has been designed to fill in gaps and work in tandem with the rest of the group.

A large mob of enemies can be dealt with swiftly if one party member causes the heavens to open up and rain to pour down, while another takes advantage of the weather to strike with lightning attacks, the magic travelling through the water and bouncing between enemies. Those that aren’t killed or stunned could swiftly become the victim of ice magic, quickly freezing because they are already wet.

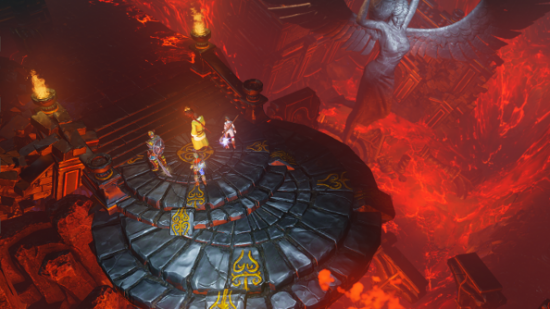

Strewn throughout these battlefields are all manner of environmental elements that can aid or hamper the party during battle: barrels of toxic chemicals, explosives even puddles or hurtling balls of molten rock spewing out of a volcano. It’s another thing that demands attention, never letting you simply cruise through a fight.

Fights aren’t about who hits hardest, fastest – they are won by the group that controls the field and manipulates the environment. And they can be big, these scraps. And long. Original Sin is not a game you can just play for half an hour and expect to get anywhere, as individual fights can go on for that long, and sometimes quite a bit longer.

The vivid magical effects and bold lighting can, at times, lead to battles feeling a little busy and bewildering. More annoying, the camera is inexplicably incapable of turning more than 180 degrees, which can add to the confusion, making it tricky to target or even see enemies with enough frequency so that it starts to grate. A minimap and a tactical mode that offers a bird-eyes view does alleviate this, however. [Update:In the comments, Fluttersnipe pointed out that there’s an option to turn on 360 degree camera movement. Larian warns that the game isn’t designed for that, though, so it might cause some minor problems.]

Throughout Original Sin, Larian has been able to fulfill its rather grand ambitions despite not having the gargantuan budget of RPG heavy hitters like BioWare or Bethesda. Even the isometric view and basic graphics – elevated, mind you, by excellent art and lighting – don’t feel like concessions, instead evoking the simpler looking but infinitely complex RPGs of the ‘90s.

So I can’t say that Larian has bitten off more than it can chew, not at all, but in one significant way, the studio wants to have its cake and eat it too. Rivellon is a big place. The massive surface areas and ancient sprawling dungeons take an age to explore, and such wanderings are encouraged. The lack of guidance inspires going off the beaten track and just looking for adventure.

But the game balance and Original Sin’s linear plot is juxtaposed to the freedom. In the first region, even leaving the town before level 5 invites death, and simply walking down a country road near the hub can lead the party of adventurers into a nest of enemies many levels higher. When even a single level can make a significant difference, this can be a mite frustrating.

The alternative isn’t handholding; a common sense approach to the escalation of threat is all that’s needed. The starting area really shouldn’t be surrounded by threats that could demolish new players.

I confess, though, that after licking my wounds when I fell foul of a high level enemy, I played more cautiously, employing stealth and scouting to find and assess threats before my main party reached them. I don’t think it’s too generous to assume that’s a design decision, I just think that it’s one that could have been tempered with a more organic progression.

The aforementioned linear plot has a much greater impact. There’s a specific route that needs to be taken, story-wise, and deviating from that – which can be done – causes all manner of confusion, with NPCs acting like you’ve done something you haven’t, and enemies suddenly jumping three levels higher. It’s a strictly linear story in a very non-linear world, and the two just don’t coexist very well because there’s no guidance, no way to tell which quest comes first.

Perhaps, in other games, I would have grown annoyed more frequently than I did, because any problems that Divinity: Original Sin has are surrounded and almost snuffed out by all the things it does, not just right, but phenomenally well.

Things that would normally be ancillary, at best, like an ability that lets you talk to animals are so fleshed out that I can’t imagine playing the game without them. I didn’t choose the Pet Pal perk as an example lightly, as it’s utter genius. Not only does it unlock a number of especially guffaw-worthy quests and absurd gags, there are puzzles I honestly don’t know if I could have completed without a walkthrough and paths I would have completely missed if it wasn’t for my ability to have a natter with a rat or shoot the breeze with a chicken.

When I play Divinity: Original Sin, I’m back in my parents’ study, gleefully skipping homework as I explore the vast city of Athkatla. I’m overstaying my welcome at a friend’s house, chatting to Lord British. And it’s not because the game is buying me with nostalgia, but because it’s able to evoke the same feelings: that delight from doing something crazy and watching it work, the surprise when an inanimate object starts talking to me and sends me on a portal-hopping quest across the world. There’s whimsy and excitement, and those things have become rare commodities. Yet Divinity: Original Sin is full of them.