id are an institution. The thing about institutions: they’re old. Now John Carmack has jumped ship to somewhere he can better pursue his undying dream for a holodeck, only artist Kevin Cloud remains of the original co-owners who once built Doom.

That’s not to say there’s no old guard left; creative director Tim Willits can claim two decades of service. Executive producer Marty Stratton signed up during the Quake years. The spirit carries on. But the development of Doom has necessarily been an act of interpretation, by a team who never got to wander around trade shows wearing one of John Romero’s legendary team t-shirts – the ones with ‘wrote it’ scrawled boastfully on the back.

The venerable 1993 original made our list of the best FPS games on PC.

Last year’s leaked video of an earlier, aborted Earth defence story made it clear: the game we’re getting is one of many possible Doom 4s. Stratton and his developers have made value judgements about what they think made Doom tick. What made it not so much a game as a sinkhole you happily fell into and bloodied your nose.

Onstage at Bethesda’s summer E3 show, Stratton spoke like a man who’d thrashed out the precepts of his game at length with a room full of fellow mega-fans, and become used to expressing them.

“We’ve been inspired by the way those original Doom games made us feel when we played them,” he said. “Although their premise was simple, they made us feel smart, and fast, and powerful.

“The foundation of any Doom experience past or present is unquestionably combat, that centered around three things: badass demons, big f-ing guns, and moving really, really fast.”

When I watch that first footage back, I see the fast. Doom 3’s high contrast aesthetic has been spliced with the raceway speed of the original Dooms. And I see the powerful, in the sub-bass punctuation of the shotgun. What I don’t see yet, in the corridors of id’s massive new Martian UAC facility, is the smart.

When John Romero made a Doom level, he played it constantly. He’d modify a room, or add something new, and then play it again. “A level,” he tweeted in September, “is 1000s of plays.”

The consequence of that approach? Tricksy, tightly intricate stages, dense with secrets, changing with every pushed button.

Consider Gotcha!, the Doom II map that sits two of the most powerful enemies of the game side-by-side: spiderdemon and cyberdemon. A gruelling encounter – except that the architecture of the room encourages players to view it as an arena, where they can deliberately draw one monster to fire on the other and sit back to watch the fireballs.

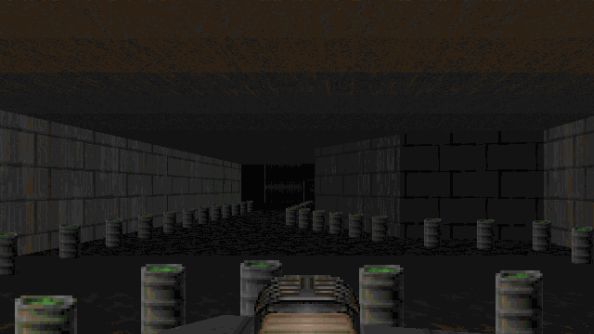

Think of the Catacombs, an apparent Agatha Christie mystery which had you pulling at lampstands to open priest holes. And remember Barrels o’ Fun, which planted you at the tip of a long corridor lined with toxic oil drums. As you edged tentatively forward, a lift revealed the bloated mancubus whose first shot would begin a chain of explosions. The barrels might as well have spelled it out: RUN.

One of the more underappreciated names in Doom history is that of Sandy Petersen, whose work ethic and devious designs landed him the coveted first level spot on Doom II ahead of Romero. About as seasoned as a game designer could be in 1993, he arrived at id having created the venerable Call of Cthulhu tabletop RPG a decade before.

Many of his areas began as Lovecraftian concepts, or role-playing dungeons he’d ventured through with pen and paper. As a horror story enthusiast, he delighted in stuffing his levels with rooms that looked safe and well-lit. Ominously so.

The term ‘monster closet’ was coined sneeringly in the years when games endlessly mimicked Doom’s surprise enemy placements. But removed from that context, it’s now easier to remember what was compelling about the traps. Every five minutes in Doom, there’s a moment where you can feel the eyes of a cackling designer on you.

Limitation was an inevitable part of early 3D shooters, and Doom made good use of it. Without a jump button, you’re nevertheless constantly forced to think vertically – when taking fire from an enemy on an unreachable balcony, or running the ramps that might allow you enough momentum to clear a chasm.

Doom never tries to hide its borders in the way contemporary shooters do, with falling debris and shouting squad leaders. Walls are walls, designed to be pushed against in case of a secret room or ammo depot. The space, such as it is, is all yours, and that geographical honesty is still striking.

Over the next few months, as Bethesda’s PR push picks up ahead of a 2016 release, id will try to tell you what Doom was all about. And that’s okay: since the beginning, id have always found new energy by feeding the egos of young talent, from Carmack to Willits to American McGee. Just remember that they’re fans, like us, accentuating the elements they love the most, revisiting the feelings that first led them into the industry. And let’s hope their level designers haven’t forgotten the twisting, twisted hellscapes Romero, Peterson and co. put together.