In Stanisław Lem’s classic sci-fi short story collection, The Cyberiad, there is a section called The Seven Sallies of Trurl and Klapaucius, two hyper-advanced robots who are so advanced they can conjure anything from technology. One of my favorite stories involves Trurl searching for a civilisation that has achieved the highest possible level of development (HPLD). To find such a civilisation, it decides it needs to find a ‘wonder’ or something that exists outside of rational explanation. In the end Trurl finds a cube-shaped star being orbited by a cube-shaped planet with the letters “HPLD” carved into it.

The planet’s inhabitants are all laying around doing nothing. Trurl wants to know why, so it builds a computer to simulate the entire universe, and after millions of attempts it gets an answer: they simply have nothing left to achieve.

When I play city-building games, and especially the recent variety of factory simulators like Factorio, Satisfactory, and Dyson Sphere Program, I often think of Trurl’s simulation. Each game has its own sort of end goal representing the highest possible level of development – a rocket, a space elevator, a Dyson sphere – but they all leave me feeling a little uneasy about their laser focus on efficiency above all else.

These games drop you on a planet with a smattering of resources and some kind of replicating device or construction tool. You harvest your landing craft (crashed or otherwise) and set about constructing your first mining tools to gather ore. Then you smelt the ore. Then you turn the refined metal into another tool. Then you mine some more, but this time it’s slightly more efficient.

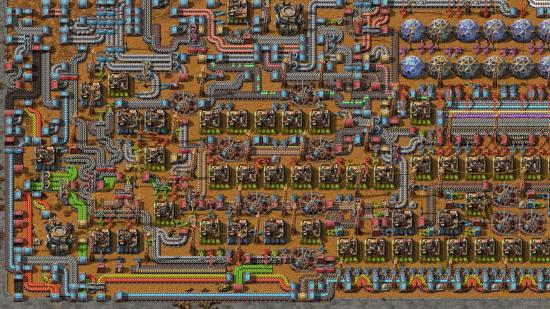

Eventually, you create tools and buildings that automate that process, allowing you to gather materials exponentially and pull yourself up to the next technological plateau, and this cycle continues until you’ve created a factory system that sprawls across the whole planet, a monument to manufacturing. Belching furnaces, whirring constructors, endless rows of meticulously placed conveyor belts, all digging and churning and transporting and dumping.

Every part of the process is dedicated to peak efficiency; a perfect clockwork machine slowly sucking resources out of the planet and turning them into more machines.

But what’s the cost? It feels increasingly gauche given the current state of the world. Their bare essence is one of strip mining a planet, engineering something smart from the materials, and moving on. It brings to mind the exact thing Lem was interrogating with the Seven Sallies: the golden age of sci-fi stereotype of the genius engineer who could solve anything with the application of proper science.

Meanwhile, we continue to mine our own planet’s precious metals in order to design and play pieces of entertainment which reflect our own dominant world mode. As the electricity usage required to generate the complex cryptographic codes required for cryptocurrency and cryptoart skyrockets, beyond even that of small countries, it’s interesting to play games that elide many of the consequences of mass industrialisation. At the very least, the science buildings in Dyson Sphere Project that hash out the unquantifiable resource of science should surely have more of an impact than the game portrays.

There are hundreds of videos and tutorials for Factorio and Satisfactory that teach you how to optimise your operation, making use of ‘bus’ configurations and varying speed conveyors to ensure everything is running perfectly. However, the resources in these games are functionally unlimited, and if your local pocket runs out you are encouraged to find more, slotting distant production into your main hub rather than considering sustainability.

When you watch plumes of acrid black smoke billow from your buildings in Satisfactory, there is no consequence. The game wears this on its sleeve with a lick of gallows humour, with the colonising FICSIT Corporation you work for proudly boasting “we do anything to find short-term solutions to long-term problems.” It cuts uncomfortably close to the bone.

Factorio does feature a pollution mechanic that punishes the player by sending swarms of aliens after their precious constructions. However, the player can either contain the pollution or outfit their base with enough firepower to repel the attacks. If anything, this approach leans even closer to the dynamics of resource exploitation in the real world, except it’s pissed off alien insectoids rather than innocent, displaced populations. It’s pretty wide of the mark, but it’s something.

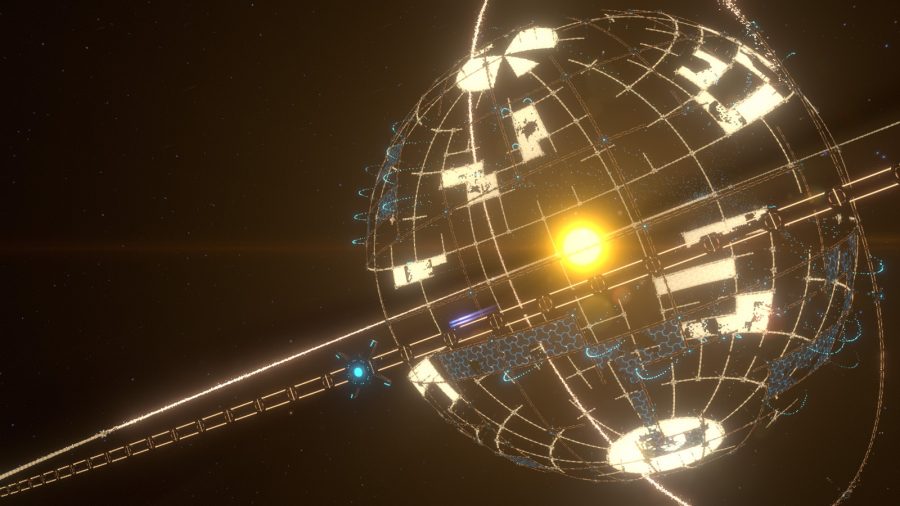

Dyson Sphere Program’s end goal is, at least, a Dyson sphere – a megastructure encompassing a solar body that effectively provides limitless energy. It’s a solution, but one that still requires the sacrifice of an entire solar system.

Ultimately, that such gaps are even noticeable is a testament to the skill of game developers to portray complex logistical puzzles. Games are an escapist fantasy, but the fantasy of industrialisation can only be so escapist when we exist on a planet that is being brought to the brink by our own progress.

Given that games can explore hypothetical scenarios and situations that are beyond us here on terra firma, perhaps it’s time for them to start poking and prodding at the efficacy of terminal industrialisation. There could be hard modes in factory games where avoiding material wastage is a benchmark of success.

A while back, I lamented at the lack of storytelling in city builders, and this is another interesting element that simulation games and industrial strategy games alike avoid. Can we imagine no solution beyond strip mining and mechanising our world, or are factory management games so appealing because they reflect our own ingenuity as a species? Either way, there’s an inconvenient truth at the heart of this enduring power fantasy, and games can do a lot more to tackle the subject.