If there’s one thing Dr. Jennifer Hazel wanted people to take away from her panel at GDC, it was that psychosis and psychopathy are not the same disorder. If there were two things, it’s that games have a tremendous capacity to reflect the struggles of people with mental health issues, and to break down the stereotypes and misinformation that have come alongside psychological disorders for years.

Hazel, founder of the gaming-focused mental health awareness organisation CheckPoint, says that games have often fallen into the traps of stigmatising mental illness – just as movies and television have. But while there are plenty of games set in creepy mental asylums or featuring loads of rampaging ‘psychos,’ at a panel titled ‘How to Represent Mental Illness in Games,’ Hazel showed six games that show mental illness accurately and empathetically – and explained how developers should learn from their example in the future.

An organisation called Mindframe presents a set of guidelines for general media coverage of mental illness, which Hazel adapts into a set of recommendations for game developers: use accurate language to talk about mental illness; accurately portray symptoms; know your purpose when you’re using mental illness; avoid stereotypes; show empathy toward people suffering from mental health issues; and show people giving – and receiving – support.

In Stardew Valley, players who develop a relationship with Shane discover that he’s struggling with depression. Shane’s comments about feeling helpless accurately mark the symptoms of depression, and a nearly suicidal event has you take Shane to the town doctor – who, in turn, recommends counseling as treatment. Shane gets support, and players empathise with his struggles thanks to how he’s portrayed.

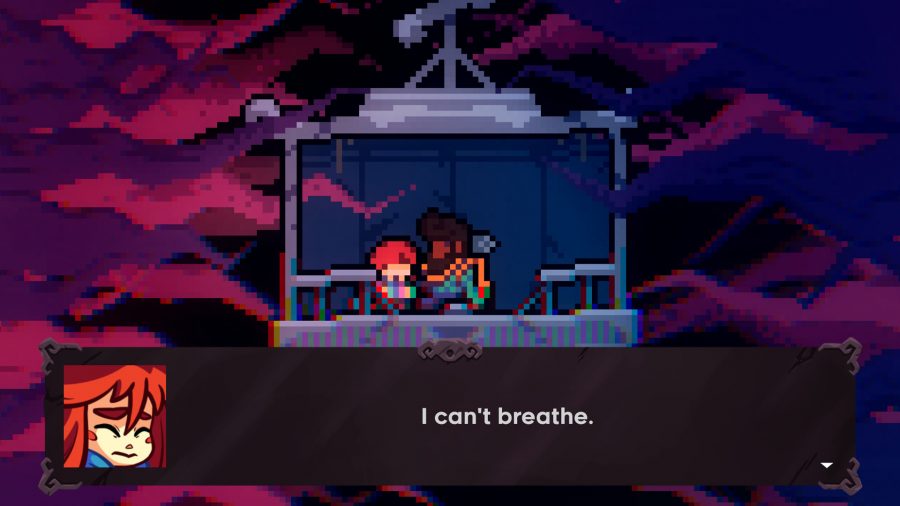

Celeste’s efforts to turn the platformer into a metaphor for anxiety are now well-known, but here Hazel focuses on one specific scene: the gondola ride. Here, the protagonist Madeline suffers a panic attack – accurately described by another character in the game – and then she learns a breathing exercise to help cope. That exercise turns into a proper gameplay mechanic, and it even becomes a transferable skill for players who might suffer from anxiety.

Hellblade: Senua’s Sacrifice – which Hazel calls “my game of the decade” – is about a woman suffering from psychosis, one of the most misunderstood mental health conditions. But Hellblade shows psychosis accurately, from the hallucinatory dialogue that accompanies Senua throughout the game to the specific ‘delusion of nihilism’ where she – and by extension, the player – believes that the creeping Dark Rot will engulf her after too many failures.

Games like The Last of Us and last year’s God of War deal with mental health in more traditional ways, through plot and character development – but both games show the effects of trauma and PTSD in nuanced ways. In the wake of his wife’s death, Kratos grows more detached, except when he lashes out in anger. Yet we’re given the chance to sympathise with him thanks to characters like the Witch, who’ve had similar traumas over loss in the past and explain – both for the sake of other characters and the audience – what’s happening with Kratos.

Joel’s relationship with Ellie in The Last of Us is driven by the traumatic loss of his daughter, which in turn drives the plot of the entire game. Joel tries to avoid staying with Ellie because she’s too much of a reminder of who he’s lost – or, in more clinical terms, he’s avoiding the triggers of his trauma. Both Last of Us and God of War also avoid the common stereotypes of PTSD. While there’s violence involved for both Joel and Kratos, the brunt of why they’re suffering is loss – it’s not the stereotypical war trauma most commonly associated with PTSD.

Hazel points to Chloe in Life is Strange as a strong example of borderline personality disorder, citing her black and white thinking, emotional instability, impulsive behaviour, and fear of abandonment. Yet there are sympathetic causes for her symptoms, and the game’s emphasis on relationships and character development at the core of its plot mean players are able to empathise with her.

So why does any of this matter? Studies vary on exactly how prevalent mental health issues are but the range is often shown as 25%-50% of the population – a massive number of people at either end of the scale. Two-thirds of people who suffer from mental health issues will never seek treatment, and that’s because those issues are so heavily stigmatised – in part by movies, television, and games.

Read more: Celeste is one of the best games of 2018

But the titles Hazel showcased at this panel show that games can just as easily provide realistic, sympathetic portrayal of mental health problems – and those can help players empathise with others who suffer from those issues, or recognise them in themselves and seek treatment. It may seem like too much for one game to change the world, but a line of games following in the footsteps of Celeste, Hellblade, and others can promote understanding – which, in turn, means nothing less than saving lives.