What’s up, PC gamers! How about Apple’s RAM prices though, right? No. Sure. Tough crowd. But I only bring it up as a prime example of a practice called price discrimination.

When a business brings their product to market they don’t actually know how much you’d be prepared to pay for it, so they make their best guess. And then they tack on optional extras, which you buy because you were prepared to spend more on the original product than its retail price. Or you don’t, and some other schmuck does. The bottom line’s the same: people who would have bought the product for a higher RRP still wind up paying more.

Apple’s exorbitant RAM prices are price discrimination 101. But, to bring things circuitously back to the headline, this example also neatly describes the games-as-a-service model. For almost a decade now, game publishers wanted you to keep playing and playing their new title, please. For ages. They do so because the longer you keep playing, the greater the probability you’ll spend more money on it. You can call it something else, like a ‘player-driven ecosystem’, dress it up in a limited edition seasonal skin and trot it out onto an E3 stage, but that’s really all service games amount to. Spending more money on extra bits of the same game.

The benefits for us down at consumer level, comrades, have been quantifiable: people seem to quite like Destiny 2, for example.

More than that, this model held studios accountable when their initial release wasn’t up to standard. Games like No Man’s Sky, Star Wars Battlefront 2, and For Honor had little choice but to update and update until people liked them and wanted to play them, because they were supposed to hold an audience for years.

But service games are a lot less popular with people who play games than with people who make them. Because we still don’t particularly like buying DLC, or following narratives without much plot or conclusion because they take place in shared worlds. We’re not enamoured by the focus-grouped art or the by-the-numbers design that we find in games intended to draw in broad audiences for a long time. Fundamentally, we miss Thief: The Dark Project. Ahem, I miss Thief: The Dark Project.

Top picks: Here are the best PC games to play right now

How might a single-player game like the aforementioned Looking Glass meisterwerk, with an untested setting and a fresh combat style at its core, make it to storefronts today?

Easy. Just double the price of games.

And before you hoist me up on a noose next to Don Blankenship, let me give you a little more to work with. Videogame prices haven’t increased in line with inflation over the last twenty years. Baldur’s Gate II cost £30 in 2001 (and I seem to remember it having about 40 discs in the box, too). Most console games cost between £40-£50 at launch at that time. By the Bank of England’s reckoning, a PC game at the same price point should cost £50.74 / $69.76 in 2021 to match inflation, and those pricier £40 console games would set you back £67.66 / $93.04 – and that’s just to keep up with inflation.

Sony’s already at it with PS5 game prices, now approaching £70 for us here in the UK. The company’s suits have cited inflation and increased game production costs for that price hike.

And they’re not wrong. The production cost of triple-A games has increased fairly linearly over that same period dating back to 2001. That’s even considering the absence of mechanical costs now – you don’t go and buy a disc in a box with a man frowning on the front of it anymore, but that digital copy still costs developers more to realise. The people making the big games are spending more money to get less money from you. On those grounds it’s not unreasonable to charge more for a game.

And it also lessens the necessity to rely on a service games model to recoup expenses. Which means: hello weird single-player games with a budget behind them. They might be niche, they might appeal to a very vocal but very small group who haven’t gone a day without typing ‘immersive sim’ somewhere since 2000, but the few sales they make are worth double.

The same, of course, goes for all the other flavours of weird we’ve forgotten about in recent years. It’s been so long since we had a Spore or a Giants: Citizen Kabuto to marvel over. Higher initial outlays means less risk aversion. A higher price point is one way to bring creativity – real honest-to-goodness new ideas with financial support – back into the industry once more.

And although I’m talking about the old model of game production, with publisher relationships and upfront budgets, I’m not limiting this theoretical price hike to the Valves and Rockstars. With fewer upfront development costs, indie gaming has the ability to self-govern its pricing, although creators often work unpaid outside of their day job so lower budget doesn’t equate to lower cost. They’re making a huge investment in their project, and if they double the price of their finished product, their return on investment suddenly looks a lot nicer.

Hold on, though. We don’t want to position games as the digital caviar upon which only the affluent feast, do we? And doubling the financial barrier for entry certainly seems like it might be doing that.

But then, what’s our current industry doing, by comparison? Giving the unsalted, unflavoured game to the masses and keeping the treats behind a velvet rope for the bourgeois to enjoy? Facetiousness aside, that economic model’s stuck around because sufficient numbers have kept feeding it, buying the skins and the expansions and the season passes. It doesn’t feel especially egalitarian either.

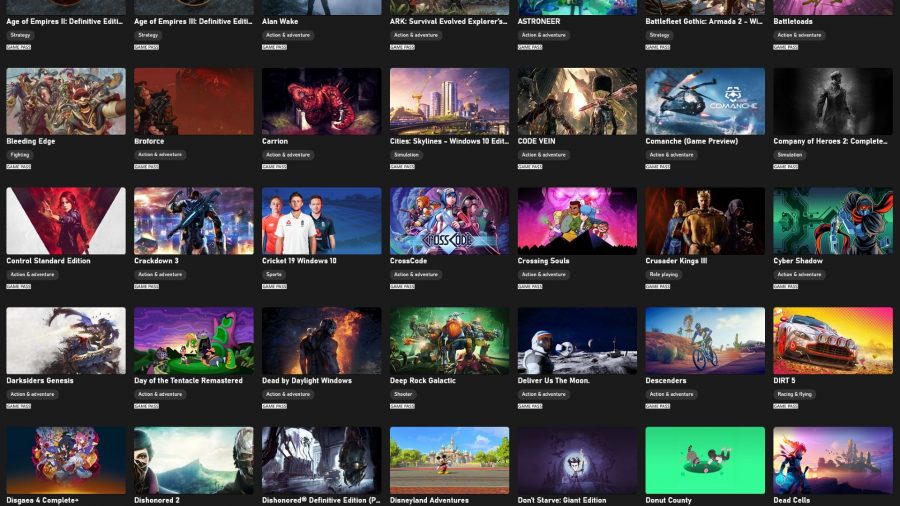

Subscription passes seem to offer another way. What if a Netflix-like entity ate the cost of modern game development via a license fee, and then absorbed it by virtue of its massive user base paying an affordable monthly fee?

Microsoft already has its hand in with Game Pass, as has the aforementioned purveyor of £70 games, Sony. But the latter’s Jim Ryan was quick to temper attitudes about the subscription model’s sustainability in an interview with Eurogamer: “We are not going to go down the road of putting new-release titles into a subscription model. These games cost many millions of dollars, well over $100 million, to develop. We just don’t see that as sustainable.”.

In that same Eurogamer piece, industry analyst Daniel Ahmad explains that subscription pass monthly fees are only cheap now because those services are trying to hook us all in: Xbox is “very much in a user acquisition stage”, which is why we’re still seeing the ludicrously generous £1-for-3-months offers aiming to bring people on board. Once those people are on board, other subscriptions tell us that they’re likely to stick around.

So perhaps we’re back to paying for the art we care about. Nobody should tell you how to spend your money – but we see between 4,000-10,000 advertisements per day which do exactly that. Perhaps that’s why each of us has a pile of shame in Steam, essentially a measure of our gaming wastefulness, which in turn suggests that an industry price increase might not deny us entry based on our means. We might just be that touch more discerning.

‘What if?’ is PCGamesN’s new regular feature series. Check back every Saturday for more hypotheticals, from thoughtful speculation about actually-plausible industry developments, to dream crossovers, to nonsense like Half-Life 3 happening.