“How are we going to allow the player to fully, interactively inhabit a role in this immersive space that is non-linear?,” Steve Gaynor asks us. He has the luxury of doing so rhetorically, having worked over the details at length with his four-strong team in Portland during the development of Gone Home – a game about rifling through an empty house to discover that it’s brimming with life.

The kind of studios that have asked this question before are mostly dead and buried. Looking Glass Studios met an ignoble demise at the turn of the century amid cardboard boxes and blank plaster walls unbothered by award cabinets. Deus Ex originators Ion Storm Austin took custody of their charge, Thief, but followed soon after. And great recent hope 2K Marin – founded by the level designer behind Thief: Deadly Shadows’ infamous Cradle and BioShock’s Fort Frolic, Jordan Thomas – succumbed to the very vocal critics of their first-person XCOM before folding themselves.

“We decided that we wanted to have that human connection of the voice, and have Sam telling her story in her own words,” said Gaynor.

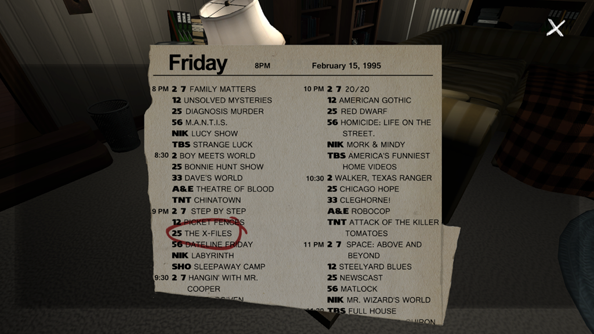

Sam’s missives provide the only human sounds in the game aside from the Riot grrrl tapes found in the house’s various nooks and hideaways. But beyond that crucial point of empathy, the diaries also offer a structural core, a tacit contract with the player: “If you find all the pieces, it’s told to you.”

“And then for everything else [it’s] along a spectrum,” said Gaynor. “The further away that core story is, chronologically or character-wise, the more work the player has to do to add it up and put it together themselves.

“So, like, the parent’s story is still very calculable, if you’re paying attention, but it still requires you to say ‘Oh, the concert ticket and the poster in Mom’s room and the date on the calendar’, and you need to pay attention to make those connections yourself.

“The story of the game is essentially like a puzzle that you’re putting back together.”

Gone Home has that loose narrative structure in common with Dishonored – the other notable contemporary proponent of the immersive sim genre Looking Glass and Ion Storm defined. But where Dishonored pulls with it many of the trappings of Thief and Deus Ex, Fullbright sought to reduce their game to its barest elements.

“I feel like the idea of an immersive sim has built up and accreted a lot of elements over time,” Gaynor said. “Where’s it’s like now there’s going to be powers and weapons and upgradeable abilities and loot and an economy to buy stuff, plus the overall open-ended level structure that you can explore and so forth, and environmental storytelling and everything.

“Part of our strategy was to say, ‘How much of that can you remove and still deliver what I feel are the core tenets of our design philosophy?’.”

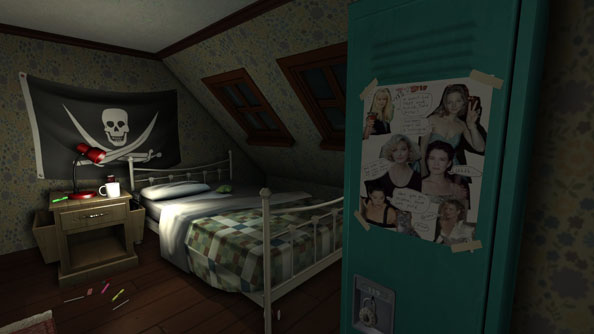

The revision started with protagonist Katie. The dearth of mirrors in the Greenbriar household won’t stop us from noticing that she’s no test-tube cyberninja – merely a “normal person” who comes to a house she doesn’t know to see the people she knows best.

That fictional conceit informed all of the game’s mechanics. Where JC Denton hurls whatever he’s holding against the wall opposite by default, a respectful Katie is offered a gentle prompt to ‘put back’.

“We say you can open all the drawers and cabinets and you can read everything and look at everything, and you can actually have that relationship with the environment that allows you to pick up a tiny scrap of paper and actually get value out of it,” said Gaynor. “Because in that role, that’s what you would want to do and be able to do.”

Which makes it all the more surprising when Gone Home throws up a moment that’s straight outta Rapture. Fumbling for the bathroom light, you illuminate the scene, as you have so many others around the house – and see that the tub is splashed blood red. You wait for the spiralling violin score, but it doesn’t come. Instead, there by the taps is a half-empty bottle of scarlet hair-dye.

You see: while Katie is respectful as can be, Fullbright like to make fun of their forefathers.

“There are a lot of environmental storytelling tropes and clichés that have developed,” laughs Gaynor. “Like a blood splatter next to a guy with a pistol sitting next to him – ‘Oh, this guy shot himself’. You’ve seen that in every game, and messages scrawled on the wall in whatever medium you want, whether it be paint or ink or blood or whatever. I saw the scene, the stuff here gave me 75% of the story, but then they had to put really big words there to tell me what it’s supposed to mean, right?”

Immersive sim players have been trained to expect horror. And beyond the bathroom, Gone Home repeats its subversion on a grand scale (as grand as it gets in a space no more than 100 metres across, anyway) – letting its tension give way to something ultimately far more vital: love.

Fullbright made a tactical decision to maintain tension in the early part of the game using the semantics of horror – but banked on players becoming invested enough in Sam and Lonnie that their romance would drive exploration long past the time that initial impression wore off.

“By the back half of the game you’re no longer playing because you want to find out when the horror thing is finally going to happen,” explained Gaynor, “but because you’re actually invested in the characters and their story for the people that they are.”

The result of that switch is a palpable wash of relief at the conclusion of the game, when a story about Sam’s apparent death instead turns out to be a heartwarming romcom with an implied Four Weddings kiss-in-the-rain ending. It’s possibly the first of its kind in the medium, and Gaynor is proud to have written it.

“I’m glad that could be where we ended up because I would much rather be able to give people that feeling of relief than just to follow through with, ‘I feel like something horrible is going to happen – oh, it did!’,” he said.

“I think that there are very, very few games that allow you to have that feeling of relief and catharsis, and, ‘Oh man, I was worried something bad was going to happen and now I’m so happy that it didn’t’.

“I think that’s actually really rare in games, and I’m much more proud of being able to give people that feeling than just to lean on the heaviness and darkness that I think is actually an easier place to go to in a lot of ways.”

Fullbright chose life for Sam. Gone Home is no postmortem. And their own future beats as hard as that Heavens to Betsy soundtrack.

Oculus Rift support is still under consideration – and though they’re grateful for the array of fan translations that’ve sprung up in the months since Gone Home’s release, Fullbright are pondering an official patch.

And after that? They’ll tell one of the “hundred more stories” Gaynor believes are waiting to be told using Gone Home’s interactive model. Just as they reduced the immersive sim to its barest elemental potential and built in back up again, they’ll do the same to Gone Home.

“I think that the base that we’ve built – it’s so broadly useful, you know?”, he said. “I think there’s a lot of different ways that you could explore further from that base and end up somewhere new and interesting.”