Describing L.A. Noire as a war game initially seems ludicrous. You play as a detective, in Los Angeles, in 1947 – you are hardly on the frontlines. America’s campaign in the Pacific is shown repeatedly in flashbacks, and several of L.A. Noire’s central characters are ex-soldiers, but war in videogames typically means big battles and lots of shooting and explosions. Famously, it is a genre uninterested in subtlety, and so L.A. Noire’s dialogue-heavy forensic drama doesn’t immediately appear to qualify.

Can’t wait for more Rockstar games on PC? Check out everything we know about Red Dead Redemption 2.

But look again. Watch L.A. Noire’s preposterously animated faces, wait for one of its theatrical tics, and then press 2 to ‘Doubt’. From Cole Phelps’ rocky relationship with the rest of the LAPD, to the illegal Army-issue morphine syrettes at the centre of so many of his cases, the Second World War is everywhere in L.A. Noire. Its clownish interrogation sequences and (for a game published by Rockstar) comparative lack of exploration and size, made it seem unusual on release; L.A. Noire was hardly the open-world crime caper fans of Rockstar and Team Bondi might have expected.

However, in retrospect of games like Spec Ops: The Line, Wolfenstein: The New Order, and Mafia 3 – which have helped make popular the idea of conflicted characters who question violence, even in big shooters – L.A. Noire looks practically pioneering. If games generally contend that victory in war is absolute, and that, so long as you do win, everything will be alright, L.A. Noire excavates the conflicts that occur within people and their country after they return home. Its depictions of men, families, indeed a whole society inflicted by war are fittingly hard to determine and require investigation.

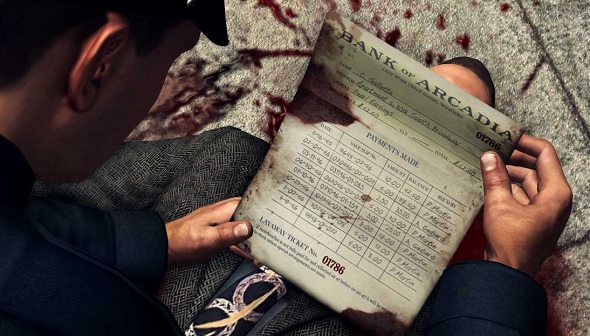

We solve murders, drug deals, and arsons, but throughout L.A. Noire a much more encompassing crime is being committed. The Los Angeles city fathers – financial brokers, real-estate developers, and local politicians – have connived a scheme whereby they sell substandard housing to returning war veterans, burn it down, payout the insurance, and then repurchase the land at a cut price, thus paving the route for a new multi-lane freeway. On the surface, Cole’s job is combating L.A. street crime, one autopsied body after another; in actuality, with each closed case we unfurl a conspiracy and corruption rooted in American post-war identity.

In 1947, the United States had just defeated fascism. With the might of its sheer production – its manpower, and mass-produced tanks, planes, and weapons – the US demonstrated that its core values, like democracy and liberty, can prevail globally. “This is the start of the American Century,” Phelps reflects in the game, from the deck of the battle cruiser carrying him to Japan. “America can rule the world after we win this war.” But American rule, of the kind founded on ideals like expansion and capitalism, is shown in L.A. Noire to be inherently corruptible. The people with the most money, like the ones spearheading the freeway project, are actually the most crooked.

The propagation of American power – building a big road that will connect cities and businesses – is predicated on lies. Even the American values that seem the most sincere and altruistic are thrown into question: taking care of the poor and the needy, i.e. injured and moneyless war veterans, is actually just part of a ploy to make the rich richer and the powerful, well, more powerful. In L.A. Noire, the standard bearers for American ideology – the politicians, investors, and humanitarians – are variously avaricious. By association, America’s victory in World War II becomes mitigated. If men and practises like these prosper in the nation’s post-war culture, we’re made to question whether its assumption of global power and the beginning of its century can really be celebrated. Typically in videogames, victory in war means the establishment, or re-establishment, of a status quo. In L.A. Noire, like a gigantic freeway built on dirty money, it paves the way for unbridled American agency.

At a more intimate level, the individual ex-soldiers in L.A. Noire, since returning from war, are either internally conflicted or outright ruined. Most prominently, Ira Hogeboom, a former flamethrower operator, suffers from hallucinations and requires constant psychiatric care. In further reference to a corrupt but hidden American system, it is Hogeboom’s own doctor, ostensibly a model for self-sacrifice and good morals, who actually recruits and uses Hogeboom to burn down the other veterans’ houses. Elsewhere, army medic Courtney Sheldon becomes a drug dealer and is eventually murdered. After getting embroiled in crime, Marine corpsmen Eddie McGoldrick and Walter Beckett are killed also. The deaths of these characters underpins L.A. Noire’s central assertion: that victory in war doesn’t equate to indubitable prosperity and wellness from then on. In Cole Phelps himself, the game personifies this ambivalence, this near agnosticism, regarding post-war glory.

Related: the best World War 2 games on PC

A clean-cut, officious, sober war hero with a good job and model family, Phelps on the surface is the poster boy for the New America. He encapsulates precisely the combination of righteousness and work ethic that won his country the war. Later, however, Phelps cheats on his wife. His heroics at Okinawa are found to be greatly exaggerated and his fellow Marines regard him as self-serving and opportunistic. As if to suggest there are two sides to every story, person, and maybe even military victory, in a near reflection of his earlier “American century” scene, Phelps’ comrades sit aboard their own battle cruiser and call him a “phony bastard.” He lies about loving his wife. He lies about his record in the war. Phelps’ diligence and piety start to seem less genuine, more like an effort to cover something up: he is flawed, mercenary, and full of weaknesses, and tries to disguise it using traditional American success and exaggerated war glamour. In short, he embodies L.A. Noire’s depiction of a post-World War II United States.

By embellishing his heroism in the Pacific, Phelps is able to ascend through the LAPD. By defrauding returning veterans, the Los Angeles power players are able to build their freeway and make their money. And by convincingly winning the war, America is free to capitalise and establish its century. From bottom to top, L.A. Noire shows how a war victory is exploited for immoral – or at least questionable – gains. Not only is the game engaged in big questions of politics and history, it represents them at national, institutional, and then personal levels – by depicting Phelps as struggling to keep up with his country’s post-WWII ideas. It tries to show how societies, eras, and, of course, wars directly affect people.

Concerned with the insides of its characters’ heads, and looking at America with a close, examining perspective, it seems almost poetical that L.A. Noire should be remastered for virtual reality. In literal and metaphorical ways, it is a game about looking and seeing; appealing directly, technologically to players’ eyes is fitting. But, regardless of contemporary gadgets, L.A. Noire still feels fresh today. Sometimes games are outright uninterested in politics or people. Other times, they are engaged only with these topics, at a cool, almost orbital level.

Popular games like BioShock: Infinite, Deus Ex: Mankind Divided, and Nier: Automata do have points to make about, say, America, big business, and peer pressure, but they do so through written lore and explanatory set-pieces, not so much through credible and human-sounding conversations. Dialogue in L.A. Noire is not always convincing, but in the personal struggles of Phelps, Sheldon, et al, lies an allegory for their country’s nuances and problems. As much as these characters struggle to be model soldiers returning from war, settling back into civilian life, L.A. Noire’s America does not live up to the promise of its ostensible, immaculate victory in the Second World War.