Straddling the border between Poland and Belarus is the Białowieża Forest. Stretching on for 3,000km², this ancient natural wonder is one of the largest remaining parts of the primeval land that once peppered the entirety of the European Plain. Home to a unique ecology, the forest is protected as a national park and UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Related: the best Minecraft seeds.

However, around 150,000 acres of the forest sits outside that protective status. Almost half of the trees in the entire forest are dead, eaten away by infestation from an insect called the spruce bark beetle. This infestation was used by the Polish government as justification to log down the forest on the edges of the UNESCO-protected area. Despite a court order from the European Court of Justice, and pressure from activist groups such as Greenpeace, the logging continued for well over a year.

The science behind this justification was not sound. When a tree dies, the beetle moves on to a new one – therefore logging the dead trees does nothing to halt the issue. Not only that, but the deaths of the forest’s trees are a part of its ecosystem, the dead wood providing nutrients for species of fungi and insects endemic to the area. In fact, the forest’s UNESCO status was initially granted because of these primeval processes taking place – this cycle of life and death. The spruce bark beetle is a part of that natural process; eventually, predator populations will grow and animals will feed on the beetle, reducing their numbers.

Fortunately, for now, logging has been halted, thanks to the combined efforts of Greenpeace, other activists, pressure from Europe, and a Polish team of advertising specialists who leveraged the reach and educational value of a little game called Minecraft.

“I came back to Warsaw last year, in autumn,” senior advertising copywriter Wojtek Voiteque Kowalik tells me. “This was the time this whole political shift happened in Poland. It struck me that Europe’s last lowland primeval forest, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, a national park, was being logged down. I grew up around nature, so I’m emotionally connected – I remember where the forest used to grow, and where it doesn’t exist now.

“Białowieża Forest is unique on a world scale – in terms of the natural processes taking place there, it’s [as precious] as the Niagara Falls or Mt. Fuji. It’s not as well promoted around the world, so many don’t know it. Even the name, it is almost impossible for a non-Polish speaking person to pronounce. There are a lot of obstacles from it entering this massive consciousness, so we decided to call up Greenpeace and offer them a hand.”

Kowalik has worked in advertising for a long time, but he has always stuck to a single principle: advertising in the 21st century should at least attempt to solve problems. He believes brands should identify global issues that fall into their field, then attempt to fix them. With that goal, he takes on at least one pro-bono project every year. In 2017, that project was to work with Greenpeace to help halt the logging at Białowieża Forest. Instead of standing on the frontlines with the activists risking their lives blocking machinery, Kowalik and his team leveraged their skills in communication to kick off a campaign involving one of the most popular videogames in the world.

“We were talking about gaming and someone said, ‘Actually, Minecraft isn’t a videogame anymore, it’s a social media. It’s more than a game’,” Kowalik remembers. “It’s a community of around 87 million active players over the world. It’s a game that brings people together. A lot of communities set up their own servers for whole neighbourhoods. When I was growing up in a small town, we had this arcade – there was always a kid with one coin who could beat the whole game. Other kids would watch them playing, and this is what’s happening with Twitch and YouTube now.”

Minecraft is even bigger than its massive user base lets on due to its popularity across streaming platforms and social media. As well as the people playing the game, millions are watching streamers play, put together tutorials, or show off custom maps. Kowalik and his team looked at these numbers and decided what his team should do: they were going to create a 1:1 replication of the Białowieża Forest in Minecraft, approach some of Poland’s biggest livestreamers, and attempt to educate kids on the importance of this natural space via the game.

“We got in touch with a company from Denmark, called GeoBoxers,” Kowalik explains. “They made a copy of Denmark on a 1:1 scale in Minecraft. We called them up knowing they are too expensive… but you see, advertising for good and great ideas are kind of contagious… they loved it, they were in.”

That being the case, a deal was struck so that Kowalik and his team would do the preparation work while GeoBoxers would go on to create the Minecraft world. The preparation stage required Kowalik to use satellite imagery and cartography software to trace every single feature of the forest by hand.

“Even the smallest stream and grass fields, down to 20 square meters, had to be drawn by hand and put into separate layers,” Kowalik continues. “It took me over six weeks of working at night. At the end of it, I had this file full of tens-of-thousands of features over this 700 square-kilometer area.”

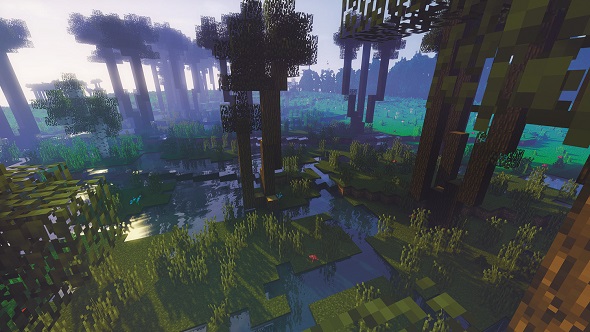

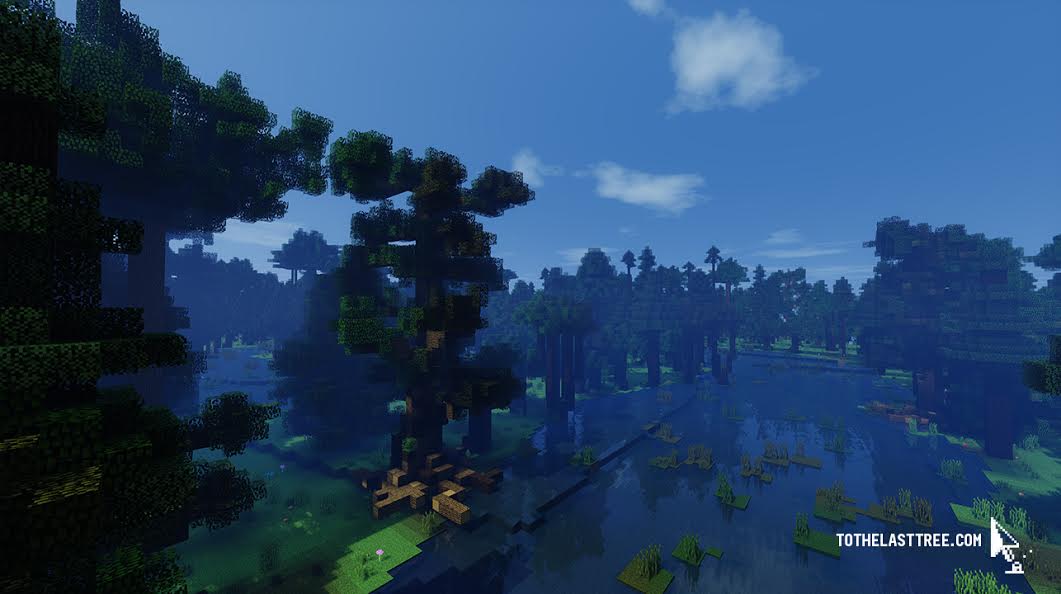

The tracing had to be perfect, because it had to match up with what appeared on the topographic model. If a river exists in one layer then there needs to be a riverbed in another. Białowieża Forest also has areas where only specific trees grow, where trees grow in a certain shape, to a certain height, fighting other trees for dominance as they battle to reach the sun’s rays. Areas such as swampland could not contain oak trees because oaks are too heavy for the soggy ground. Where there is a stream, the grass floor of the forest glows with a different shade of green, thriving on the nutrients the water provides. There was a lot to take into consideration.

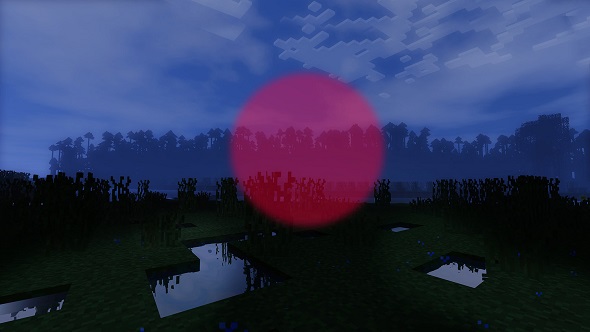

“It took over three months in just production,” Kowalik says. “It took [GeoBoxers] a while as well, because they wanted to do it perfectly. We sent them thousands of photographs of the trees, because they look different than anywhere else in the world – oaks are much taller and their branches reach higher as well, because they need to reach the sunlight. Everything needed to reflect that. Plus, there needed to be a lot of deadwood in there, trees lying on their sides. A biome like this doesn’t exist in Minecraft. They did fantastic work. I already knew the features of the real maps. I could actually go and visit the places I knew by eye. The moment you see it is pretty much exactly the same is a moment worth living for.”

The team then put together a video of the creation and roped in Krystyną Czubówną, the Polish David Attenborough, to provide voiceover work for this faux nature documentary. On top of that, 12 of Poland’s most prolific landscape photographers helped out for free, coming into the offices and using Minecraft’s tools to take stunning shots of this virtual environment.

The team then put together a video of the creation and roped in Krystyną Czubówną, the Polish David Attenborough, to provide voiceover work for this faux nature documentary. On top of that, 12 of Poland’s most prolific landscape photographers helped out for free, coming into the offices and using Minecraft’s tools to take stunning shots of this virtual environment.

“They expected to be briefed on going to the Białowieża Forest to do some shots, but we sat them in front of a computer and showed them Białowieża Forest in Minecraft,” Kowalik laughs. “They were like, ‘What the hell is this?’. We told them this was an exact copy of the forest and they have to choose their landscape and take a screenshot. After the initial [worries], they started learning the commands, playing with the shaders, with light, with time of day, they started flying around the map, and they got so into it. They produced some amazing work. So we put word online of a big group show, 12 of the biggest photographers – an unprecedented thing in Polish art. A lot of people came to the exhibition and they didn’t know they were going to see Minecraft screenshots, but everyone loved it.”

The 19GB map became an instant hit, its popularity bolstered by a team of famous Polish streamers and YouTube stars who helped get word out. Securing the help of Gimper, one of Poland’s biggest livestreamers, the advertisers set up a series of educational streams. Throughout, they hinted that something special would happen on an upcoming Sunday, during the school summer holidays. When the day came, there were over 10,000 people watching concurrently – kids, learning about nature, outside of school time. When the viewing numbers hit their peak, the big moment was revealed: Gimper loaded into the massive map and all the trees were gone.

“[Stripping the trees out] was a thing we considered kinda risky,” Kowalik recalls. “Showing people that the forest was cut down might have sent a bad message, but we decided to untwist it a bit with a Twitch livestream with Gimper. We basically prepared the kids, made them wait. They were really anticipating that an event was going to happen that Sunday. The moment Gimper logged in with a few more livestreamers, they didn’t know what they were going to see. One moderator knew what was happening, so she had a script and she was reading some facts about the forest, and she was guiding Gimper. The idea was that, once he logged in, all seven million trees, except one, were chopped down. The map was filled with seven million tree stumps.”

Gimper had one task: to find the last tree standing. After a lengthy stream, he finally found it and was teleported to the original version of the map as a reward. The idea was to empower the children watching, to show that people can make a big change to the world when we pull together – a symbol of hope.

“When these kids are grown up and they go to vote, hopefully environment is not going to be a thing of Left or Right – it’s going to be a crucial part included in the policy of whatever party they are voting for,” Kowalik says. “Taking the environment as seriously as education or human rights is the mark of a major democracy. With educational campaigns like this – I don’t want to sound like we’ve changed the world – but we have helped a little bit. If there were more campaigns like this, more people would be aware of how serious it is, and how these issues are often stripped down to the most basic political weaponry – to get power, to earn money, or just for those who happen to be in the wrong.

“When the Conservatives took over, nobody really expected they would start chopping down forests. Something has shifted badly. Then again, there are cycles in politics. When Liberals were ruling for the last ten or 15 years, a lot of Conservative people were largely overlooked and ridiculed. We might disagree with them, but they have a right to think this way. That’s why, after some time, they mobilised and elected their own politicians. In Poland, being a supporter of the environment has been a [concern] of the Left. If you are pro-environment, you are a leftist, you are a hippy. We noticed that a lot of people are supporting the Polish government logging the forest, just because they don’t want to be connected to the leftists. The scientific community supports leaving the forest alone. We wanted to reach out to kids. They don’t have this polarised view of reality yet. We wanted to create a neutral ground.”

Perhaps we will see a political shift for the better when the current generation of children grow into adults, and a better, more optimistic future will be born. The cycle can begin anew, just like the natural processes of the primeval forest.

Head to tothelasttree.com to see their work.