My love of watching mechs, robots and unmanned vehicles battling it out for my entertainment either stems from my for my abiding fear of artificial intelligence (thanks, HAL, Skynet and AM) or from the fact that beneath my surly demeanor, I’m actually a big softy and I long for the day when it will be robots rather than squishy humans – possibly with family and chums back home – fighting and being destroyed.

Planetary Annihilation’s brand of Total Annihilation and Supreme Commander strategy has been keeping me entertained for some time, with a never ending supply of mechanical wars on an interplanetary scale holding my attention. The recent move to beta has expanded the war into a fight for the solar system, spreading it across multiple worlds, but has this been enough to make it worth your time?

A battle in this aggressive RTS is a relentless drive forward. If you’ve stopped building – units, factories or defences – then something is terribly wrong and your lovely base is probably going to end up becoming a series of unsightly craters.

From the moment you place that first metal extractor or power plant, until you either destroy your dastardly foes or go out in a nuclear explosion, you must never cease in your tireless pursuit to cover the planet in structures and weapon-clad machines. You’ve just constructed a vehicle factory? Build another, speed up production, feed the war machine. Every factory – split into aircraft, land vehicle, bot and naval factories – can also construct a fabrication unit, which can help the commander construct more buildings, or strike out on its own and manufacture solo projects.

You see, Planetary Annihilation is as much an arms race as it is a game about machines fighting each other. There are already a few optimised build orders floating about developer Uber’s forums, detailing exactly how you effectively build up a gargantuan force of blood – or should that be oil – hungry bots and vehicles to throw against your unsavoury enemies. The goal isn’t simply to build the largest army, but rather to have the largest, most powerful army. For that, you need advanced units that get churned out by, you’ve guessed it, advanced factories – buildings that can only be constructed by fabrication units that were constructed in the appropriate factory.

When you’ve finally got a vast horde of units, it’s time to go and blow stuff up. Especially since, by this time, it’s very likely that the opposition are planning the exact same thing, if they haven’t started already. What makes an assault interesting is that it turns out that machines are almost as squishy as humans. They’ll pop like a bug in a fire when struck by a bomb or a laser blast, and a titanic force can rapidly be decimated by some fairly meagre defences.

Since victory is a matter of destroying the heavily armoured enemy commander(s), there’s little reason to make a frontal assault, turning every building and defensive structure into dust and debris. Instead, scouting and positioning are key. You send in a scout – probably an airborne one, as they are exceedingly nippy – for a spot of reconnaissance, looking for gaps, collecting intel on the makeup of the enemy force, and, if you have time, shouting out a quick “screw you” as you rapidly zip away, hopefully avoiding enemy AA fire.

Attack orders can be set, units can be ordered to repair, collect materials to turn them into resources, patrol areas, and the way to move towards a spot can even be defined: do you want them to roam around it? Or manoeuvre, marching erratically to the chosen location? Unfortunately, pathfinding is very temperamental at the moment. Units get stuck, trapped and a bit lost frequently, and it’s an appalling pain in the arse having them navigate any part of the environment that isn’t wide and open.

With only a few buildings to worry about until the late game, resources being generated automatically by metal extractors and energy plants, and a command unit at the core of the military machine rather than an HQ, there’s a lot less of the faffing around, gathering resources and turtling that you might see in the likes of Starcraft. Buildings don’t get upgraded, units don’t rank up, so you’re not waiting for extended periods of time, watching your resources increase so you can splash out on a better version of yet another building instead of actually engaging in conflict.

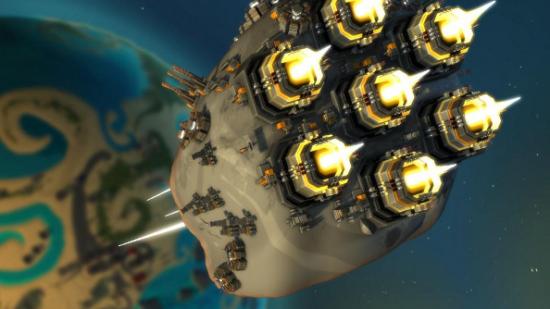

Of course, there are projects that cost a lot of resources to construct, especially once you’ve got some advanced fabrication units. These are the game changers: the nukes, the orbital cannons, the gargantuan engines that thrust a celestial body towards a world, annihilating everything on its surface. But while you are building these horrific weapons of mass destruction, the war continues to rage on. Foes might even cotton on to your plans and fashion appropriate defences: orbital fighters that cripple your cannon, anti-nuke guns that snuff out your powerful missile, interplanetary forces that invade the moon you intend to shoot at the planet.

Against human players – of which you can fight up to five, same as the AI – it can be a delight, even at this early stage. The relative simplicity offered by the small number of unit types and the single objective gives Planetary Annihilation a laser focus, and the breakneck speed and pace lends a constant sense of intensity and excitement to the proceedings.

Beta has added greater depth and complexity with more worlds to conquer and strategies to employ, and while this has slightly hampered the pace, the addition of late game options and more challenging battles is a welcome one. It’s a lot more reactionary now, which is great, because it makes keeping abreast of your opponents’ plots much more important, inspiring you to actually think like a commander. You can’t just focus on what you’re doing, you’ve got to know if your horrible foe is about to bugger off into space or if they are in the process of developing a weapon that can take out your buildings in one shot.

Playing against the AI is a very different experience, but not a good one. There doesn’t seem to be a middle ground where the computer controlled forces are concerned – they are either incredibly aggressive, assaulting you or another AI player within a matter of minute, never relenting, or they are simply broken and utterly passive.

I can’t count the amount of times I’ve seen AI opponents just sit in their base, churning out exactly the same unit over and over again, but doing nothing with them. The first time I decided to experiment with going off-world and sending a moon crashing onto the planet’s surface, the AI did nothing to stop me. In fact, they barely even rebuilt their bases after I nuked some of them beforehand. So I was just postponing the inevitable while I explored new features.

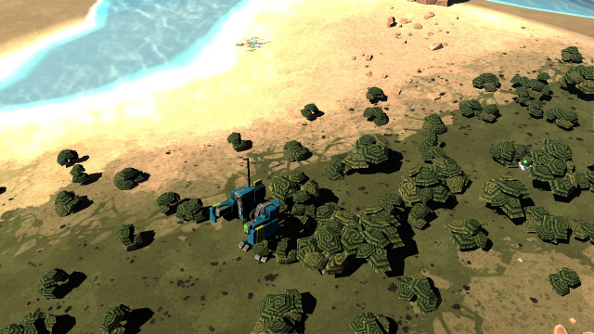

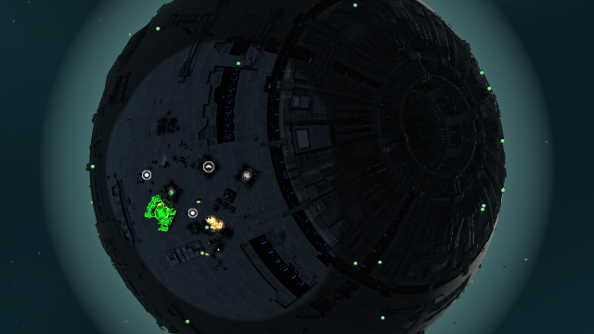

Interplanetary battlefields can be made up of all manner of worlds and moons with a variety of themes like tropical, lava, metal (essentially a Death Star), moon and Earth-like globes, and they all come with their own quirks, from the lack of ocean spaces in some of them, to the abundance of the ever necessary metal used to construct units on others. They are also cute. Yes, that’s an odd thing to call a planet, but I challenge you not to want to just hug them (maybe not the lava world, though, as it’s a tad hot). They look like children’s toys or brightly-coloured foam sculptures.

The toy-like appearance of the planets extends to the units, too, and I’m absolutely certain that I had a wee model mech that looked just like the default commander as a mite. War doesn’t tend to inspire whimsy, but Planetary Annihilation eschews the clinical science-fiction or grey-brown battlefields of so many other RTS titles. It needs to be reiterated: you can have a war on the surface of tiny Death Star.

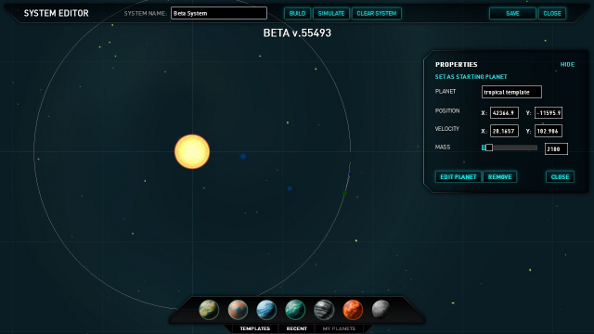

A system editor allows players to fashion their own, unique solar systems by selecting new worlds, dictating their mass, orbit and distance from each other, and then they can be played on. Some of the custom sliders are in the experimental stage, and you can’t change the metal density, but there’s still a wide range of options. Alter the temperature of an Earth-like world, and you’ll see the polar icecaps consume the whole planet. Raise the temperature, and you’ll see that ice vanish.

I like Planetary Annihilation a lot, and I think – if Uber manages to fulfill the game’s potential – a lot of you will too, but it’s just not a great investment yet. There’s a long list of bugs, it can be extremely unstable and it’s not particularly optimised. However, if the only thing holding you back before was the price and lack of genuine planetary annihilation, then now’s the time to jump in. The shift from alpha to beta has been a huge one, and with it has come a drastically lower price. Where before it was almost £60, it’s now just £39.99, though that still makes it the most expensive Early Access title on Steam.

In its beta state, Planetary Annihilation is a finally getting some meat on what was once an, admittedly lovely, skeleton. But to enjoy Planetary Annihilation – and have no doubts about it, there’s a lot to enjoy here – you’ll be paying more than you would be for most finished PC games. Hold off for the time being and you’ll get a cheaper, more polished version when it launches.