To hear Microsoft tell it, DirectX 12 is going to be a breakthrough technology when it comes out as a part of Windows 10. Microsoft has promised, and some early benchmarking has shown, that DirectX 12 can deliver performance gains in the neighborhood of 50% on DX12-capable hardware.

But it’s one thing for the people in the business of marketing the new Windows to paint an idyllic picture of the DirectX 12 landscape. The question is whether those promises will hold up in reality. To answer that, we talked to several game developers, graphics engineers, and computer scientists about what they really think of DirectX 12, and what they think will happen when it’s released into the broader PC gaming ecosystem.

The prospects for DirectX 12 turn out to be fairly complicated. While everyone seems universally agreed that it will provide some gains, it’s unlikely that those improvements will be instantaneous or dramatic. At least, not for those of us playing along at home.

There are a lot of factors that push against and huge, revelatory changes in PC graphics technology that will provide immediate, tangible results to the PC gamer.

Prof. Morgan McGuire of Williams College, an industry consultant and coauthor of “Computer Graphics: Principles & Practice”, explained that, “We’ll quickly see a few small improvements to a small number of games, but DX12 won’t instantly make everything better — it is a developer technology, not a consumer one. Over the next two years we’ll see the real impact as new PC-exclusive games designed for DX12 ship.”

That’s another important point about DirectX 12: the benefits it confers, it confers on developers. And the nature of game development, as Gaslamp Games’ programmer Nicholas Vining pointed out, is “as soon as you get a game running at 60 FPS, your designers and artists will immediately knock it back down to 30 FPS.”

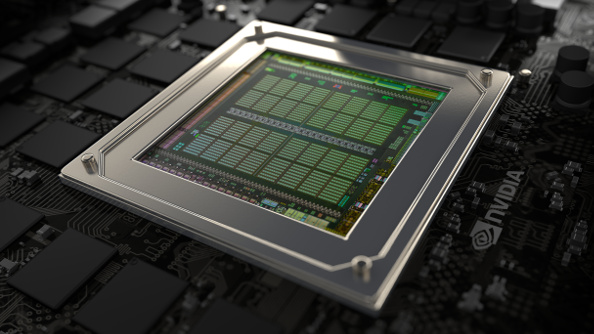

However, most developers agree there are real gains to be made with DirectX 12. That’s because, in many ways, the new DirectX breaks with Microsoft precedent and interacts with the computer’s hardware in new and potentially powerful ways.

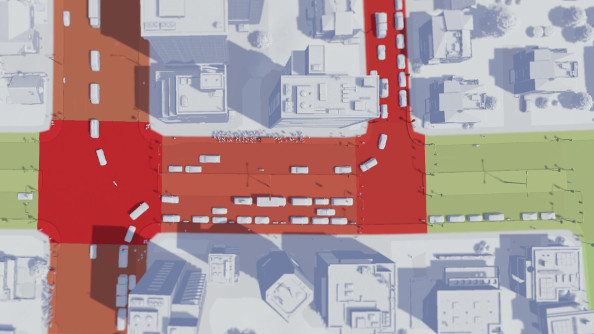

Traffic Problems

“GPUs have been artificially slowed down for years by the CPU and operating system,” said McGuire. “The two processors run completely independently. Whenever the CPU and the GPU communicate, they have to synchronize. …That process takes a little while and requires one of them to slow down temporarily. So, every time that the CPU tells the GPU to draw something, you slow down the GPU while it gets its instructions.”

You could almost think of the way graphics worked under previous generations of DirectX as being a four-way intersection controlled by a single traffic cop. The traffic is carrying all kinds of data. Data from system memory needs to get to the CPU’s onboard cache. The graphics card needs instructions from the CPU. The graphics card is also processing a lot of data itself that it will render and send along to your eyeballs. And, of course, the CPU is also managing an entire game that is changing, on-the-fly, what needs to be displayed, which means what it needs to pull from data and send to the graphics card is changing as well.

To top it all off, all the traffic is flowing at different speeds and, in the Windows ecosystem, you don’t know exactly that path it’s taking to get there because there are tons of different hardware configurations out there.

DirectX was the traffic cop, and all a graphics engineer had to do was fill those lanes with data traffic, set them loose, and the cop would see them all safely through the intersection.

While it’s easy to make this process work, bottlenecks occur constantly as traffic is forced to wait for the intersection to clear. All these inefficiencies add up and cost performance. Most of it came at the expense of the GPU, which was throttled by the delays incurred by the other hardware. For a long time, that was an acceptable trade-off, because it was both easy to implement and because the speeds of the various components didn’t vary so wildly. That’s no longer the case: the GPU is constantly waiting on the CPU, which is in turn waiting on memory, and the amount of performance sacrificed has increased.

This, by the way, is why consoles are able to keep up with PCs despite the often massive gap in hardware capabilities. The closed hardware environment allowed programmers to get write code that speaks directly to the hardware, without DirectX’s managerial overhead.

“Consoles can have a thinner APIs [application-program interfaces] because they are not as ‘multipurpose’ as PCs,” explained one graphics programmer. “…On console you know what that hardware, is so some API calls can be very specific. …You know one hundred percent, down to each single chip, what to expect, and that is a huge advantage when designing an api.”

With DirectX 12, however, some of those efficiencies are coming to Windows. But at the cost of greater complexity on the development side.

Speaking GPU

“DX12 and the next OpenGL API allow the CPU to communicate with the GPU in something much closer to its native language,” said McGuire. “They are actually SIMPLER than DX11, removing big concepts to let the game developer more directly access the underlying GPU hardware. Picture a stripped-down race car in DX12 vs. the DX11 luxury sports car. “

That allows for much greater efficiency, but it costs programmers the traffic cop that many of them have come to rely on. They no longer have an intersection promoting constant gridlock, but now they have to guide all their data through a rather confusing, high-speed roundabout.

“Instead of going through hoops and loops to do something, you have direct access to it, which is more dangerous,” explained the graphics programmer. “Because if you go through a layer [like old versions of DirectX] that checks data for you, you can make an error and something tells you. …If you have direct access to the data (generally speaking), now you are responsible for it, and if you make a mistake you have data problems. [When you] deal with code that is lower level, it’s more delicate and allows you to cause a disaster.”

“There’s no such thing as a free lunch,” said another engineer. “DX11 didn’t have a lot of overhead because its authors were dumb, it had a lot of overhead because it handled a LOT of details that are now the game programmer’s responsibility in DX12. In DX12, you have to manage your own memory, do your own CPU-GPU synchronization, and in general there are many more ways to shoot yourself in the foot.

That’s a shift that will take some time. This is one area where major, multiplatform developers probably enjoy a major advantage: they’ve been writing code that works like this for years, because consoles worked so differently from earlier versions of DirectX. That’s one reason why Microsoft can make this shift now: between years of console development in the game industry, and the arrival of DirectX alternatives like AMD’s Mantle (which also employs low-level, console-like APIs), this is no longer as radical a shift for developer as it would have been in the past.

However, the major roadblock for DirectX 12 is likely to be the PC gaming landscape itself.

Defragmentation needed

Let’s be clear: DirectX could do everything it says on the box, deliver massive performance increases across the board… and it would still have its work cut out for it. That’s because the PC market is, as always, deeply fragmented across many different types of hardware and operating systems.

“You will only shift resources proportional to the market size for DX12 support,” said one developer. “So let’s say half your potential customers are on DX11 still — since you have to run well on DX11 anyway, you’re probably not going to take advantage of everything DX12 has to offer.”

He is quick to point out that those limitations won’t mean DX12 has no benefit, But rather, those benefits won’t quite be commensurate with what is possible under DirectX. The things that are easy to scale-up for DirectX 12 (think draw distances) will be scaled-up. But a lot of other things will still be limited by what’s possible in DX 11.

But with Windows 10, Microsoft appear to be doing something very smart: they’re offering free upgrades to Windows 10 for the first year that the operating system is out. That could go a long way to bringing the critical-mass of users onboard that DirectX 12 will need. But even if Windows 10 proves to a be big hit, it won’t necessarily solve the problem, warns Gaslamp’s Vining.

“Most recently, fragmentation has been in two places: DirectX version (9 versus 10 versus 11) and ‘what does your video card actually support anyhow?’ …A lot of the fragmentation is currently hidden from the user, [but] not from the developer, who has to go through great pains to ensure a good experience, out of the box, on a range of hardware that is between five and seven years old, with drivers that are usually broken.”

If, however, the gains are there to be had, several sources indicated that DirectX might motivate developers to adopt licensed engines. Because while the added programming workload for DirectX 12 might swamp smaller developers, who are often concerned with just getting a game to work in addition to optimizing an engine, engine licensors can put in the labor to optimize for DX 12 alongside many of the other competing standards.

So in the end, while DirectX 12 will probably bring some gains when it’s released as a part of Windows 10, the PC landscape itself is too fragmented, and there’s too much inertia with regard to current practices, to cause a swift change overnight. The most important thing that DirectX 12 signifies, then, might be the ongoing shift to leaner, lower-level APIs that more closely resemble the console’s graphics environment. With Mantle and DirectX pushing graphics programming in the same direction, the graphics processors is on track to become more efficient via these more challenging, but more efficient APIs.

“Ironically,” said one engineer, “I think this may somewhat increase the gap between what PC games are capable of vs console.”