A few months before he made himself the John Lewis of Second Life, a teenage Andre Pires was watching TV in his native Portugal. The broadcasters were, like many business and tech journalists in August 2007, incredulously reporting the sale of a patch of virtual space from one landowner to another for a huge amount of money.

“The world is going crazy,” he thought.

It wasn’t until Christmas came with a new computer from his parents that he was able to discover just how crazy. Pires was familiar with games, but the creators of Second Life insisted it was no game at all. With no objective and no deadlines, set loose in an active market of dedicated roleplayers, Pires anchored himself by scanning the MMO’s classifieds for a job he already knew how to do.

Looking for a second job? These are the best MMOs on PC.

“I’m a real-life bartender,” he told Kelly, a virtual coffee shop owner. “I really know how to treat people and make sure the environment is cool and take care of them.”

Pires was hired, and from behind the till, he was poised to observe the behaviour of this alien world. He watched his customers emoting – expressing actions through text commands, describing their environments “in a way that is actually like reading a book”.

“The better you type, the more accurately you know of the person you’re talking to,” he realised. “And the more both parties take out of the situation.”

Second Life, he understood, was about relationships. And after his first day of eavesdropping, he was ready to learn about the birds and the bees.

“Listen,” he asked Kelly. “Do people get together? Do they have children? What is a sex bed? How does it work?”

Kelly explained that users did indeed get together – but that no children, or indeed NPCs of any kind, appeared in Second Life. She explained that everything Pires saw was built by residents. And she explained that a bed alone was simply a 3D object in the world – only scripts attached to that object could force a player avatar’s mesh to animate and turn it into a sex bed.

This last fact turned out to be very important to a significant proportion of Second Life users, as well as in Pires’ future career.

Within three days, Pires was the coffee shop’s manager. Unfortunately, there wasn’t much to manage. Virtual patrons don’t buy espressos or paninis, it transpires, and so the shop was getting by on tips – in-game currency placed into a jar as a show of support.

It wasn’t enough. Second Life developers Linden Lab make their money by selling regions – sims – to users, and those users sublet those regions in chunks as ‘parcels’. Kelly was a tenant, and her coffee shop wasn’t nearly successful enough to make rent.

Pires took it upon himself to drum up business – travelling to other sims to persuade users into the shop.

“Come and visit,” he pleaded. “I will give you a drink.”

After a week, the place was packed. And a week after that, Pires was bored.

“I’ve always been active in my professional life,” he explains. “I wanted to do something bigger, and started to understand that people can build there.”

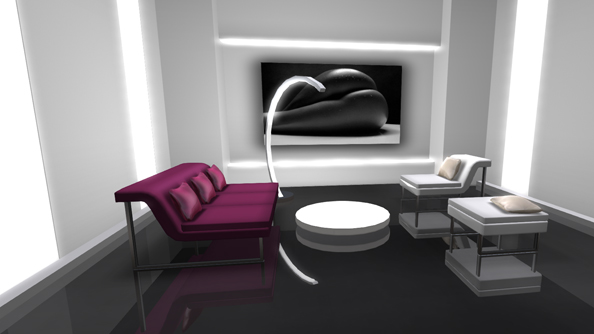

Playing with Second Life’s tools for mesh construction and importing textures, Pires began to reverse engineer the items he saw other users making. Buoyed by initial success and with Kelly’s blessing, he rented his own spot within an art gallery and began selling sets of furniture.

Where the coffee shop’s lack of physicality had been a problem, here it was a boon. Once Pires had designed and sold one piece of furniture – a bed, jacuzzi or chaise longue – there were no material costs involved in selling it again, and again, and again. He could afford to hire a sales team on a generous commission – 50% – to go forth and find customers, knowing that happy buyers and their friends would right-click on the item, see Pires’ name, and come back to him directly for subsequent purchases.

Within a month, Pires had a “bunch” of people working for him. Within three, his small shop had grown to cover a full quarter of a sim. And it took him precisely one year to reach maximum shop size and make $3,000 in savings.

“After that, every week I started doing $3,000, because it was snowballing,” Pires remembers. “I was doing more products and more employees and everyone was enjoying it because they didn’t have to build shit.”

By now, Pires had a huge customer base. But real-life hadn’t caught up: he was still a bar manager, making less than his Second Life avatar.

“I can’t do this anymore,” he told his boss. “I’m in this job but I could be in Second Life, evolving my stuff, and I would make triple the money you would give me.”

With Europe in financial crisis, Portugal in danger of going bankrupt, and all of Pires’ income in dollars, he decided to up sticks to Mexico.

“It’s near the Caribbean, it’s summer all year round, [and] things are cheaper,” he reasoned.

The virtual furniture magnate, who had no 3D modelling experience prior to Second Life, is now self-funding survival game Genesis from his “two floor house with a pool”.

“I’m not trying to brag,” he protests. “I was a simple bartender and I had a poor car and lived with my parents. I stopped playing FIFA and CoD and all that crap that wouldn’t take anyone anywhere, and [my friends] all criticised me. I kept telling them: ‘One day this thing is going to get me a lot of money’. And I swear to God, my girlfriend reminds me of that every day. She quit her job. It changed her life and it changed my life.”

In November 2006, Businessweek devoted their cover to the avatar of Second Life’s first millionaire: Anshe Chung (“I relate this all with a straight face,” wrote its correspondent, “but I still find it rather hard to believe.”). In the gold rush that followed, however, very few found their footing like Pires did.

“You need perseverance,” he believes. “I was there 12 to 16 hours a day, looking at every detail, trying to understand what to do to make it better. It needed a lot of work. A lot of people fail and give up.”

Pires attributes his success to at least one old-fashioned business principle, however: sex sells.

“They go to your store as a couple and they want the bed. Why? Because they want to get laid,” he explains. “At that moment they’re excited, they’re horny, you hear the money drop, and they go out. Some are different – they look at all the animations and they send you a notecard: ‘I like this model, I want it in pink or red’. But most sales happen in a flash.”

Linden Lab used to offer two main grids: one for adults only, and another for teens. But in 2010, they closed the teen grid due to operating costs. Is Second Life’s reputation for sex deserved?

“Second Life is like the internet,” offers Pires. “If you go into that world there are endless opportunities. In Second Life, it’s easier to do sex than to study engineering, show your car or run a company. People are driven by erections.”

Thankfully, for those keen not to believe that erections are the secret behind the boom of a virtual department store, there’s an alternative explanation.

“Second Life is full of people who are frustrated with life,” says Pires. “There are a lot of old people, people that lost their wives. They just want a friend there, to have company. If you are a shy person or you have problems, it’s very easy to hide behind an avatar and talk and let go, be gentle or brave. Even though you’re clumsy in real life in there you can be a star – buy an animation and you can dance really well, buy cool hair and you’re not bald. That’s why it was so fast to explode in there. At the end of the day, relationships are the main thing.”