Are you among the million or so Steam users who bought a copy of Space Engineers at some point in its development? Well, congratulations: not only did you acquire a lovely game about trying to build space objects faster than space can dismantle them, but you also helped fund fledgling efforts to create a childlike AI capable of taking us far beyond the limits of human understanding.

Bargain.

Five minutes into my call with Marek Rosa, the Keen Software House founder wants to emphasise something: he didn’t assemble a team to build a wildly successful sandbox game simply as a mercenary means of funding an artificial brain. Rosa has always wanted to make games, and they remain hugely important to Keen: witness Medieval Engineers, their siege-flavoured sequel. But AI has long been part of the plan.

Rosa read sci-fi books as a child – and at the age of 14 saw a documentary film about robots at MIT.

“Of course, it was very simple – but in that moment I realised that robots and AI, if done properly, can solve everything else,” he said. “We don’t need to invent all these medicines and space travel, because the AI will be designed to think faster and better than we as humans can.”

Rosa considered starting up a dedicated AI company 10 years ago – but couldn’t see a way to fund his efforts in the short-term without bowing to investors. Instead, he set up Keen Software House with a dual purpose: to make games first, and research and develop artificial intelligence second – both independently.

The plan paid off when Space Engineers captured the imagination of players in Steam Early Access with its hard sci-fi approach to creation.

“I realised, okay, I have more money than I surely need for myself or for the game team,” said Rosa. “Let’s just use it for AI.”

Rosa has hired on an entirely separate team of 15 computer scientists and engineers, and stuck a $10 million research fund behind them. The AI work itself isn’t spectacularly expensive – but having that cash reserve allows Keen Software House to look far into the future.

Rosa believes in the capacity of AI to help people. The idea is to build a computer with the cognitive ability of a smart human being – and ask it to optimise its own hardware and software. And then once it’s done self-improving, ask the same again – until its intelligence has grown exponentially.

“Let’s use it for self-driving cars. Let’s use it for writing better software. Let’s use it for making games,” said Rosa. “But later, I’m assuming that it can be used as a scientist.”

Rosa foresees AI crunching data on a scale beyond human comprehension – finding patterns and causality in the information we already have. Then, perhaps, it can conceive and test medical hypotheses, assist entrepreneurs, or further space exploration.

Keen reckon they’re least a decade away from human-level intelligence – but have built a tool for designing the architecture of artificial brains, and an AI capable of learning to play Pong.

Most recently, the team have plonked their AI in a top-down virtual maze where, with no prior knowledge, it gradually learned to flick switches to unlock doors, better optimising its route to ‘treasure’ with each repetition.

But they haven’t endowed their AI brain with the most advanced intelligence they could muster – rather allowing it to begin in a “child-like” state, with just a few innate reflexes.

“When our AI is born it has no knowledge about itself, its body and its environment,” said Rosa. “And it builds this knowledge by interacting with the environment.”

The brain is designed to be self-optimising: learning efficiency through trial and error in the same way we achieve mastery over games. Keen plan to expedite that process by acting as ‘mentor’ figures – plugging into the AI to teach it new behaviours.

I note that mentoring sounds a lot like parenting.

“In my opinion, it’s the same thing,” agreed Rosa.

Does he feel like a proud parent?

“Not right now, because the AI is not really that smart,” he laughed. “But after it becomes more advanced and able to understand more complex situations, then I think I will feel like a parent.”

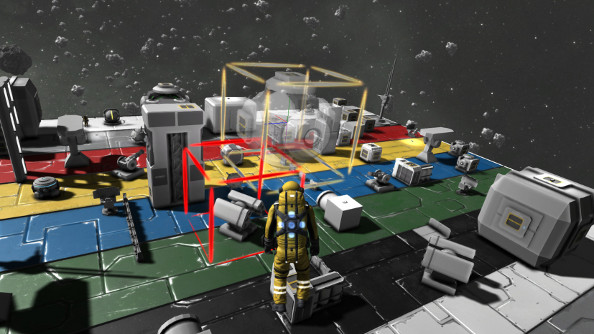

Keen’s AI isn’t designed specifically for games – but it’s certainly compatible with them. They’ve already proved that internally, by connecting their ‘brain simulator’ tool up to Space Engineers – spawning a six-legged robot in a labyrinth. Via a camera on its head, the robot was able to navigate the maze.

And in two months’ time, Keen will release a free modular brain simulator that will allow Space and Medieval Engineers players to design and teach their own AI. Medieval Engineers’ peasants should prove to be particularly satisfying test subjects.

“The player will be giving a peasant reward or punishment in certain situations,” explained Rosa. “And the peasant will learn where he is getting the reward, and try to get to that situation again.”

The AI brain can learn, too, from the traditional game AI in Medieval Engineers.

“It probably won’t be that easy at that beginning, because the [AI brain] will not have structured understanding of the environment,” said Rosa. “But after some time, we can plug this behavioural tree AI out and the brain simulator AI should be able to continue to emulate what it has learned from the standard AI.”

X-Com creator Julian Gollop last year bemoaned that AI had become a neglected area of game design – one that didn’t nearly take full advantage of the processing power of modern PCs. Rosa agrees, although he points out that it’s sometimes not worth developers’ time to build complex AI that players are unlikely to notice – or else AI is designed to be just stupid enough to be beaten.

But the surprise hits of last year were Alien: Isolation and Shadow of Mordor – two games which made AI their centrepiece features. Rosa thinks there’s increasing potential for AI to be the key sell for games of the future.

“What it could add to the games industry is AI that is really adaptive and that can learn new things just by playing the game with you,” said Rosa. “It will not be so predictable.”

There’s still the killer question, though. Or rather, the Terminator question. What kind of safeguards do you put in place for an exponentially self-improving AI?

“At this moment we shouldn’t be worried – an AI playing Pong is unlikely to be able to take over the world,” began Rosa. “But it’s a good time to start thinking about these things.”

He recommends the Machine Intelligence Research Institute’s studies into the perils of AI – and points out that Keen’s AI gains its moral code from human teachers.

“We will try to train this AI to have the same values as humans,” said Rosa. “If this child AI steals, it will get a bad signal from its teacher and will try to avoid getting to that situation again. We need an AI that is on the same social and emotional level as humans.”

Clever robots for Space Engineers, then, and an assurance that they probably won’t learn to kill us all. Bargain.