Three years is a long time in gaming. When Steam’s Early Access program launched in 2013 it helped bring games like Kerbal Space Program, Ark: Survival Evolved, Prison Architect and DayZ to light. For better or for worse it’s changed the landscape of game development, and in those three years it’s changed a lot itself. Abandoned release schedules, ruinous updates and absentee developers have had a lasting impact on how customers perceive Early Access, which in turn affects the devs who still believe that it’s the best place to make their games.

After games from small teams with unique styles? Check out the best indie games on PC.

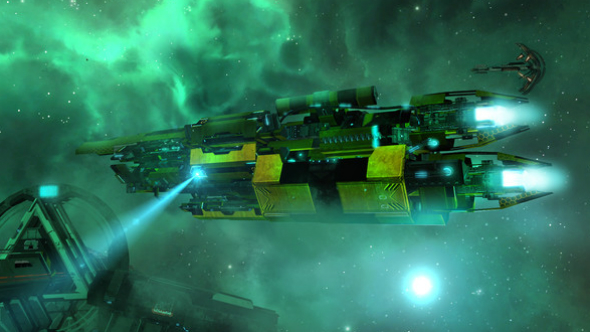

Starpoint Gemini 2 was one of the first games to enter Early Access after being scouted by Valve as a good candidate for the program. “I think we were the fifth or sixth game ever to get into Early Access,” explains Little Green Men Games CEO Mario Mihokovic. “We weren’t some great visionaries that knew how this was going to play out. Basically, we were developing the game – we’d never heard about Early Access because it didn’t exist – and one day some people from Steam came to see it and said they were preparing a new program. They will be releasing unfinished games, and since we were talking to our community quite a lot, we would be a very good addition.”

At that point Steam were only accepting games in the very early stages of development, rather than the beta stage games that routinely enter the marketplace now. “The scheme insisted on the game being as unfinished as possible. It was their number one priority, they said, ‘if the game is in beta, or even close to beta, forget it’. The game needs to be as unfinished as possible so that people actually have enough time to be included in what they’re investing in.” For Starpoint Gemini 2 that meant basic controls for moving a ship around in space and nothing else – the collision box didn’t work, most keys didn’t work, firing didn’t work and combat didn’t work.

Although players buying into the Early Access build of Starpoint Gemini 2 had almost nothing to play, most weren’t phased by the premise. “The community craved some form of space game then, and then they also realised they could actually be involved in its development. It enrolled pretty slowly at the beginning, but after three or four weeks of intense discussion with the community – we actually spent half of every day typing with the community in Steam forums – these same players started noticing that what they were talking about was appearing in the game. They had an actual impact, so they liked it very much. It’s changed since then.”

Little Green Men Games are adopting the same development approach for their next game, Starpoint Gemini Warlords, which is currently in Early Access, but the problems they face are different this time around. “The problem is people have different expectations right now,” says Mihokovic. “There were a number of very successful games – I’m not including our game in that: we were quite successful, but not on a triple-A level. When several games made excellent, excellent sales numbers due to Early Access, it became a very interesting program for big developers, so they also started making games there.”

However, some of the bigger studios weren’t willing to listen to the creative input of their audience. “In many cases they actually did not care about any community ideas, their desire was to simply use Early Access as a means to double their release chances. That’s completely legitimate, Steam has nothing against that. Also at that time, Steam started to accept games that were in advanced beta and even almost completely finished, they just lacked some polish. In our case it actually created an entirely different expectation from players,” explains Mihokovic. Over the course of two years, expectations of Early Access had changed to the point where most customers were expecting a beta-stage product – they could accept some bugs and inconsistencies, but skeletal games had ceased to be the norm.

This leaves Starpoint Gemini Warlords and its developers in an unenviable position: still wanting to include their audience in the development of their game but facing increased pressure from customers who expect more for their money.

“Now, many more players actually expect, ‘Sure, it’s not a finished game, but I think unfinished means it’s finished and it just has a few bugs.’ They are two very different things,” explains Mihokovic.

While negative reviews for Starpoint Gemini Warlords are still relatively few and far between, the sheer commonality of complaints about the general state of the game is evidence of how much perceptions of Early Access have shifted. “90% of the negative reviews are – ‘Where is the content?’, ‘This game has a lot of strange bugs’, ‘Stay away from this game, I got a desktop crash twice in 30 minutes.’ -You get the idea,” adds Igor Dudjak, content manager for Little Green Men Games.

Mihokovic doesn’t blame Steam or its customers. “Development times and due dates in early access need to be shorter next time. People don’t have a lot of patience anymore due to a lot of previous failures in Early Access, and they don’t want to wait three years for the game to exist. Maybe it was our mistake, maybe we should waited for a more complete version. But then again, we really enjoyed talking to people and getting their ideas. Sometimes people have wild ideas that are actually not too hard to implement and really improve the game.”

For all of Mihokovic’s ruminating, Starpoint Gemini Warlords is performing almost as well as their first Early Access outing, which is well above the average for Early Access titles now. “We got a fresh set of data from Steam about how Early Access goes these days. We were actually quite shocked because the average sales numbers and success of Early Access games now in Steam is about 60% lower than it was when we did Starpoint Gemini 2 – it’s a lot worse.”

One of the biggest faults of developers who launch alpha-stage products on Early Access is that they promise too much. Some developers fear that because their game is missing so many features, they’re better off launching it with mocked-up screenshots of what they hope it will look like. But Mihokovic is keen to point out that you can’t get away with anything in Early Access. “Don’t lie to your audience, because in Early Access the game is small and a lot of things are missing, so every player will go through all of the content very fast. You can’t lie to them, they’re going to see it all in 20 minutes.”

Structure is also key. “You need to write down a plan,” explains Mihokovic, “of how often you’re going to update the game and what you’re going to place in each update – people want that plan. Today it’s more dangerous, because of all those failures in Early Access, people are very sensitive. If you release the game in Early Access and don’t follow it with any plan, they immediately place you in the category of game developers that don’t care.”

Mihokovic believes the blame for the platform’s increasing disrepute rests solely on the shoulders of those that Early Access stands to benefit the most: developers like Little Green Men Games. “It needs to be taken seriously. You can’t launch the game in Early Access, forget about it, and just talk to people when you’re ready to release it. For me that’s not Early Access, and many developers have handled it in a wrong way. No-one was too agitated after two games went to Early Access in a wrong way. After five games, it was becoming visible. But after 50 games people are now very aggravated, and they have a prejudice against Early Access, so that’s something we need to deal with now.”

It’s an admirable stance to take, but when all Steam ask of budding Early Access developers are the system requirements, a store page and temporary assets it’s easy to see how failures continue to happen in such large numbers. Ultimately, only the developers can be blamed for overextending themselves or failing to keep their audience up to date, but managing the bloat of Early Access developers on Steam still appears to be nobody’s responsibility but theirs.