You’ve probably heard of Steam Spy. The aggregator is a tool for everything from market research to constructing opening broadsides in internet fanboy arguments. It uses Steam’s publically available player data to estimate owner numbers, and thus is used to figure out how many copies a game may have sold.

While you’re here, check out the best PC games there are.

It’s constantly referenced by players, journalists, publishers and developers for a variety of reasons – but how accurate is it versus Steam’s unpublished numbers? What do developers think of it, and the ways it’s used? Importantly, do they wish they could be removed from it?

How accurate is Steam Spy?

Across the dozens of devs and publishers we spoke to, the general consensus was: ‘good enough’. It’s not exact, as Steam Spy itself admits on every game page, giving a ± figure. Around 10% seemed normal, as mentioned by Alexis Kennedy (former Failbetter, Sunless Sea):

“Back when I ran Failbetter, Steam Spy was within 10% of our figures whenever I checked. I don’t have more recent data than June 2016, though. Broadly speaking, I think of it as approximately as accurate as the kind of friend-of-a-friend info you get at conferences – ‘x told me they’d sold about 50K copies’.”

Ben Cousins (The Outsiders, Project Wight) also stated “they are usually accurate within 10%.” Where inaccuracies were noted, developers said that Steam Spy’s figure was slightly lower than their tracking.

Cliff Harris (Positech Games, Democracy 3) saw it even more right:

“Steam Spy estimates for Democracy 3 are about 5% out in terms of pure owners of the title, which is extremely accurate, although in terms of working out how much money a game made, that’s a fairly useless statistic!”

While Kristina Halvorsen (Krillbite Studio, Among The Sleep) provided exact figures:

“For us, Steam Spy is pretty accurate. Steam Spy says 186,598 ± 13,183, and we have 186,104 sales on Steam. I have seen others that have pretty accurate numbers as well.”

As did Ivan Slovtsov (Ice Pick Lodge, Pathologic):

“On all our games Steam Spy shows accurate numbers with real number always within the stated margin of error. For example, at this point Knock-Knock sold 94,000 units on Steam, with Steam Spy showing 96,863 ± 10,577.”

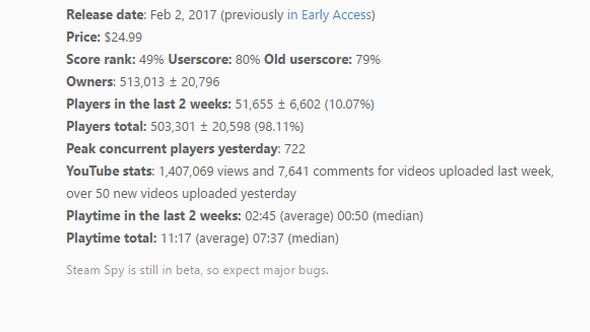

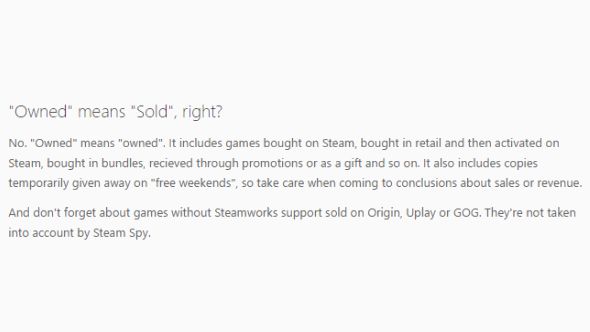

Of note is that free weekends mess with these numbers, as is also called out by Steam Spy on games where that has happened, drastically increasing the owner numbers. Free-to-play games’ owner figures are similarly useless, since it will just be a track of active Steam users who’ve had it added to their library. Martin Frain (Edge Case Games, Fractured Space) says active player numbers “are generally pretty close to our own tracking, but their Twitch and YouTube numbers are less accurate.”

The numbers also become rather pointless if the sales of a title have been in the low thousands – take Beeswing for example, from Jack King-Spooner:

“It’s one hundred percent accurate, stating owners [at] 2,458 ± 2,780. The correct number of owners of Beeswing on Steam is 976 so Steam Spy nailed it. But when the numbers get bigger, that margin of error means a lot less. Being a few thousand out on a game that sold squillions is very indicative.”

Daniel Ratcliffe (Redirection) had a similar experience:

“I wish Redirection had sold as well as Steam Spy says it has! Instead, it overestimates my numbers by about 150%. I suspect this degree of inaccuracy is common for many smaller indie games.”

Mike Hergaarden (M2H, Verdun) gives his estimate on the accuracy line:

“[Steam Spy is] very accurate, as long as you sell over at least 10,000 units. In our experience, the accuracy increases for bigger volumes as long as you haven’t done a free weekend or such.”

Sergey Galyonkin, who operates Steam Spy, gave us his exact figures:

“Steam Spy uses estimates with 98% confidence interval. It means that 2% of games will be [outside] the displayed interval even with the margin of error. It’s also completely inaccurate for small games. Everything under 30K should be discounted as completely inaccurate – the sample size is just not big enough.”

Andrew Smith (Spilt Milk Studio, Lazarus) was an outlier, saying there were issues at both ends.

“We find them pretty inaccurate. At the more extreme ends of the spectrums (very high sales, and very low) the more inaccurate the system seems. This is from our own experience as well as having talked to plenty of other devs about it. The main area of disconnect and inaccuracy lies in sales and discounts, and those are naturally more egregious when it comes to successful games… and it seems most people only look at the successes rather than the overall picture.”

Dan Pearce (Four Circle Interactive, 10 Second Ninja X) would like to see these inaccuracies more directly highlighted:

“I have a few issues with how Steam Spy represents its data. If you go to the site’s About page, it does state that it estimates and doesn’t provide ‘100% correct’ information. I know a few developers who have been misrepresented through the site’s estimates and can understand how this would hurt them. Obviously Steam Spy isn’t solely to blame for that, people should check where they get their data, but I do find the decision to not immediately clarify what Steam Spy does pretty shady. Sales data needs context and Steam Spy seems to deliberately tuck that away or ignore it.”

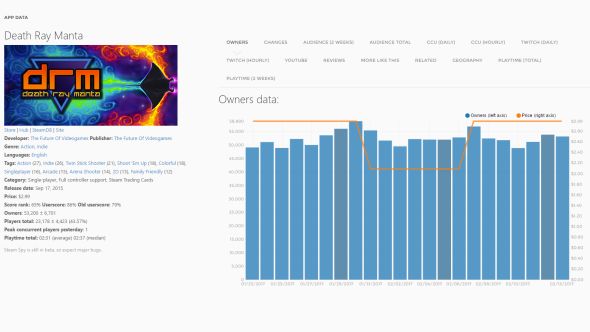

Robert Fearon (The Future of Videogames, Death Ray Manta) thinks that isn’t accurate enough:

“Last time I looked, and admittedly this was a few months back now, they were just within the margin of error. So they’re sort of wrong enough that I wouldn’t feel comfortable with anyone trying to draw any meaningful conclusions from, just not wrong enough to be entirely useless – though sorely in need of some context also.”

Steam Spy can’t tell you how much money a game made

This was the number one complaint from developers in terms of what they see going wrong when Steam Spy is consulted by players, journalists and the like. There are simply too many variables to consider that the service does not track and it can cause issues for developers.

Andy Hodgetts (The Indie Stone, Project Zomboid):

“Really, the only [problem] with things like Steam Spy is when people attempt to draw financial conclusions from the data. If a game’s RRP is $10 and Steam Spy reports 100,000 owners that does not mean the developers have made $1,000,000. In all likelihood [the truth is] far, far, far from that amount when you take into account the slice [of] the pie the publisher and distributor / marketplace take, sale prices, frequency and proportion of sales that represents, other avenues in obtaining Steam Keys such as bundles etc.

“So I don’t particularly like it when people use the data in this way since all it typically yields is the implication that people are more profitable than they are which can lead to unrealistic expectations in terms of the average performance of indie games.”

Martin Wahlund (Fatshark, Warhammer: End Times – Vermintide) explains these aren’t all actually Steam-bought either:

“I think it is important to understand that Steam Spy’s data is based on distributed keys, not sales. So if you use it for measuring the audience it is great. If you want to understand how much the publisher/developer has earned it is almost impossible as you don’t know the average price.”

Alex Nichiporchik (TinyBuild Games, Clustertruck) points out two common obstacles that show why owners does not equal sales:

“Steam Spy’s numbers are pretty accurate outside of giveaways and bundles. For example, if you do a beta and giveaway a ton of keys that then turn into the full game, that’ll get counted on Steam Spy. Using Steam Spy properly in the press is totally fine. As long as you can track down major things like sales, bundles, and giveaways. That becomes the difficult part.”

He also explained how TinyBuild have used Steam Spy in the past:

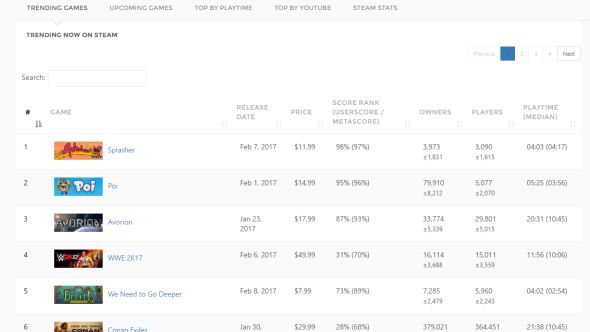

“It’s good to see what genres are taking off, how certain games have steady sales despite not being in the top charts, and gives us as a company a way to foresee trends.”

Andrew Smith believes that the required knowledge for interpreting Steam Spy data means players and journalists should stop using it.

“I wish everyone outside of the dev community would ignore it. There is a ton of specialist knowledge needed – a lot of it gained solely through contacts, experience and time spent in the industry that renders it vaguely useful. I worry that using it as any kind of measure of success perpetuates common misconceptions about the industry, what success is, what is successful, and basically just takes the talk away from what’s interesting and important (the art and craft of games) to what isn’t, but seems to get everyone sounding off (what game is ‘winning’, what game is ‘losing’).”

Matt Raithel (Graphite Studio, Hive Jump) wants to see the press use it less too:

“I think quoting Steam Spy data isn’t a fair practice as it doesn’t offer any guarantee of accuracy and the service itself is still listed in beta. The best practice to follow (if sales numbers are necessary for an article or survey) is to reach out to the developer or publisher directly to get accountable data.“

Also of note is publishers mentioning that developers can’t simply say ‘these games did well according to Steam Spy when explaining ideas. It’s a valuable source, but not one to be taken in isolation, as Paul Kilduff-Taylor (Mode 7 Games, Tokyo 42) explains:

“I definitely think that people are taking too many specific inferences from the data; game pitches [that] are like ‘x game and y game did great – here’s Steam Spy – therefore my game will do great’ are not ideal. It’s best used as a ‘did this do well or not’ metric rather than anything else – even that can be confusing too, as it presumes you know the dev or publisher’s expectations for that title.”

Trent Oster (Beamdog Interactive, Baldur’s Gate: Siege of Dragonspear) worries that having data on Steam Spy can lead to problems only for studios that can’t afford them:

“If a game is a huge success, everyone knows it, so I think the concern is more around low selling titles and the potential black eye developers can get from a poor performing title. It seems many of the digital distribution options are kind of a popularity contest that is self-reinforcing, so having a low sales number could bias that behaviour even further. [For example, if the] press report low Steam Spy numbers, fans avoid the title [and] assume it isn’t a good game.

“I would suggest enthusiasts look past just the numbers and actually look at the games, because some really great titles launch head to head with really strong competition or fumble the launch and lose out on the initial sale, which handicaps them in the popularity contest.”

Sergey Galyonkin says people are learning:

“It’s getting better over time. I generally feel that both the press and game developers still need to learn a bit more about statistics and polls. But we’ve gone a long way from ‘this game has four million owners, so it must’ve made 4M times $60’ to ‘this figure takes discounts into account and is still an estimate of the market worth and doesn’t represent actual sales.’

“I used to cringe and then go to comments sections of some sites writing about Steam Spy’s data in the first six months or so. I don’t do it anymore because journalists and bloggers improved their knowledge of this subject.”

Should Steam Spy let developers remove their games?

So, let's see what happens if I restore all the removed games at Steam Spy.

— Steam Spy (@Steam_Spy) 25 August 2016

The majority of people we asked said they would not remove their games from Steam Spy, if given the option. Here’s how Gambitious Digital Entertainment (Hard West) sum it up:

“Steam Spy has become a very useful service for the industry. It allows different parties like developers, publishers and investors to quickly check [whether] the information given is actually accurate or not. Before Steam Spy you had to basically just take whatever sales information you were given at face value, at least during the initial conversations. This was especially an issue with publishers, as they used to be able to hide the real sales numbers and incorrectly report them in order to pay out less to developers in royalties. Likewise, a publisher can check a developer that’s asking for a million dollars for their project since their last game made 10 million. It is also helping everyone to get a better picture of the overall health of the industry, and can be very useful for creating realistic(ish) projections for new projects.”

Ivan Slovstsov has similar feelings:

“The ‘downsides’ of this transparency are that it makes it harder for big companies to take advantage of the market based on the exclusive access to information – since they most certainly were doing all these calculations years before Steam Spy – and to misinform partners – like, for example, developers or stakeholders being misinformed by a publisher – about how the game performed. Which, in my opinion, are not downsides at all.”

Ben Cousins said that he’s “perfectly happy with it. To be honest, I wish Steam would just publish numbers,” showing there’s some demand for even more openness.

There are also upsides for other developers, explains Pete Bottomley (White Paper Games, Ether One):

“I think it’s fine for people to know how your game is doing and development transparency is something we’re always open to. It might help similar studios to ourselves budget and forecast their own game production. However, I do believe that just because a game is similar, there are many other contributing factors which may impact game sales so I wouldn’t recommend a developer rely solely on Steam Spy for that, but it is a good starting point.”

Andy Hodgetts sees benefits for customers too:

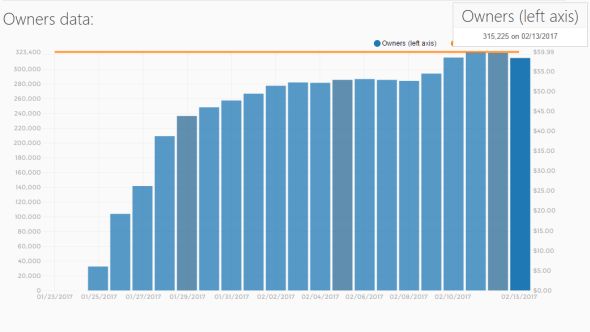

“I see no reason why we would choose to remove our own game from Steam Spy. With an Early Access title, a healthy looking sales graph (regardless of how misleading it is in terms of absolute financial success) may provide potential customers some measure of comfort that the game is unlikely to cease development any time soon.”

James Parker (Ground Shatter, SkyScrappers) finds it useful, and believes it will get more-so in the future:

“I’d never ask for my games to be removed, because I’m unsure what the point of such a move would be. Despite the shortcomings of the service, it’s still useful as long as you’re willing to accept that the numbers you see don’t reflect a true picture of sales. Over time, I think Steam Spy’s algorithms will improve, and I have no problem with the estimations made, but it’s what people do with them that’s often the bigger problem.”

While Julian Gari (AutoAttack Games, Legion TD 2) just likes having it:

“We probably wouldn’t remove ourselves. We’re happy to contribute to the data set, and as a statistician myself, I love having access to the data.”

Robert Fearon would prefer not to be involved though:

“I’m generally not entirely happy with the way the information is presented given how much more information that Spy can’t provide would be needed to make any sensible decisions from [it].

“In the end, the decision was taken from me regardless and it seems like I’ve got better battles to fight than one with a stubborn data hoarding service so that’s sort of where I’m at. To be honest, I probably wouldn’t hesitate to remove my games these days given some of the analysis that’s crept out since I last thought about this.”

Paradox Interactive, thefirst company to ask Steam Spy to remove their figuresbeforethem being reinstated a while later, declined to comment on this article.

Gary Chambers (Introversion, Prison Architect) doesn’t think it’s okay to tell developers they can’t remove their games:

“Personally I’m pretty neutral on the whole thing. It’s an interesting tool, though I could understand why some people wouldn’t want this kind of information released and I think that should be respected. If a developer wants their game removed then it should be removed – from what I understand, some devs have some very legitimate reasons for not wanting these numbers out there.”

Luke Herbert (Wonderstruck, Boundless) points out that the reaction to asking to be removed probably wouldn’t be worth the effort:

“Trying to remove your game from Steam Spy at this stage is risky. Some developers, particularly those developing multiplayer games, have already tried to block some of the data shown on Steam Spy. But when players and the press notice this, the result can be negative if the public feel you are hiding important information about the game they’re currently playing or about to buy. The public has grown a lot more cautious with their purchases after a number of high profile failures in the crowdfunding and early access area.

“It makes you wonder if having this information in the public does more harm than good for the games on Steam, especially when other platforms do not share this information publicly. It’s too early to say if this is the case, but if there was evidence that backed it up, it might be more beneficial to remove all the data from Steam Spy instead of removing individual titles.”

However, there isn’t a publically-available alternative, as Tanya Short (Kitfox Games, Moon Hunters) points out:

“If that’s the data you’re looking for, Steam Spy is the best. You just have to ask yourself whether there are more interesting stories and creations out there beyond sales figures. There are probably game developers among us RIGHT NOW who are analagous to Van Gogh – toiling in obscurity, brilliant, and some institutions are trying to raise them up, but it’s not a conversation most people are interested in having until the game sells a million units.”

Daniel Ratcliffe has similar concerns:

“I don’t mind the press using the figures on Steam Spy to estimate sales figures, but they could probably do a better job of making clear they are estimates, with pretty significant error bounds. A better question to ask though: is the number of copies a game has sold the most interesting thing to say about it? The gaming public could do with being reminded every now and then than financial success of a game is not 100% correlated with its quality.”

Overall, our discussions with developers revealed Steam Spy is a useful tool, for them and us, and the majority would rather it existed than not. The issue comes in how it’s used, by us as journalists and by players as fans. It’s a single datapoint, not the be-all, end-all of any discussion regarding a game’s success.

That’s the devs thoughts, what about you? Let us know in the comments below.