Europa Universalis, but in space. What a pitch. That is, broadly, what Paradox Development Studio have tried to created with Stellaris, kicking their complex brand of strategy into a future filled with alien leviathans, dictators with tentacles, and plenty of exploding space ships. It’s more than just those five words, however.

Fancy playing Stellaris online? Here’s what we thought of Stellaris multiplayer.

It’s a 4X game, for one, which means that straight away Stellaris feels more focused and objective-driven than not just EU, but most of Paradox’s grand strategy fare. But almost all of the Xs have been tweaked in such a way that, though they haven’t been redefined, they are capable of surprising with unexpected consistency.

I want to talk to you about the noble Psaurion species. They are a race of genius space dinosaurs who want nothing more than to spread their scaly limbs throughout the galaxy in the hope of learning more about the universe they inhabit. They are staunch individualists, have long since shrugged off the yoke of religion and embraced a life of materialism and scientific progress, and though their bodies may be weak, they are more than capable of standing up to any alien aggressors thanks to their vast robotic army.

This description of my latest Stellaris species has no fluff. Everything you see written above is both integral to the race and grounded in the mechanics of how they function, as well as the narrative that has organically developed as I’ve led them on their adventure across the stars. And much of this description comes from the race customisation feature that you might find yourself dabbling with before you even look at space.

So their intellect comes from the intelligent trait, one of four negative or positive traits selected from a much larger list that includes decadence, longevity, agrarian proclivities and so on. The fact that they are weak also comes from this list. On the surface these are mostly stat modifiers, but they also inform a lot of later choices.

The Psaurions’ natural physical limitations, for example, means that their ground troops – used when conquering a planet – are a bit rubbish. This is what inspired me to research robotics, giving me robotic soldiers to make up for the squishiness of my organic ones. But this also sent me down the path of exploring robotics and AI in greater detail. While these automatons started as servants and warriors, I eventually gave them the same rights and privileges as my organic citizens, limiting how much control I had over them, but also making me feel much better about all those years of enslavement.

A whole arc of the story of the Psaurions is now dedicated to the liberation of synthetic lifeforms, and it all started because I gave my species the weak trait that simply makes them crap in a fight.

The impact of these very early decisions can be seen even more clearly with the ethics of your government. At species creation, there are two circles that offer up various ideologies. There’s your militant ideology, and it’s opposite, pacifism, collectivism versus individualism, xenophobia and xenophilia, and finally spiritualism and materialism. The second circle is full of fanatical versions of these ideologies, and you pick one from each.

Again, these are just stat modifiers. But that’s not where their effect ends. First off, your selection determines what forms of government you may select, running the gamut from a science directorate where an elite council of boffins rules the roost, to free and open democracies.

So making these wee choices that, at first, appear to just offer tweaks to your species’ stats actually has a dramatic ripple effect, informing the entirety of the game. They determine if you have elections or not, how your citizens react to slavery, how other factions view you, even if you can declare war or not. Look just behind the numbers, and these traits are revealed to be important, meaningful decisions. Apart from Endless Legend, I don’t think there’s another 4X game that really encourages players to understand exactly who they are playing as.

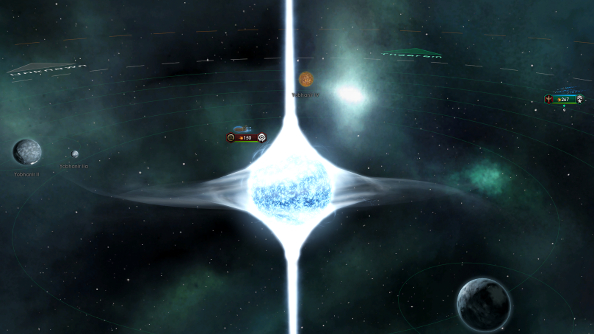

I found myself asking a lot of questions to the mirror while playing Stellaris. Do I want a species that can sail through the stars, unrestricted, using warp technology? Or would I rather use flashy, instantaneous travel through wormholes that I need to actually construct? Or maybe I’ll use hyperlanes that spread out like a web in space. In any other game, I’d be stuck with one, but all three are options in Stellaris, and each come with their own unique strengths, weaknesses and counters. Wormhole gates can be destroyed. Warp is slow. Hyperlanes force you to be more predictable. There’s a lot to worry about.

Any sort of star ruler fantasy you have can be played out in Stellaris. You can interfere with primitive species, doing experiments on them, infiltrating their government, giving them advanced technology… making crop circles. You can enslave entire empires – even your own – and force them to build monuments to your might. You can be Starfleet, the Galactic Empire, whatever the hell the Banking Guild was. Choosing what space dreams you want to live out is is empowering, sure, but it’s the way the galaxy reacts to these ambitions and choices that elevates Stellaris beyond some of its contemporaries.

Let’s go back the our pals, the Psaurions. They had finally discovered how to colonise arctic worlds. This was partially luck, partially the plan. You see, you can research three technologies simultaneously, split between social, physics and engineering paths. And you select them from a list of three, initially, but it can be expanded later. So at first, you have nine techs to research. The game selects what it offers you partially based on your government’s ethics, but also other decisions you’ve made, and partially randomly. The deck is then reshuffled when you choose what tech to study.

This keeps research as a steady stream of surprises, but can sometimes really put a spanner in the works when you desperately need to upgrade your ships but the right option just isn’t popping up. Importantly, though, it avoids the boring cycle of always choosing the same technologies and anally planning all of your research right at the start of the game.

Anyway, Arctic world colonisation was researched, and I shuttled a bunch of colonists off to a lovely, if chilly, new home. I let them get on with it, at first. The planet was in one of my empire’s automated sectors (you can only control a certain number of worlds manually, starting with five), so new buildings were constructed without me needing to be involved, beyond setting a focus. Starports and fleets are not similarly automated in sectors, which does increase the amount of micromanagement (not helped by a click-heavy UI), but also means that you won’t get the AI wasting resources on unnecessary fleets.

I had almost forgotten about my arctic colonists, but then a window popped up. An event! The text explained to me that, to settle this new world, some of the Psaurions were augmented, and this has now led to children being born on the world with genetic mutations. They called themselves Psaurion Mutatis. An off-shoot species had been born. Interesting, right? No. It soon proved to be devastating.

Regular Psaurions and mutants started to clash. The mutants also started to change, evolving and augmenting themselves. They became stronger. Their fertility increased. Violent demonstrations began. Riots plagued the planet. Both groups were just as guilty, and the future for the colony was looking grim. I decided to check in after not hearing from them for a while. The reason became disturbingly clear. There were no more Psaurions left. The mutants had killed and outbred their enemies. And to make matters worse, the racial tension they experienced also made them develop the xenophobic trait. They hate everyone now.

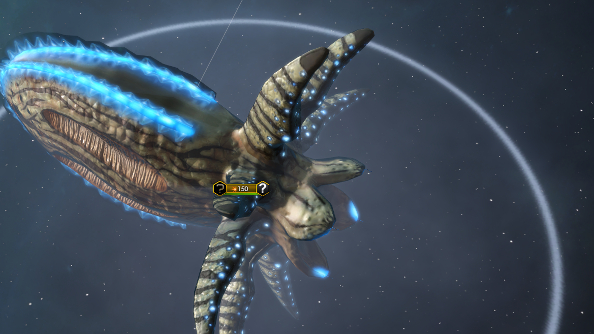

Alongside the semi-random events that breath life and dynamism into the galaxy are quests that will rapidly fill up your situation log, offering up undoubtedly the best writing in any game from the studio, and just as importantly thrusting you out into space to explore further afield. They give purpose to that sometimes overlooked X, making journeys across the stars more than just a hunt for colonisable worlds and more resources.

I’ve searched the other side of the galaxy just to find exotic critters to add to my xeno zoo, and in my quest to understand an ancient race of seemingly evil synthetics, I’ve made deals and bargains with aliens so I can get access to their territory. The quest rewards alone make them worthwhile, often giving big bonuses to research, but it’s their context and the way they push you into diplomacy and even conflict that makes their inclusion so welcome.

And yes, I have declared war on an empire just so I could get a new pet.

War in Stellaris is very Paradox. When you declare war or another species declares war against you, war goals have to be set. You can demand vassalisation, along with the ceding and liberation of planets. The options aren’t as rich as those from EUIV or CK2, but the intent is the same: making defined goals for a war and clear end point. So, vassalisation, for example, is worth 60 war score. Once you hit that number by defeating fleets and conquering planets with orbital bombardments and ground invasions you can offer the vassalisation deal and voila, you now have your very own, disloyal vassal.

Battles themselves play out in real-time on the galactic map, and visually they are an absolute treat compared to Stellaris’ grand strategy predecessors. All the tiny details are on display, from missiles being knocked out by point defense cannons to the different appearances of various projectiles. In action, these scraps look like EVE Online or Sins of a Solar Empire battles, especially when a massive federation goes to war against one of the mighty ‘fallen empires’, with their advanced tech and gargantuan armadas. You’ll probably end up staring at the battle menu more than the fireworks display, though. It’s full of sexy numbers like how much damage you lasers are doing and how much punishment your shields are taking. They give you an idea of what weapons your foes are using, and how you might be able to counter them with another fleet if the battle isn’t going very well.

Building the fleets you’ll be using to duke it out with your horrible alien foes hits that sweet spot between simplicity and freedom. Ship design is purely practical rather than cosmetic, but the list of potential modules can, after a lot of research, become staggering. Ultimately, making these vessels is about balancing the energy need of the ships. Every laser and shield has an energy cost, increasing the number of energy-providing modules while reducing open slots for other things.

While a lot of mods are straight upgrades, others provide more exotic bonuses. A personal favourite of mine is the giant amoeba strike craft. Instead of sending ships from my battleships, I launch aliens at my enemies, which was only possible after completing a quest involving the alien amoebas and then researching the new technology I’d discovered.

War is very much a mid-game thing, and represents a distinct change in pace and tone. In the early part of the game, it’s all about exploration and expansion through colonisation. Your time will be spent doing quests, building up infrastructure, and mapping out a potentially massive galaxy of up to 1,000 stars. At that point, with limited technology and piddly little fleets, wars can be a bit dull, so the dearth of them never feels like an omission. And when they do start flaring up with greater frequency, it’s when the galaxy is ready to do something interesting with them.

It’s when federations are formed that the galaxy really becomes a dangerous place. Federations are like super alliances where leadership is rotated. All it takes is for the current leader to declare war on an enemy on a whim to send everything spiralling down into chaos. It’s lovely. And the aftermath is just as interesting, as power vacuums are left or new empires appear after having their worlds liberated.

During the mid and late game, I do find myself missing the calmer, more optimistic age of exploration. As war becomes more of a focus, events, quests and surprises diminish. This is not to say that the game stagnates, or that there’s nothing new under the sun when you reach this point. It’s just that the rhythm of the game starts to feel more familiar, less novel. Conquest can open up new worlds to you, and thus new events and big space emperor calls that you’ll need to make, but not with the same frequency as the halcyon days of mapping the galaxy.

There are lulls, between wars, where speeding the game up becomes necessary. The lulls always break thanks to some new crisis or conflict, but I don’t think they need to happen at all. The issue, I think, is that there simply isn’t enough to do with other factions. The paucity of options becomes even more obvious if you’d rather not get into a war.

Espionage is essentially non-existent, for instance. Getting information about another empire’s ships and tech usually necessitates a war. All you really know before that is how their fleet strength and tech level compares to your own. A more glaring omission, however, is the lack of trade. Aside from directly selling resources in the diplomacy screen, trade is entirely invisible in Stellaris. No freighters, trade routes, merchants, businesses – this massive section of the economy essentially doesn’t exist.

I don’t want to say, “Oh, it’s fine because anything it lacks will be shored up with DLC,” even if it is probably true. Paradox are prolific DLC developers, and I wouldn’t be surprised to find espionage and an expanded trade system added before too long, hopefully along with quality of life UI improvements like the much needed map modes that are normally integral to a Paradox grand strategy game – the map becomes pretty hard to read once all the empires are rubbing up against each other. But their absence at launch is weird and does make interacting with other empires a bit more perfunctory.

Confession time: I find myself guilty of the critics crime of forgiving a game. I want trade and espionage, I want my dealings with aliens to be more meaningful, but I’m still besotted with massive chunks of Stellaris. Most of it, really. From the stellar (I promised myself I wouldn’t do this, but who was I kidding?) soundtrack to that warm feeling I get when I enslave a whole planet full of cute space turtles, Stellaris offers up a galaxy that I can’t not immerse myself in.

Calling Stellaris Europa Universalis in space is probably reductive, but it was the first thing I did in this review not because they are almost exactly alike, but because, when I put away my empires and get on with my day, the stories that have played out in these digital worlds embed themselves in my brain, and I so desperately want to tell people about them. Both games tickle the part of my brain that wants every battle to have some greater context, every move I make to be part of a larger narrative. Stellaris manages to do this without history to lean on, though, and does so with aplomb.