The Charnel House Trilogy is a short, peculiar adventure game laced with creeping horror. It’s lingered in my mind many times the length of time it took me to get from starting the first chapter, Inhale, to the closing of the third, Exhale. That’s not saying much, I suppose, given the brevity of this curious story in three parts.

I’ve been dwelling on it, anyway. It’s tonally spotty, it wears the skin of an adventure game without ever committing, and its conclusion offers few answers to the game’s many questions. But its atmosphere has its claws in me, and damn do I want those questions answered.

I used to hang around libraries, looking for treasure. I used to – a little bit bored, a little bit unwilling to go back to my boring home – go on these little hunts, with books being my doubloons. I’d call it library archeology if that wasn’t such a silly name.

On these hunts, I wasn’t looking for anything in particular. A weird turn of phrase in the prologue, an interesting author bio, a peculiar cover, maybe even scribbles in the margins. Anything but the plot, really. I wanted a blank slate: no expectations, just a book to dive into and explore, hoping to find something unusual or intriguing.

The Charnel House Trilogy would have been an interesting find, and it’s an argument for treating Steam the same way I used to treat libraries. Going in blind is the best way to appreciate Owl Cave’s unsettling mystery. Even the description on the Steam Store page tells you more than you really should know. I’ll be keeping this fairly vague, then.

The game isn’t a trio of stories, it’s three parts of a whole, and there’s more to come next year. The second act, Sepulchre, actually launched as a standalone in 2013; an enigmatic mini-adventure, light on puzzles, heavy with dialogue and atmosphere. It was fascinating and confusing, but so lacking in context that it was challenging to even ask questions, let alone find answers.

Inhale and Exhale add both context and a sort of conclusion, fleshing the narrative out enough so that now we may at least ask questions, though most answers are still out of our grasp. The three acts are a strange bunch, stranger thanks to the choice of voice actors, most of whom are British (the game’s set in the US) and predominantly writers.

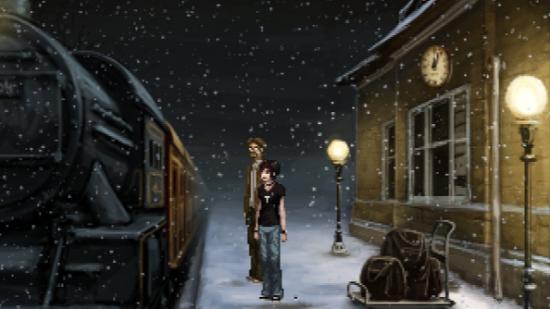

Sepulchre focuses on Harold Lang, an archeologist on an evening train journey that’s infiltrated by a wrongness, infecting an otherwise mundane trip. Before and after Sepulchre, we follow a different character: Alex Davenport, starting with her getting ready to catch the very same train. The final act takes place at the same time as Sepulchre, but from Alex’s perspective.

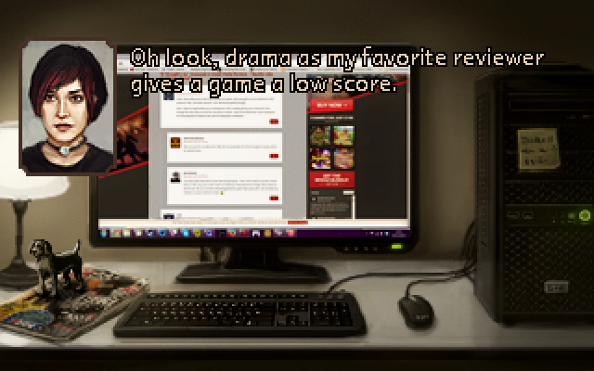

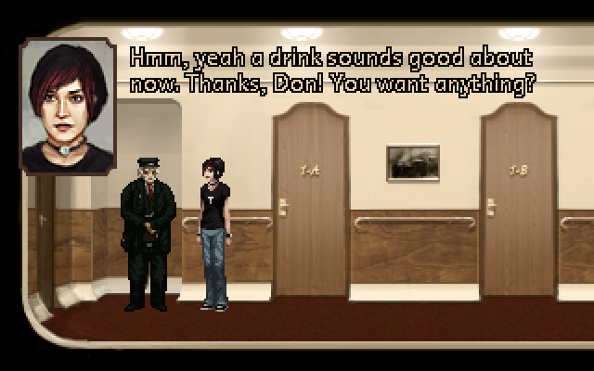

The new chapters don’t always sit comfortably with Sepulchre, though. Especially Inhale. Most of it takes place in Alex’s apartment, and though it slowly starts to build more of the tension that permeates throughout the later acts, it’s also awkwardly meta and referential. Alex talks about her favourite game reviewer giving a game a low score, makes comments about BioShock and Objectivism, and the other two other voices you’ll hear in this act are reviewer and YouTuber Jim Sterling and journalist Cara Ellison, playing creepy neighbor Rob and a radio host, respectively.

It all feels very out of place in this horror mystery, and makes the transition to Sepulchre, a slice of lonely gothic horror, rather jarring. The levity of Inhale is thrown out the window, replaced with the oppressive sense that something terrible is coming.

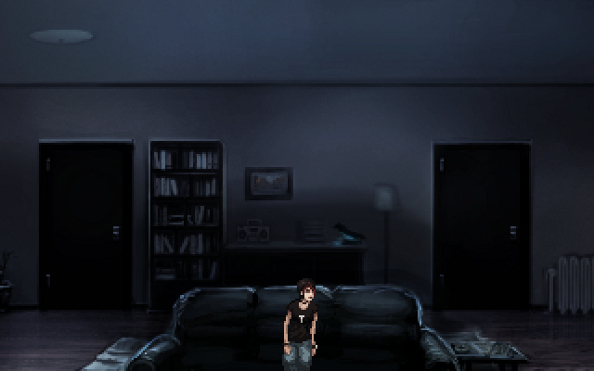

Inhale’s really just an iffy prologue that sets a few things up for later on, and even though it’s only 20 minutes in length, it’s probably a lot longer than it needs to be. Sepulchre and Exhale thankfully shed most of the prologue’s awkwardness, though there still isn’t a consistent tone. That mostly stems from the differences between Harold and Alex; one’s an academic with a stick firmly planted in his rear, while the other is a friendly but depressed 20-something.

There’s also a bit of disparity caused by Owl Cave developing the middle act first. While all three parts suffer from poor audio quality – not the music, which is fantastic, but the dialogue – it’s clear that the newer acts have had a little bit more attention paid to them (though I actually think that Sepulchre is by far the strongest of the three, despite this).

Alex’s apartment, for instance, offers a lot more interactivity, with some extra touches that bring it to life. There’s her PC, for instance, which, when turned on, makes that immediately familiar hum, only ceasing when she switches it off. Alex is also chattier, and has a greater range of comments when you click on objects scattered around the environment. Harold is often relegated to repeating the same kinds of “I can’t do that” phrases, while Alex’s responses are a lot more colourful.

Sepulchre and Exhale take place on the same train, at the same time, but they draw from very different approaches to horror. Sepulchre’s the subtlist of the two, with horror that’s suggested more than shown, whereas Exhale plays with violence, body horror and more shocking reveals. It’s unusual to experience them back to back, but I think the style of horror the characters face is really a good reflection of who they are. Alex and Harold both face something personal, and thus quite different.

The inventory and art will make you think it’s an adventure game, but this is only true in the absolute loosest sense. While The Charnel House Trilogy does actually have puzzles, they are rote, mundane obstacles that don’t justify their existence in the least. I call them puzzles, but I probably shouldn’t. I don’t call searching my pockets for my keys a puzzle, and that’s really the level of challenge and sophistication we’re talking about.

The problem with the puzzles isn’t even the lack of challenge, it’s that the obstacles aren’t engaging, and while some of them do draw one’s attention to important, easy to miss information, there are better ways of teasing clues. Owl Cave’s previous adventure game, Richard & Alice (it’s great, by the way) struggled with puzzles too, but at least there was some satisfaction in solving them, a feeling that you’ve moved the game forward. In The Charnel House, they seem more like tests to make sure you’ve been paying attention, or at least read the last line of dialogue.

It is, perhaps, not a very good adventure game, but – and this is despite the first act – it’s a compelling bit of interactive fiction. Uneven, but compelling. I want to know what the deal is with the train’s destination, Augur Peak and… and that’s about the only question I can repeat here because all the other ones that are rattling around my head like a bag of bones are great big bloody spoilers.

6/10

Disclaimer: Jim Sterling, who voices Rob, was my Review Editor at Destructoid, and Cara Ellison, who voices a radio host, has written for PCGN before.