The mid ’90s were an auspicious time for Bethesda. The Skyrim studio cut its teeth making sports and licensed Terminator games before moving into the (at the time) niche territory of RPGs Bethesda’s upper management were initially wary, but The Elder Scrolls: Arena was enough of a success to get a sequel approved, The Elder Scrolls II: Daggerfall, which struck gold for the small studio. The pioneering open-world game was a hit, so work on its sequel, Morrowind, started immediately after, and Bethesda was seemingly on the path to becoming the RPG juggernaut it is today. But there are two forgotten Elder Scrolls games that came first.

Rather than doubling down on what worked so well for Daggerfall, Bethesda took its new flagship series off-piste. An Elder Scrolls Legend: Battlespire (1997) and The Elder Scrolls Adventures – Redguard (1998) were games whose titles hinted that they’d be the start of new Elder Scrolls spin-off series – expanding the IP into a genre-spanning saga. On a leaflet inside the Battlespire box, Bethesda co-founder Christopher Weaver even wrote that “Battlespire is the beginning of a hybrid genre based on your input.”

The question of why today in 2022 we’re not eagerly anticipating the latest Elder Scrolls ‘Legend’ or ‘Adventure’ can probably best be answered by the fact that neither game was that great. But given that these games contributed to the much-anticipated Morrowind being delayed and – according to some – a financial downturn for Bethesda in the late ’90s, perhaps a bigger question is how and why they came to exist in the first place?

Talking to Christopher Weaver and Battlespire (as well as Arena and Daggerfall) creator Julian Le Fay, it seems that not even those who were there have the best memory of making these tangential titles.

Something that Weaver does remember, however, is registration cards, and that they played a big part in Bethesda deciding what to make next. If you grew up after the days when games came in great hulking cardboard boxes filled with tome-like manuals and other toilet-reading materials, registration cards were little questionnaire forms that often came with boxed games to get player feedback on what they wanted next.

“We were basically inventing a recipe as we went along, and we tried to be very responsive to the registration cards that would come in,” Weaver recalls. “And one of the criticisms that we had gotten was that Daggerfall was so large – certain things that we thought were going to initially give people the sense of expanse started having the opposite effect where they were getting tired of seeing the same repeated landscapes all the time.”

From Le Fay’s perspective, Battlespire was very much a side project – something to squeeze in between the ‘bigger’ titles. The game was essentially a hack-and-slash dungeon crawler, albeit before the mechanics really existed to make this feel great in a first-person format. “After the success of Arena, top management pretty much left it to us to decide what to do next,” Le Fay says. “So Todd [Howard] had the opportunity to do Redguard, and I had some time on my hands to start doing Battlespire.”

Battlespire did away with the mainline games’ open worlds, trade, guilds, and levelling systems. It took place mostly in dark hallways and dingy corridors, focusing on what Bethesda at the time called “the best part of Daggerfall – romping through a dungeon and battling creatures”. Of course, contemporary scholars like myself know this was actually one of the worst parts of that game. Battlespire’s seven levels were expansive, mostly underground labyrinths filled with puzzles and battles. There were also some curious platforming sections, in which you jumped by aiming a floating prism at the point you wanted to jump to – awkwardly, the prism constantly moved away from you so you had to get the timing spot on.

Battlespire even had multiplayer – a feature Le Fay wanted to include in Daggerfall before running out of time. However, Le Fay remembers nothing about making it and during our chat had to look at the game code (which is still in his possession) to confirm that he did indeed code it in. When I jokingly suggest that he could use the code to build a Battlespire remaster, he sounds appalled at the prospect. “I wouldn’t go with this code, God I was terrible back then,” he scoffs, “I thought I was great, but then you actually learn about this stuff and realise how much better it could have been.”

At the time, Bethesda declared Battlespire’s engine “on par with the next crop of games like Unreal and Hexen 2,” which was a bold claim given that – unlike those games – Battlespire didn’t take advantage of 3dfx’s pioneering Voodoo 3D accelerators. And while Battlespire didn’t look terrible, it felt mechanically stiff and behind the curve next to other first-person games.

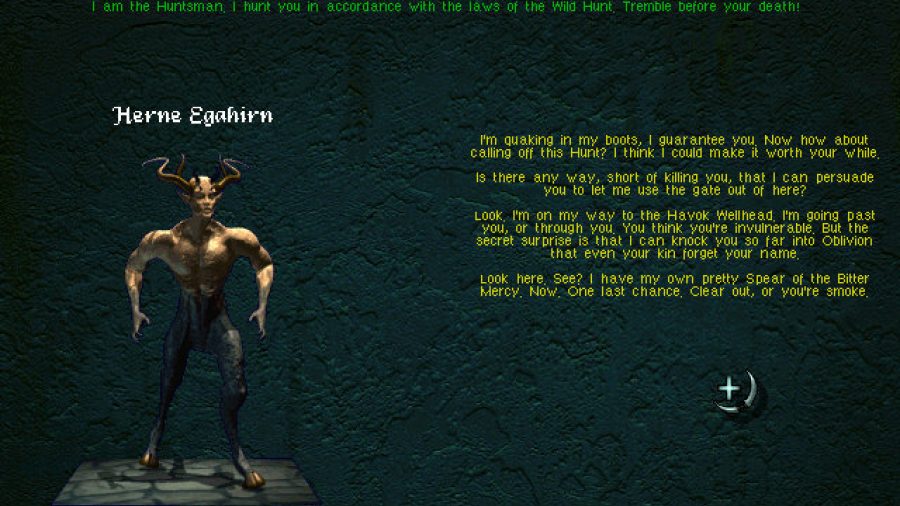

For all its flaws, Battlespire still contained some novel RPG ideas. You could have conversations with many of the monsters in the dungeons, who blabber at you with fully voiced and often amusing dialogue; if the interaction went well, you could avoid a fight, gain some info about how to progress, or even end up doing quests for them.

“Ken Rolston wrote that dialogue and did such a good job with it,” Le Fay tells me. “At one point I remember you’re looking for a key and you ask this scamp for the key and it says, ‘Ooh, it’s in a dark place near my tail – you want to see?’ And you only have one response option: ‘No, thank you.’ He was a very funny writer.”

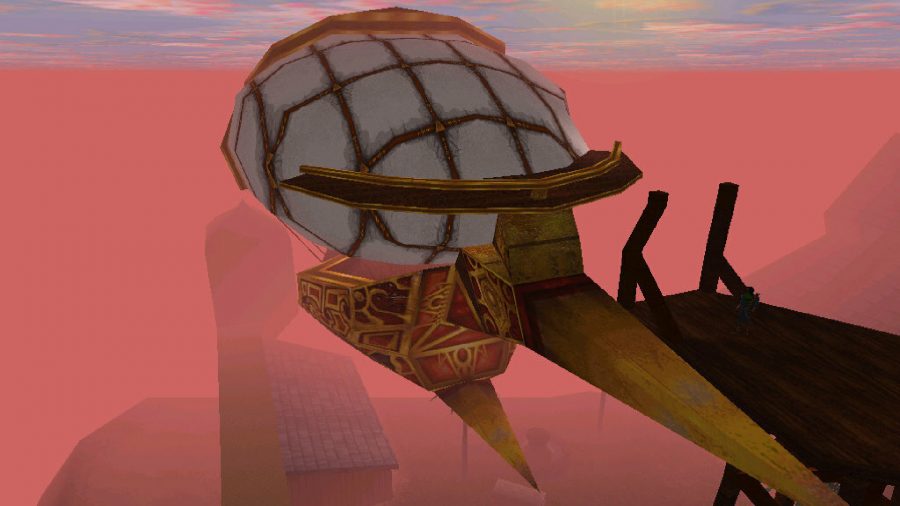

Redguard, meanwhile, was the first and only Elder Scrolls game designed for a third-person perspective. It was a swashbuckling adventure set on a tropical island that was very much muscling into Tomb Raider territory. Critics liked it, even though its rudimentary 3DFX-powered graphics had a low internal framerate which gave it a strange stop-motion quality. Todd Howard took the lead for Redguard, and told German publication Gamestar (via Kotaku) back in 2014 that both it and Battlespire almost spelled catastrophe for Bethesda.

“Daggerfall did fine, then we spread ourselves thin. We started doing a lot of games, and they just weren’t good enough. And they weren’t the kind of games we should’ve been making at the time.

We did Battlespire, I did Redguard—a game I love, but it didn’t do well for the company. So there was this period… Daggerfall was ’96, maybe to 2000, we went through some very rough times. And that was when Bethesda became part of Zenimax, and that gave us kind of a new lease on life, really. And we went into Morrowind.”

Le Fay echoes Howard’s thoughts, adding that Bethesda wasn’t always an easy company to work for. “Neither Battlespire or Redguard took up a large amount of resources, but we were still a small-ish company at the time, so every person mattered a lot,” Le Fay says. “The company also lost employees during that period, including me. It was hard to replace people who have experience with new people who [didn’t] have any sort of comparable experience, even more so considering the relatively low pay at that time.”

Weaver, who was ultimately responsible for co-founding ZeniMax with his friend Robert Altman in 1999, retorts that the idea that Bethesda was nearly ruined by these games, and that the company was saved by ZeniMax during this time was just a rumour among developers, and “utter nonsense.” He does, however, admit that this was a difficult period for the company. “We did overextend on these games,” Weaver reflects, “and we had to cut back as the outflow was more than we wanted to bear and we had some immigration problems with a few key programmers so [we] had to close down one of our larger experimental projects.”

Weaver puts a more positive slant on the two games, saying that while they were never given the resources or time to establish spin-off series, they were vital to Bethesda’s creative growth. “I look at these games not so much as the quizzical offshoots that many from the outside would look at them, like ‘I wonder why they did that?’ Yes, they were completely different, but we were testing theories and giving people internally an opportunity to develop an empiric way to better inform the larger chapters that we were bringing out.”

Beyond the poor sales and what Weaver called – with a wry laugh- “passionate” fan reception where “some people loved what we were doing, some people hated it,” these games also caused The Elder Scrolls III: Morrowind to be delayed. “They tried to synchronise things up to do the next Elder Scrolls and the timing got really messed up,” Le Fay says. “They couldn’t quite get everybody to be free at the same time and that was sort of what pissed me off. That was the final straw for me.”

Directly, it’s hard to see what either Bethesda or gamers gained from these two misadventures. Both Weaver and Le Fay struggle to recall what aspects of these games would go on to inform subsequent Elder Scrolls games, though you could make a case that the condensed island setting of Redguard anticipated Morrowind’s Isle of Vvardenfell – a much smaller but richer and more reactive setting than those of Daggerfall and Arena. Redguard was the first Elder Scrolls game to adopt a ‘less is more’ approach – a philosophy that Howard later implemented in Morrowind. Battlespire meanwhile, was the first game to let players traverse the planes of Oblivion. So who knows? Perhaps they deserve a little more credit than they get.

Battlespire and Redguard marked the end of an era for both Bethesda and the industry at large. With games growing in complexity and cost due to the rise of 3D-accelerated graphics, development teams grew exponentially, and even by the time Morrowind came out in 2002 it was already hard to imagine that just a few years earlier a couple of Elder Scrolls games were created by a handful of developers simply trying out new ideas based on customer feedback.

It wasn’t an easy time for Bethesda or those who worked there, but the missteps and mistakes of this time would eventually bring the studio together for the much-delayed Morrowind. And it goes without saying that Morrowind – easily one of the best RPG games of all time – wouldn’t have been the same game had it come out 18 months after Daggerfall when originally planned. Perhaps the series’ detours into the Oblivion dungeons and tropics of Tamriel were necessary for Bethesda’s treasured series to really find its identity.