It is the near future, and the NASA-like IASA have invented humanity’s first jump drive. To test it, they bring on a ragtag, PR-friendly team to prove that space is for everyone. Among them are an archeologist; a botanist; a blogger; an astronaut recently diagnosed with cancer.

“Shocking nobody,” says The Long Journey Home writer Richard Cobbett, “it goes a bit wrong.”

Want more? These are the finest space games on PC.

The landmark ship is instead catapulted to the other end of the galaxy, where four not-exactly space experts are left to pilot it back to Earth via the scenic route. Will they make it home without accidentally declaring interstellar war, or at the very least, irreparably upsetting a procedurally-generated ecosystem of alien races? Will they bollocks.

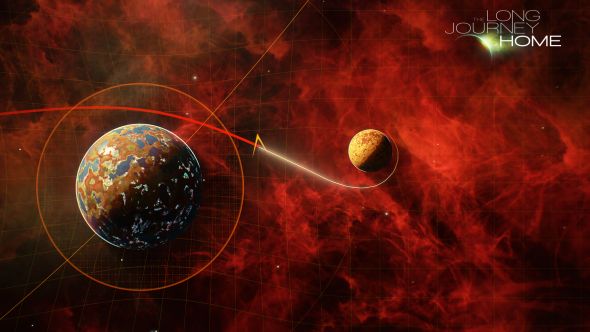

The Long Journey Home comes from Daedalic Entertainment Studio West, the German point-and-click specialists’ largely independent Duesseldorf outpost. Under the direction of Settlers veteran Andreas Suika, they’ve built a game about getting lost and coming home. It sits somewhere between FTL and Star Control 2.

You’re in charge of slingshotting the ship between planets in a top-down perspective, deploying a landing craft in 2D, trading with aliens given random IDs like ‘Little Starkiller’, and fighting in an overhead naval-style view that invites comparison with Sunless Sea.

“We basically give you a universe and a destination,” explains Cobbett. “Everything [after] that point is up to you.”

You have only one life, but to call The Long Journey Home a roguelike doesn’t tell the whole story. Nor does it feel quite right to call it an RPG, despite the trading, factional decision-making and reams of quest dialogue Cobbett is still now stuffing into the game.

“We call it a reverse RPG quite often,” helps Suika. “So at the beginning you have this big fat ship and everything is fine, and then you fall apart and try to keep it somewhat together. That’s the reason you land on planets and try to get resources, and either sell it to aliens or try to fix your ship.”

You’re not going to get home without chatting to aliens. Apart from anything else, they control the jump gates that allow you to travel from one sector to the next. Crucially, however, there’s always more than one gate in a sector – so you’re never stuck pleading with a race who despise you because you fed their ambassador to another faction. For instance.

The idea is that while every decision is imbued with permadeath tension, there are none of the surprise, anvil-drop deaths you might associate with the roguelike genre.

“Not every fight which you have is to the death,” Cobbett points out. “I personally hate that in RPGs. In our game the enemy might surrender, or they might offer you surrender. The traders might ask you to give them some money. The slavers might ask you to give them one of your crew.”

Similarly, if you raise your shields, a militaristic race might take that as a sign of respect – while another might find it unsettling and refuse to negotiate.

“We see everything that you do as communication,” says Suika.

Unreal 4’s openness has allowed for this. Daedalic have been able to stitch not only a unique flight system into the engine, but their own dialogue tools too.

“Andreas basically made the biggest mistake a creative director can make,” says Cobbett. “Which is that he programmed in this system where the crew would have dialogue throughout the course of the game, and he handed it to me, a guy who likes overwriting more than anything else in the world.”

What was first intended as a series of pop-up windows to offer players feedback about their crew’s wellbeing is now a well of Baldur’s Gate II-style back-and-forth banter. Throughout the entire game, your crew natter about each other, previous decisions, and the items you’ve picked up along the way.

“You look at Farscape, Red Dwarf, Battlestar Galactica,” suggests Cobbett. “There are fascinating interactions that happen when people are stuck together in a small space.”

Even when three of the crew have been sold into slavery, killed in fumbled planetary landings or vapourised in combat, there’s dialogue for the sole survivor.

“We want those two sides of the experience,” Cobbett intones. “Yes, the awesome space adventure, but also trapped alone on the edge of death.”

Broadly, though, The Long Journey Home is notable for its lively comms, with characters on and off the ship. That’s embodied in the Insta-style handles picked by the crew. The botanist who likes to get high is ‘IASA Grim Reefer’. The sarcastic archeologist? ‘IASA Snarkiologist’.

“Space games, a lot of them, tend to lack personality,” says Cobbett. “Any point that we can squeeze in a bit more personality we’re taking.”

The Long Journey Home is slated forQ4 2016. Unreal Engine 4 is now free.

In this sponsored series, we’re looking at how game developers are taking advantage of Unreal Engine 4 to create a new generation of PC games. With thanks to Epic Games andDaedalic Entertainment Studio West.