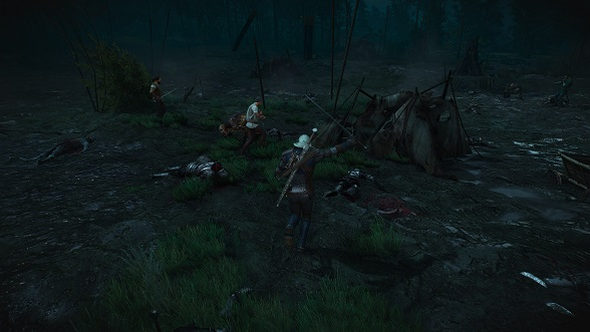

Walk along any bridle path in the Witcher 3’s Velen, and it won’t be long before you come across signs of war. It may be a Nilfgaardian patrol, clad in their black armour and feathered helms, seeking out signs of Redanian incursion. Alternatively, it might be an abandoned cart, robbed by bandits who thrive on the chaos of war, or perhaps by soldiers looking to earn more than medals. Or it may be a battlefield, scattered with hundreds of bodies, prowled by corpse-eating ghouls, ragged banners fluttering in the breeze.

For another side to The Witcher 3, see our sexiest sex games.

Walk a little further, however, and you’ll likely stumble upon a very different scene, a peasant village bustling with activity. Men labouring in the fields, women washing their clothes in wooden basins, children singing and playing in mud-churned alleyways. It’s a bizarre pocket of peace in a devastated land. Yet even here you will spy telltale signs of the wider conflict: a Nilfgaardian garrison stationed to keep order and requisition supplies, a plume of smoke on the horizon, from another village that wasn’t so lucky.

Wherever you go in The Witcher 3, war is never far away. At the same time, you only catch glimpses of it, the remains it has left behind in its terrible, inexorable wake. It is omnipresent and yet unseen, like the vengeance of some wrathful god.This is just one of many reasons why The Witcher 3 is the most striking vision of war ever depicted in a videogame. Whereas in most games we experience war as a cascade of bullets and explosions, or a cold tactical puzzle that must be solved, the Witcher 3 shows us war as a powerful and yet distinctly human force, a sequence of grand plans and calamitous blunders that scorches the landscape and affects everyone from commander to commoner.

How did The Witcher 3’s developer, CD Projekt RED achieve this bold and complex vision? Magdalena Zych, a writer for the studio, explains that the team set out not with the objective of depicting war convincingly, but depicting people convincingly. “As a writer, setting the story in a war-ravaged world is attractive. Especially when working on an open-world game and wanting to populate it with characters who are more than just [a] one-dimensional background for the protagonist. [It’s about] creating a believable and varied society, showing the problems that plague their daily lives. An ongoing war gives us the perfect excuse to set up scenarios that will make the players care.”

The Witcher 3’s war was designed around the individuals caught up in it, and because CD Projekt seek out complexity and ambiguity in each character they write, this layers upwards into the depiction of the war itself. In this game itself, this layering begins with Nilfgaard, not least because it’s Nilfgaard who commence hostilities.

As Nilfgaard are the invading force, in most other games they’d be painted as the player’s enemy. But for the first third of the game, Geralt’s search for Ciri requires him to work alongside, and sometimes directly for, Nilfgaardian soldiers and officers. Through Geralt’s conversations, we come to see them not as some sweeping, malevolent force, but as individuals with their own quirks, hopes and fears. “In one of the first quests, Geralt speaks with a commander of a Nilfgaardian outpost — a man that is tough, but fair and competent, who looks after not only his men, but also civilians of the conquered territory he’s in charge of,” says Zych.

At the same time, CD Projekt strive not to euphemise the actions of either side. Much of the Witcher 3 is about showing unflinchingly the damage done by warring nations to those caught in the middle. Zych cites both the Romans and the Nazi occupation of Poland as inspirations for how the civilians of Velen are affected by Nilfgaard’s invasion. “As Poles, we’ve a strong folk memory of World War II. Even if it’s something we heard from our grandparents or great grandparents, we can relate to people living under foreign occupation. It’s not hard to imagine for us.”

Importantly, the Witcher 3 doesn’t portray the civilians caught up in the war exclusively as victims. Indeed, their responses to the war are just as myriad as those who fight directly in it. “Poverty will force some onto the battlefield and strip corpses of fallen soldiers of their armours and belongings; others will continue to fly the colors of their homeland on tavern walls, even if that country doesn’t exist anymore,” Zych says. “This is what we wanted to show in the game, the different ways in which war affects lives of the people it touches. So we thought about who the characters living in the world of The Witcher 3 are – their needs and fears, where they’re from and what’s important for them – and through their actions show how they’re dealing with the predicament they found themselves in.”

Not all of the themes and images depicted in The Witcher 3 made it in as part of a carefully considered design document. The developers were sometimes surprised by where their approach to a given topic would lead them. One example of this is patriotism. In the Witcher 3, the Kingdom of Temeria has been destroyed by the invading Nilfgaardians, and the Redanians know a similar fate awaits them if Nilfgaard is victorious. CD Projekt decided to pull on this thread, and explore how different people respond when their national identity is under threat.

“Patriotism, which seems like a simple matter, turns out to be quite complex,” says Zych.

Just compare the straightforward attitude of Vernon Roche (a former Temerian Commander turned guerrilla fighter) and that of Sigismund Dijkstra — a man for whom the well being of Redania is close to heart, but whose methods are known to be controversial.”

The Witcher 3 is able to accommodate such a large number of themes and focus on each in detail on account of its sheer size. But the most crucial factor in the Witcher 3’s portrayal of war is not its spatial breadth, but its depiction of time. CD Projekt understand that, in general, wars are mostly made up of long periods of nothing happening, punctuated by short, sharp bouts of fighting. Geralt’s search for Ciri takes place during one of these lulls, when both the Redanians and Nilfgaardians have returned to camp to lick their wounds and puzzle over their next move.

With the battlefields empty except for the dead, life creeps back into the woods and fields. The peasants resume work and traders walk the roads. Hence we experience the war not just as a sequence of battles soldiers either survive or perish in, but as a long-term scenario that is literally lived through by the people who subsist on Velen’s charred strip of no-man’s-land.

What’s more, CD Projekt understand the relative nature of time for various individuals experiencing the war. “Generals who move pawns on a map, are aware of the bigger picture, and for whom a lost battle is not the end of things, will see war differently than soldiers, who lose friends fighting alongside them, or their own life on the battlefield,” Zych explains.

In the Witcher 3, CD Projekt show us the full effect of total war, the devastation it can wreak, and the lives that are destroyed. But it also explores how individuals adapt to it and persist through it at every level of society. “Our goal was to create a believable world and say something true about war and the people that get caught up in it,” Zych summarises. In the end, The Witcher 3’s vision of war is so convincing because CD Projekt portray it as a part of life, rather than a machine of death.