Our Verdict

Torment: Tides of Numenera might have been fuelled by nostalgia but outstrips its contemporary peers in reactivity, writing and invention.

After a long day of intense conversation, my party lay their heads to rest in a tidy hostel on the high cliffs of Sagus – a port for airships where homes slip regularly into the sea.

Though the inn is open to the air and its rooms rest on long stilts that disappear into cloud below, Tranquility’s Rest is the first true calm we’ve found in the bustle and intrigue of the city. Perhaps that’s thanks to Tranquility herself, a honey-voiced proprietor and mutant, stretched tall as if from too many lie-ins. Perhaps it’s the pheromonal perfume she wears.

Since we’re on the subject, here are the best RPGs on the PC.

When we wake, it’s as if our own world has collapsed into the ocean. While we slept, a serial killer has struck again in Sagus’ Underbelly, stripping a casual acquaintance of their life and their skin. Meanwhile, in another questline, adventurers who needed our help were forced to fight a great psychic battle alone. Not all of them made it.

The passage of time, normally the sole preserve of the player to push forward, is just one of the quiet ways in which Torment: Tides of Numenera breaks and remakes the rules of the RPG.

Who knew this bewildering and brilliant game was going to work out? Well: nearly 75,000 backers did. Kickstarter projects have a way of taking the tension out of an outside success story. But it’s true Tides of Numenera didn’t necessarily have much going for it, as a spiritual sequel. Not the wild and impossible Planescape setting, which remains locked away in a tower at Wizards of the Coast. Not Chris Avellone, the man who contributed countless words to the original Torment. In lieu of those things, developers InXile have chosen to inherit vibe, themes, ambition, and a certain frustration with RPG convention.

That’s inherent in the premise, which finds you not chosen for greatness but disposed of. Shed like a snake skin by a body-hopping immortal named the Changing God, your body is a castoff – and your character the consciousness that rushes to fill the God’s space in its head.

Ahead of you, somewhere, are the Changing God and answers. And behind, always following, is the Sorrow – a sort of psychic octopus who relentlessly pursues the Changing God and his castoffs, like some horrific policeman of mortality. The upside is that for you, death is impermanent: a fleeting moment of pain from which you quickly recover and often learn something.

You’re far from the only abandoned thing in the Ninth World. Built on the ruins and technologies of past civilizations, here is a far-future Dark Ages in which the internet is an ancient and little understood form of magic. A city like Sagus Cliffs has its seat of government in a space shuttle encased by rock, while the engines act as forges for the Underbelly below. Even the sand burbles with the grains of degraded machine intelligences.

If that sounds a bit odd, times that by weird, tack on some strange and you’re getting somewhere close to how out there the new Torment is. The Numenera setting – a universe dreamed up by tabletop designer Monte Cook, himself a Torment veteran – proves a wonderful stand-in for Planescape, and InXile have carved out their own corner to have fun in. It’s a place where no side-quest or NPC need be disallowed on the grounds of canon.

In exploring Torment, I’ve met a man whose tattoos map the known world. City guards built from sludge by a machine, itself powered by a single year of each citizen’s lives. A visitant from another world who gave his arms to create his children, as per his race’s reproductive process. The personification of the letter ‘O’. I’ll never see Sesame Street in quite the same light.

It’s important to point out: the experience of playing Torment is at least 75% prose (with the occasional diversion into verse, which isn’t nearly as dreadful as it sounds). If you’ve played Pillars of Eternity or any of the recent Shadowrun games you’ll have some idea of what to expect – but Torment takes it further than either. InXile use the dialogue box as a platform for full descriptive passages: drawing characters in more detail, fleshing out scenarios with threatening postures and revealing tics. Occasionally, they gently enhance the effect using sound, though voice acting is sparse and reserved for key characters. The environments onscreen, vibrant and intricate though they are, serve only as a visual guide to the imagination.

It’s an unusually high burden to place on the player, and that prose won’t be for everyone – I hope you’re up for learning some new or archaic words, like lambent, stentorian or ovoid – but it’s unusually rewarding too, in its novelistic way.

The people and particularly the objects of the Ninth World (the Numenera of the title) are described with wonderful specificity – so that you know what they’re made of, how they make you feel, perhaps even have an inkling of what they might be used for, even if you have no idea how they actually work. This is how Torment stays grounded. Just because something is strikingly weird, doesn’t mean it can’t be tangible – real enough to care about or be afraid of.

It’s an approach not always flawless in its execution. Occasionally the backgrounds will let down the writing with asset reuse. Once in a while, somebody will stay standing up when they should be lying down dead – a source of less confusion in a different setting, you might imagine.

And sometimes, environments can feel too dense, at least for my overloaded mind – exhausting in their array of near-bottomless nodes to plumb for vivid text. Thankfully, InXile tend not to fill their maps with too many unavoidable scripted encounters, leaving you to start up conversation with NPCs whenever you’re ready, tackling the meal at your own pace. It helps that the text attached to those NPCs is always unique and alluring.

The central story, too, is a chain of compelling mysteries that pulls you onwards. Without spoiling anything, it’s a story that provides you with so many different opportunities to be caught on the line, emotionally speaking.

The murder in the Underbelly? That propelled me through later, related events in the main plot and coloured the decisions I made there – providing motivation which wouldn’t have shown up had I not slept in during that particular side-quest. Maybe for you that motivation will come in another series of events I never saw, or the plight of a companion I didn’t pick up. More often than you’d imagine, those smaller stories feed back into the main one, infusing it with personal investment. It’s a super neat trick, and one only The Witcher 3 has managed similarly in recent memory.

If you’ve ever played an RPG and thought of an offbeat solution to a quest – perhaps one that involves something unrelated you know about the world – well, there’s a chance Torment supports that. That kind of thinking is its stock in trade. This is the game for those frustrated by the RPG forever-promise of consequence, the illusion of choice that doesn’t always hold up once you’re seasoned enough in the genre to see the seams.

It would be unparalleled if not for the release of Obsidian’s Tyranny not six months ago – and Tyranny achieved its reactivity by sacrificing overall playtime. That Torment matches it over a much lengthier period goes some way to explaining why it’s been this long in development.

I’ve been umming and erring over whether or not Torment has a pacing problem. If it does, it’s only because it’s advanced outside of its genre’s comfort zone. In a more traditional RPG, combat is part of a loop that breaks up the more dense chunks of storytelling. Torment removes the onus on combat, to its credit – but doesn’t fully replace it with anything.

It’s not for lack of ideas. Torment’s combat is highly accomplished. When it comes around, InXile call it a Crisis – since there’s often a way to resolve a situation via stealth, conversation, or even simply by embracing death and coming back once your enemy’s have moved on. Crises are a turn-based affair resembling Divinity Original Sin, in which each combatant can make one move and one action per turn. Everyone hits hard, and getting the win is often about taking advantage of your quicker companions, who get to go earlier in the queue.

It’s also about making use of your Cyphers: technological oddities which, whether through intent or by accident, have some powerful combat function – healing and buffing allies or reducing your enemies to chemical goo. Carrying too many Cyphers creates unpredictable interference that bestows increasingly negative effects (I met one merchant who had sprouted little claws all over her body, so be warned). It’s a brilliant way of discouraging hoarding. Instead of keeping them for a rainy day that never comes, you throw out Cyphers without hesitation during Crises to turn the tide. As it were.

These are clever, satisfying solutions implemented by seasoned RPG designers who know exactly what annoys them about RPG convention. But a side-effect of that same philosophy means that the Crisis system can wind up underused. Depending on how diplomatically you play, combat can come around very infrequently indeed, and the weapons strapped to your back will see barely any use. In that scenario, Torment can feel like one long improvement on Baldur’s Gate II’s crammed hub city, Athkatla. That might be your dream game. Or, uninterrupted by any text-free combat sequences to cleanse the palette, it might feel like too much of a good thing.

That’s a matter of taste. What I can tell you is that it turns out there’s a power in picking your battles. When I did fight, I did so at the very edge of my abilities, using every trick I’d learned and every gadget in my robes. When I did fight, it was because I’d made a very deliberate choice to do so. Resorting to violence out of revenge, out of desperation, out of malice? That’s a powerful set of feelings, and one RPGs generally rob us of by making combat the default.

Outside Crises, InXile have worked hard to incorporate your party’s skills into conversation. You’ll quickly get used to rolling the dice to see whether or not you’ve succeeded in breaking down a barrier, or persuading a city official to give you the time of day, or dodging a lethal blast from malfunctioning numenera. You’ll select the right companion for the job and spend their skill points as ‘Effort’ to influence the outcome. Just as in Crises, failure can lead to its own intriguing outcomes too. More than anything, Torment rewards curiosity – certainly over good sense or planning. After all, what do the undying have to fear but transdimensional squid beasts with tentacles thicker than your head?

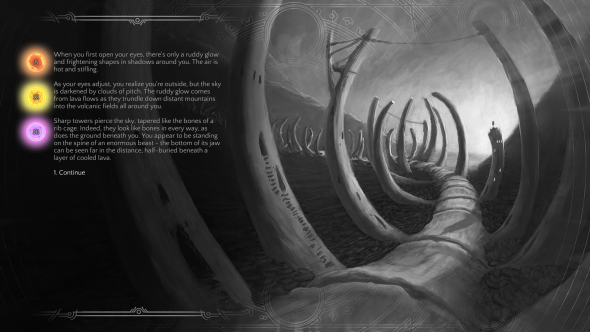

When you do rest, it’s usually not because you need to tend physical wounds, but that you’ve had a hard day’s discovery or diplomacy. There’s more than a touch of the Fighting Fantasy books about the whole thing, and in some senses Torment feels at its purest during the lovingly drawn choose-your-own-adventure sequences that bridge its key story moments.

In a non-linear experience of time that befits the setting, we already know that Torment succeeds. At least 75,000 people are behind it, willing it into being. What’s so delightful is that it succeeds not primarily as a nostalgia exercise but as as a genre-pushing RPG, and a beautifully told story about things left behind.