Creative Assembly is known for its commitment to history, but never has an era defined the shape of a Total War game so much as Three Kingdoms. There are five seasons in-game, just as there were considered to be five in ancient China.

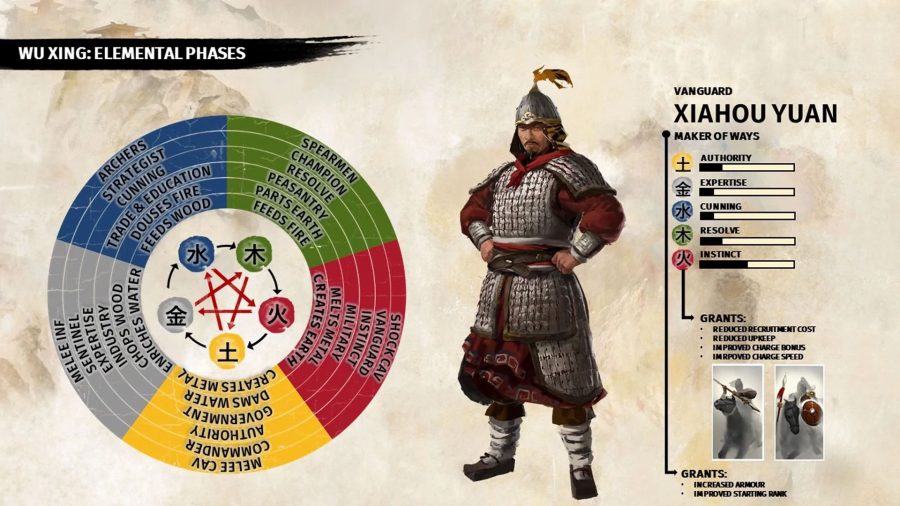

This, together with the series’ traditional rock-paper-scissors approach to unit balancing, are joined under the umbrella of Wu Xing. This ancient Chinese philosophy, made of five transitory elements, underpins and explains the relationships between phenomena at every level of the game, just as it was imagined to do at the time. Even the UI has an inky look, as if the game itself had first been drafted in the second century.

Ironically, it’s these elements that have Three Kingdoms looking like the most modern and ambitious historical Total War in years. After playing the first 30 turns of the campaign, we sat down with art director Pawel Wojs and lead designer Attila Mohácsi to hear about its creation – from the 3D and living campaign map, incorporating parts of the Great Wall, to rivals and nemeses.

And just to step back for a second – yes, the lead designer’s name is Atilla. If there’s ever been an argument for nominative determinism, this is it.

PCGamesN: Three Kingdoms depicts the conceptual system of five interrelating elements known as Wu Xing. How will those elements interact in your game?

Pawel Wojs: It’s this underlying framework, a kind of design philosophy that we applied to the game. It’s not in-your-face, it combines and underpins everything. The ancient Chinese tried to categorise everything into fives – we have five seasons, for example – so everything fits into this framework.

Attila Mohácsi: You will see it in buildings, units, heroes. It’s also helpful for people to get into the game – the fire general, for example, is very good for military buildings, which are red like fire, so you can make that conclusion very quickly.

Wojs: So wood feeds fire, you know? Each element supports another, and destroys another. We use colour to reinforce these relationships, where your Strategists are blue and their skills are that colour, too. It’s a pentagram of relationships, which is why some wood characters will have some water skills or attributes. Each character is made up of five attributes: Vanguards have strong instinct, the fire attribute, while Strategists have the strong water attribute. Some, like Cao Cao, are anomalies with multiple strengths, because they’re legendary.

We’re seeing a lot more of the UI in the current build, with its inky brushstrokes. Were there any special techniques you used to achieve that look?

Wojs: To integrate all of this 2D artwork, we needed ink – we had to develop our own ink shader, which is a material that basically flows and grows with the UI panels. A lot of the ink that you see in the game, in the UI panels, is an ink shader that’s actually using flow maps that were derived from our ink tests and masks that were derived from our actual real ink tests, which is quite cool.

The campaign map is 3D, dotted with steep cliffs and mountains, like that of Total War: Warhammer. In what ways have you developed it?

Wojs: A lot of the artists came onto the team having worked on Warhammer, so they brought with them the skills they learned, but we very much approached it on its own merits. We wanted to recreate China as best we could, and when we looked at other games that were set in China, we were quite surprised that they didn’t really do justice to the Chinese environment.

Related: Play Curse of the Vampire Coast for crabbier strategy

That was one of my biggest pet peeves when I looked at other games. A lot of them are almost just a satellite representation of China’s terrain, so we really wanted to push the beauty and natural diversity of China, because it’s amazing.

We picked some tropey environments present in China that might be isolated to a small area, but expanded them to fill more of the space, just to celebrate the the beauty of those environments. We call out a lot of areas of interest too: you might see mystical mountains, and things like the Yellow River, and these natural landmarks that are present throughout the campaign map.

Parts of the Great Wall were also built during this period as well, right? Are they present?

Wojs: Yeah there are a few there, dotted along the campaign map with a little note telling you what it is. So you can essentially explore China as you’re playing through the campaign.

Mohácsi: As a historical title we also like to give historical information about geography, like what was an important landmark at the time.

You’ve also mentioned historically authentic city designs. How do you ensure that authenticity?

Wojs: We’ve researched a lot. We found quite a few historical layouts that we then used to inform the layout of our cities. There were quite specific north-south-east-west orientations of which way the city should face, for example, so we tried to incorporate that. Not /that much/ is known about this specific period,. I think the most accurate architectural references were Han period clay models found in burial chambers. But as always, we try to research as much as we can.

Mohácsi: We have an epic book about settlement design in this dynasty, about how you make the perfect settlement.

Wojs: Yeah, and one of our layouts is literally the model Han settlement – how the guide book tells you how to construct a settlement. One of our layouts is very much that.

On the note of historical accuracy, you’ve mentioned that one of the things Classic mode does is removes chain mail from characters?

Wojs: Yeah, that’s one of the changes. And weapons, as well.

Mohácsi: For Romance mode, we wanted all these larger than life characters to be true to the Romance of the Three Kingdoms novel, but it does go far away from the history. So we were also saying: ‘we have to deliver this as an historical game, as accurate as we can’. So one of the things that we changed was the chain mail on characters – and their mounts as well – we just removed it, [now] it’s leather. There are also references to huge weapons…

Wojs: Some of which we haven’t even included in Romance, like nine-foot long spears and things like that. It’s great, but it doesn’t work!

The major difference is the impact of generals and the impact of characters on the battlefield. In Romance it’s very much about these legendary characters and the strategy employed with them at the forefront of your battle, whereas in [Classic] it’s more about your individual units protecting your commanders, and playing out the tactics of a more traditional historical Total War game.

On that point, are there any aspects of warfare in the Three Kingdoms period, or distinctive troops or tactics, that distinguish your battles?

Mohácsi: One thing that I believe was quite famous about it was the repeating crossbow guys.

Chu Ko Nu?

Mohácsi: Yes, it was named after Zhuge Liang in some sources. But that’s one of the few things we added that’s very trademark of the era. The other thing is the weapons of this period – one that is really distinct is pretty much a spear with a hook on it.

Another thing we’re trying to incorporate is how formations worked at the time. We have a couple of formations that we haven’t done before, like turtles and circle formations.

Wojs: The Chinese had their very own Testudo, essentially, and they have circle formation, square. So quite a few really cool formations that you can employ if you have a strategist, or a specific item – the items you find throughout the game are far more powerful than they’ve ever been before. One of them is the Art of War, and if you find it – either by capturing it from an enemy or through trade and diplomacy – it you grants you an extra army and several formations that you can use without a strategist, among other benefits.

Mohácsi: We have a couple of legendary items in the game that are quite powerful.

Can you tell us about any others?

Mohácsi: One you might see is Guan Yu’s weapon, the Green Crescent blade.

What, for you, is the most exciting innovation in the Three Kingdoms campaign?

Wojs: For me it’s the way that characters play. The fact they aren’t tied to factions and can move around, that a faction leader can survive and even join you after his faction is destroyed – if your relationship if positive – I think for me that’s the most interesting thing.

Mohácsi: For me it’s character persistence, definitely. That characters leaving others can come join your faction based on the relationship, and the effect that has on diplomacy – you can build up long-lasting relationships with characters, and feel that you will have allies [throughout the game]. It’s unprecedented, I would say, in any Total War game that we’ve done before.

Did you look across the strategy genre for inspiration for these overhauls of the character and diplomacy systems?

Mohácsi: We did look for inspiration, but we weren’t happy with any of the solutions, so we decided to develop our own solution. It’s based on the Romance of the Three Kingdoms novel, and the Records [of the Grand Historian]. That’s the base reference for us instead of anything else.

Read more: March on the best strategy games on PC

Wojs: Just the level of interpersonal interactions, relationships… at this point China was whole, and then it split apart and got fragmented. It’s one country, one nation, you have separated friends, families, everyone essentially knows each other from the major players. So this interpersonal relationship and history is super important. Definitely.