War in videogames tends to be glossy at best: a convenient arena in which engine technology can be touted, power fantasies can be enacted, and toppled foes can be teabagged. Take away the unspeakable horrors of the reality, give it a topcoat of romanticisation, and war is heroic, explosive, and highly competitive. In other words, war in games can be, well, rather gamey.

Games rarely slow down to reflect on what war really means. The human cost, spurious politics, the lives of those surviving amidst the ruins that serve as your playground, and the psychological toils of those fighting it are often absent.

Maybe that is changing a bit. Both Battlefield 1 and Call of Duty: WWII – some of the best World War 2 games – allow for a few moments of introspection (though let’s try to forget about WWII’s Omaha Beach social hub, shall we?). But, for the most part, it has been left to less high-profile studios to ruminate on this subject over the years. I talked with three such developers about how they use the medium to inspire powerful ways of thinking about war.

You might not think L.A. Noire is a war game but, in fact, it’s one of the most authentic ever made.

Cannon Fodder

The first game I remember having a profound emotional effect on me is Cannon Fodder. Specifically, it was the inevitable deaths of the first two recruits in the game, Jools and Jop, and the subsequent knowledge that they were gone for good – their gravestones on the inter-mission recruitment screen an eternal reminder of my failure and their loss.

Not that Jon Hare and the Sensible Software team initially set out to make this innocuous-looking, top-down shooter an anti-war allegory. The game development process looked different in the early ‘90s, and creating a Game With a Message was virtually unheard of.

Starting off with the working title of ‘Lemmings with Weapons’, Cannon Fodder grew, in Hare’s words, “like a sculpture,” starting with the armature of a top-down shooter before gaining its more acerbic appendages. The moment Hare and his team realised their game could contain deeper meaning was when they decided to add the ‘Lost in Service’ screen.

“At first, the mission endings were so cheery, with their victory music and everything,” Hare says. “But the first time we added the ‘Lost in Service’ screen, it hit all of us – ‘Oh shit, look at all these people who died, and you don’t even remember most of their names’. We then made that screen unskippable, so players really absorbed it.”

The recruitment screen in Cannon Fodder is a powerful image – a one-in, one-out production line where fresh army recruits queue up in the foreground while tombstones steadily cover the hill in the background; the living being systematically processed into the dead.

Around the time the tombstones were added, the developers realised that the game (by this point known as Cannon Fodder internally) was tackling something more serious. “By then, we knew this was going to be a game about the waste of war,” Hare says.

Music also plays a big part in Cannon Fodder. At the end of missions, you are hit by the contrast between the triumphalist marching-band jingle and Hare’s melancholy composition ‘Narcissus’ that follows it for the Lost in Service and Recruitment screens. The initial euphoria of victory – which is what most games deliver – is swiftly replaced by grief, as you are confronted with a lengthy sequence showing the cost of that victory.

But, for Hare, Cannon Fodder’s core message is right there in the semi-legendary opening credits song, ‘War has never been so much fun’. “When the song hits the line ‘Go up to your brother, kill him with your gun’, the key word is ‘brother’,” Hare says. “The guy you’re killing is just the same as you.”

Intentionally or not, this manifests itself in the gameplay, where your troops are virtually indistinguishable from the enemy’s, and a single bullet kills you just as easily as it kills them. “In World War II,” Hare continues. “Germans of a certain age were conscripted, and if they refused, it was terrible for them. You can look at war from one side or the other, but the pawns fighting never had much choice.”

This War of Mine

It would be remiss to call this warzone survival game fun. This War of Mine requires you to think expediently rather than giving into the rush of usual gaming impulses. I learned this when one of my party got shot dead during a scavenging mission – in fairness, I was stealing from other desperate survivors.

In response to my man’s death, I flippantly sent out another party member the following night to get revenge for her fallen comrade, but this led to her unceremonious death-by-shotgun too, and my game was as good as over. My emotional instinct for revenge overcame my foremost need to keep people alive, and I paid the price.

The War of Mine senior writer Pawel Miechowski believes that games as an art form have reached a point where they don’t need to pander to the concept of fun that they once did. He cites Spec Ops: The Line as a key influence in that shift. “That game showed us that you can do something more serious, more mature thematically,” he tells me. “It showed that games are capable of more than just speaking to competition, adrenaline, and fun.”

So what is left to compel you to push on? “Just as you have movies like ‘Rambo’, you have movies like ‘The Pianist’,” Miechowski says. “Engagement is the key, especially if you want to portray a drama or tragic story – fun’s the wrong way to describe it.”

Like some dilapidated version of The Sims, you craft objects for your skeletal home in This War of Mine, among them modest luxuries like guitars and alcohol. With the dev team hailing from Poland, many of them have a family member who lived through the privation of war, and understand the importance of these objects of comfort. “I remember when my grandmother told me that to help them survive, they would always be thinking, ‘This will end some day, at some point’,” Miechowski says. “Being human in such hard times is important; people want to mentally run away from what’s going on around them, so that’s why we include vodka, guitars, books, the little things.”

Despite its strong survival genre trappings, Miechowski believes it is too reductive to call This War of Mine a ‘survival game’. “We’re not thinking in terms of genre, but rather a topic,” Miechowski tells me. “This game tries to speak about reality. That was the key message, and everything else revolved around that. We used the gameplay language of the survival genre, but we don’t think of it as a ‘genre’ game.”

Miechowski does not necessarily believe that the big war franchises have a duty to explore the realities of war more than they currently do. More importantly, he thinks it is up to players to remain in touch with the world beyond the four corners of the game screen. “There’s a space for everything as long as the gamer does not forget that it’s a virtual world and that there’s a real war outside that demands respect,” he says.

Valiant Hearts

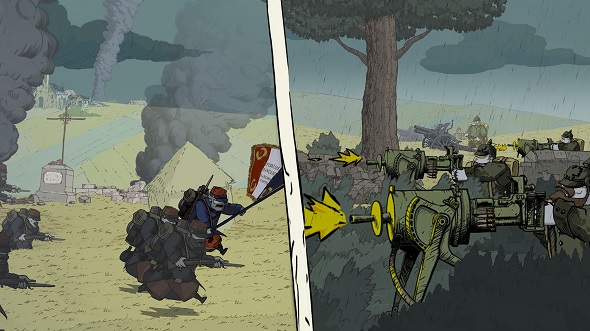

An accessible, endearing and, at times, whimsical puzzler – in which every character has hair covering their eyes like some unkempt sheepdog – isn’t the obvious foundation for a game charting World War I. Valiant Hearts, made by Ubisoft Montpellier, somehow makes it work, telling the story of four people torn away from their loved ones by The Great War, and their heart-rending journeys to be reunited.

You partake in some of the most iconic chapters of the war in Valiant Hearts yet barely spill a drop of blood, with much of the focus being on puzzle-solving rather than combat. Meanwhile, characters bark unintelligible gibberish based loosely on their nationality, so the bulk of the storytelling is through animation, music, and letters.

“The dev team had loads of parents and family involved in the war, and found all these letters from people who’d gone away to battle,” Adrian Lacey, development director at Ubisoft Montpellier, reveals. “You don’t normally get the stories of families, people who’ve lost loved ones or wives, but we found this stuff so powerful; to show how this line was shoved between them for no good reason.”

Valiant Hearts highlights the fragility of long-distance communication during WWI – people were essentially writing into the abyss, not knowing if their words would ever reach their loved ones. “We thought it would be interesting to play on that uncertainty,” Lacey says. This is not only expressed in the characters’ letters, but also in letters you find around levels, which are copies of real ones written during the war.

Behind its innocuous veneer of puzzles and straightforward mechanics, Valiant Hearts is an archive of facts and photography detailing the war, told through collectibles and level introductions. Your animated jaunts across the screen at the Somme or some other battlefield are always contextualised, keeping you in touch with the reality of WWI even as you embrace the fantasy of the game.

There is a distinct lack of violence on your part in Valiant Hearts – is the game missing something by not forcing the player into deadly confrontation in a war infamous for its waste of human life? Wasn’t the the senseless, confusing violence of World War I one of its most vital themes? “We’re always getting bombarded with images of violence today,” Lacey tells me. “We thought it was much more poignant to take that away. It changes the way you think about the character, about your actions. The more we restrict it, the more it makes you think.”

It is not like Valiant Hearts shies away from death, either. All around you, soldiers are being decimated, shot, and gassed, but it is all contextual rather than gratuitous. The war is a vicious backdrop for the tales of love and loss that so many endured during this time, a backdrop that threatens to break into the foreground at any moment and swallow you up under a fusillade of mortar fire.