The Old City: Leviathan is an post-apocalyptic first-person mystery, but in the same way that Symposium is a booze-up or Thus Spoke Zarathustra is about Zarathustra. Surface deep, it’s a slow, disquieting exploration of an industrial complex, absent all interactions but the ability to open doors. Chipping away at the rusty pipes and crumbling mortar, however, reveals something more intriguing.

Through corridors and dreams the game slowly spins its story, a mystery that’s never spelled out. It’s a detective yarn without a case, without a crime; witnesses are journals and torn pages, clues are found in the ramblings of dead philosophers. It’s obtuse, pompous and mostly just bewildering, but damn is it a fascinating puzzle.

Criticising the term “walking simulator” is a bit silly, since – like most perjoratives – it stems from a silly place. But it’s a term that’s almost become genre, moving away from its cheeky origins. It’s still a pretty rubbish name, though. The walking is unimportant, at best ancillary and a way to give a physical element to a journey that’s usually psychological or metaphysical. Perhaps a more appropriate term would be a loneliness simulator.

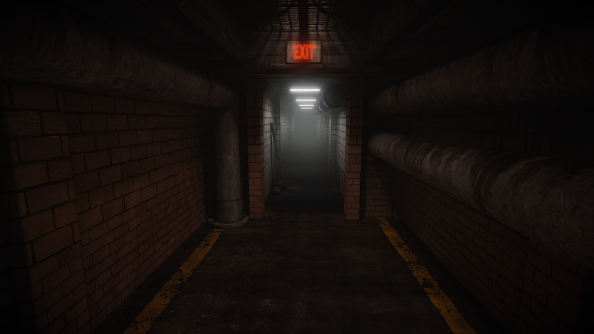

From Dear Esther to The Vanishing of Ethan Carter, loneliness pervades these games, and The Old City is equally as devoid of human life. This emptiness fosters dread and unease, or at the very least gives them a surreal quality; like it’s all a dream, but one floating around the borders of nightmare, bumping up against desiccated cadavers and countless black eyes that peer out of walls.

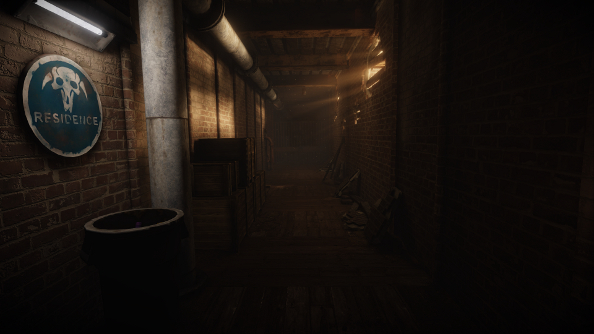

People are echoes and memories in The Old City. They affected the world around them, leaving their mark, but now gone, they are incapable of telling stories. The environment, the bowels of The Old City which players must traverse, and the journals and scraps of paper or the strange symbols painted on so many walls, that’s what creates the ambiguous narrative and slowly unfurls the all encompassing mystery of just what the hell is going on.

At first, the mystery is seductive because it’s so vast. Glimpses into the lives of others are without context, terms and phrases crop up without clear meaning, and the detritus of human civilization is scattered everywhere. Every new piece of information or anecdote just spawns new questions. What is this place? What happened to the world? Who am I?

One discovered journal entry laments the state of the pre-Fall, as in pre-apocalypse, education system. The author, Solomon, is jealous of the reader, because in this new world, knowledge is so scarce that it will drive people to seek it out in a way that never happened when instant access to information was almost ubiquitous. That’s how I felt when attempting to unravel the knotted and tangled threads that make up The Old City.

Nothing is clear at the start, and by the end layers and layers of obfuscation and nonsense as well as philosophy and ethical conundrums make it difficult to make sense of the game. It pushes back instead of giving answers. With no physical puzzles, the only obstacle is narrative itself.

The things you think you want to know start to seem less important, as the game delves into Hebrew mythology, existentialism and Nietzschean philosophy. The former is most prevalent, right down to the few named – and unseen – characters, with names like Abraham and Solomon. Biblical themes are scattered throughout the insides of Leviathan, a presence that is equal parts metaphor and place, itself named after the Hebrew for “whale” as well as the mythological serpent.

Leviathan is also the impetus for the one-sided conversation that’s really between the enigmatic protagonist and the player. He talks to himself, believing he talks to Leviathan, but these chats serve as the only direct pieces of exposition in the whole game. And they’re often just as confusing as the world-building clues and meandering thoughts that punctuate the journey from entrance to big, glowing exit sign.

It’s ambitious and intriguing, but it’s weighed down by the verbosity of the text that needs to be read by anyone remotely interested in finishing the game, particularly if they want even the most slippery understanding of what it’s all about. In The Old City, if something can be said in 10 words, it will be spread out across 50 and nestled in 1,000.

Verbosity itself is not at fault, but it so often devolves into rambling. The fictitious authors of the assorted notes and journals – inexplicably stuck to walls and left neatly on desks – are usually insufferably pompous, to boot. The game is so understated and secretive elsewhere that these often huge blocks of text are overwhelming and awkwardly juxtaposed to an otherwise fairly subtle experience.

It’s just a bit ham-fisted. For all its novel storytelling wizardry, The Old City frequently falls into the trap of letting dry text do a lot of the heavy lifting. Across the 11 acts – all with an endpoint that can be reached within a few minutes, but shouldn’t be – there are times when the written word wins out against the environment, smothering the latter’s voice. It’s like going to a museum where the text descriptions are larger than than the pieces.

On other occasions, the roles are reversed, and the environment is allowed to become expressive. Corpses strewn all over the place, fantastical dreamscapes, the subtle suggestion of terror, it’s an unnerving labyrinth that never quite makes sense. Even when walking through stone corridors or mundane factories, it never seems like a place that was built; it’s more like it sprouted.

Accompanying this is sneaky sound design that leaves you with only the sound of chirping birds one minute, and then a discordant and dreadful tension the next. It’s a quiet game, definitely in the realms of ominously too quiet. I recall countless moments where, in the silence, I turned around just in case someone was following me, which there never was.

It can be completed in an hour, possibly less, but that’s a sprint and won’t reveal many of the game’s secrets. Even fully exploring every nook and cranny will leave questions, and I can’t say that I’ve finished it, myself. I reached the end, discovered all the journals and ended up coming away with a lot of information and a lot of philosophical musings, but distilling it all, piecing it all together, that will take longer. It may very well take another delve into the labyrinth.

The Old City: Leviathan is a puzzle, leaving many pieces scattered around in my brain. It’s not a jigsaw, though, and these pieces don’t have edges that will comfortably fit together. There’s no satisfying click where it all makes complete sense. But that’s what makes figuring it out all the more compelling. Developer PostMod Softworks even warns, at the start of the game, that players are about to enter a broken mind and that what is seen might not be trustworthy.

The possibility that the world is illusory and that what we’re seeing is a lie makes the world impossible to embrace, however. There’s no strong sense of place, and nothing to anchor the high falutin ponderings that make up so much of the game. And even if we were to take it at face value, which seems to be impossible, it’s only a snapshot, a vertical slice of this world without much context, making it hard to reach any solid conclusions. Theories and guesses, though? I’ve got dozens.