When Tim Edwards asked me to do a round-up of PC’s best racing games, I was I was only too happy to oblige. I’m the motorhead around the PCGN virtual office, and the assignment sounded like a blast. One of my favorite genres, and a chance to revisit its greatest recent hits? The only problem was going to be keeping the list to just ten or fifteen items!

Or so I thought. Two days later, my list was a shambles. Somehow, in the last few years, most of my favorite racing games were rendered obsolete. Not by operating system compatibility or changing graphics standards. No, what had killed my racing game collection was Games For Windows, SecuROM, and server shutdowns.

This is how we lose games.

A confession: I was never all that exercised about DRM. Oh, all things being equal, I want DRM-free games. And obviously, I was appalled by things like the Starforce debacle, in which CD-ROM copy protection sometimes ran amok and damaged people’s PCs.

But I never really believed DRM was as dire an issue as it was made out to be. My games worked just fine with DRM and, as the “piracy is killing PC gaming” argument gained currency just through repetition, the odd authentication check or sign-in seemed like a small price to pay.

The issue quieted down. There was never another Starforce disaster, and everything ended up on Steam anyway, which has proven to be a far more reliable archive of my games than any physical media collection I’ve ever owned. DRM didn’t threaten games anymore. The worst we’d have to put up with was an irksome sign-in to GFW or Uplay. I could live with that. It wasn’t ideal, but it worked. Until it didn’t.

No account found

Something has been happening to my games while I wasn’t looking. I noticed it as I started to revisit old racing games to compile a “best of” list.

Actually, let’s not call them old games. They weren’t “old.” I wasn’t firing up IndyCar Racing from Papyrus. I was playing games from the last five or six years. Things that came out in the Steam era, and that I’d assumed would continue to function much as they always had.

But when I went to play Codemasters’ Dirt 3 and Slightly Mad’s Ferrari Racing Legends, I discovered that I couldn’t sign into GFW Live at all. None of my logins worked. Both games allowed me to play without GFW… but then they wouldn’t save any of my progress.

Eventually, I gave up on recovering my account and created a new one using my Microsoft ID. Now, with a brand new account and a working password, I tried to go back.

No dice.

Eventually, a kind soul on Twitter informed me that Games for Windows, in its majesty, does not actually work correctly on Windows 8. I had to uninstall the default client, then go to the GFW website and do a manual download and login via the desktop client. This allowed me, after about three hours of poking and prodding, to play Dirt 3.

What was astonishing is just how bad the resources are for GFW Live. It is practically abandonware at this point. Help pages haven’t been updated in years, and point to resources that don’t exist. Most searches for GFW problems lead to stories about how developers are retroactively stripping it out of their games. As a matter of fact, Codemasters say they are working on getting GFW out of Dirt 3 and replacing it with Steamworks, though there’s no estimated date for when that work will be complete.

The world doesn’t need another story talking about how terrible Games for Windows was and is. That battle is over, and GFW lost. Hardly any new games use it at this point, and even Microsoft seem to have washed their hands of it. But its steady decline has created a new problem: what happens to all the games that used it? Not every studio is going to do what Codemasters and Relic have done in trying to make GFW-free versions of their games. As the service gets ever-more dilapidated, more people will struggle to play the games the GFW games they bought.

Activation roulette

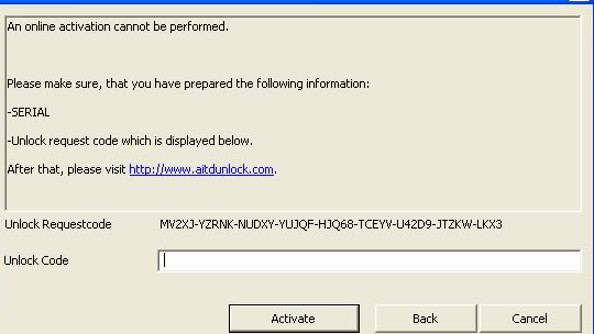

It’s not just a problem with Games for Windows, either. If a game uses SecuROM activation and SecuROM is having an off-day, you’re out of luck. When I installed Test Drive Unlimited 2 off of Steam, I was instantly plunged into a series of problems. First, a SecuROM window popped up asking for my CD-key. But each time I fed it my Steam CD-key, the activation failed.

Then it offered to let me do a manual activation. But in a Kafka-esque touch, it immediately demanded a valid activation key in addition to my CD-key. It seemed that in order to manually activate my game, I’d have to… activate my game.

Oddly enough, when I came back a few hours later and tried again, SecuROM accepted the CD-key. Which is nice… but DRM shouldn’t be this mercurial. A paying customer shouldn’t have to sit around hoping that, eventually, SecuROM will feel like activating a legitimately-purchased game.

Again, SecuROM’s heyday seems to have passed. Fewer games use SecuROM activation, opting instead for Steamworks DRM. But SecuROM was THE preferred DRM system in the mid-2000s. A lot of games from that era are still trying to talk to those servers, even as SecuROM’s future in the industry grows murkier. I have my doubts about whether SecuROM will still be with us in five or ten years, and I am near-certain that its decline will be marked by the kind of worsening service and odd errors that I experienced this week. What happens when your digital, keep-it-forever game is still trying to talk to a relic of the “PC gaming is dead” era?

All of this is bad enough, but nothing seemed quite as pernicious to me as my experience with 2010’s Need for Speed Hot Pursuit, and the the incredibly short lifespan that EA design into their games.

Autologged-off

Hot Pursuit was a major game, and a popular one. After a lot of shaky Need for Speed games, Hot Pursuit brought back the best parts of the cops-and-racers chase scenes that defined the series from its start. It’s also not that dated. It looked amazing in 2010, and it looks terrific now. There’s no reason people shouldn’t still be playing it.

Except that EA put a pillow over its face.

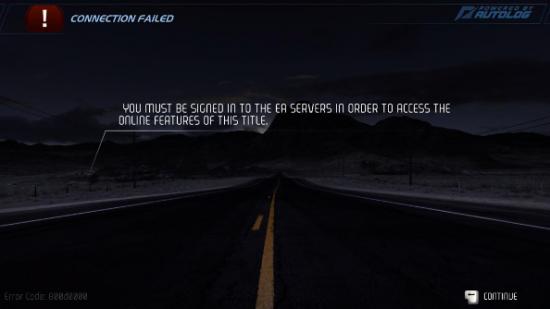

When I launched Hot Pursuit, the first thing the game did was attempt to reach Autolog, EA’s online service for its racing games. Unfortunately, the connection failed because while Autolog still exists, EA disconnected it from Hot Pursuit.

So naturally, the first thing Hot Pursuit wants to tell you in its tutorial is how to use Autolog and all the amazing new features the come along with it. You can post your results and compare them against your friends (nope), find friends to play against (nope), use Hot Pursuit’s robust snapshot feature to take stylish pictures of your racing action (sorry, no), or get additional DLC for the game (hey, bad news about that…).

All but two of the main menu options in Hot Pursuit no longer function because EA turned off Autolog support for Hot Pursuit. It is a fraction of what it was at release after only a few years, because it was built around a temporary service that EA ended.

Even as the days of really intrusive DRM begin to recede, this empty version of “games as services” is what worries me about where PC gaming is headed. Games from major publishers are increasingly designed to connect to social media and sharing platforms. Ubisoft, with Watch Dogs and Assassin’s Creed: Unity, are slowly erasing the difference between single and multiplayer gaming. Watch Dogs’ campaign comes to a halt early in the game so that you can get experience invading another player’s game.

But while these features can be interesting, I also fear they’re a bit of “games as publisher self-service”. Multiplayer is taken away from players and tied to the servers that the publisher operates at will. The idea of the game itself becomes something that can’t entirely be played offline, and likely won’t be preserved. EA have the worst track-record when it comes to actively “sunsetting” their own games, but as Ubisoft make more and more single player and multiplayer hybrids, and more publishers ape their approach, I worry about what today’s games will look like in three or four years.

After a week of trying to play games that I thought would be easy to install and enjoy, games that are not really that old and don’t have Windows compatibility issues, this problem is no longer a hypothetical. It’s happening now, and it threatens the PC’s back catalog. As we stock up on games during the latest Steam Sale, it’s worth asking what we’re really buying, and for how long we’ll have it.