Our Verdict

A story-led shooter that’s heaving with ideas and boasts a distinct sci-fi setting in its doomed USSR. There are cringeworthy moments and occasional design missteps, but the way your abilities and the enemy ecosystem combine is a constant thrill.

The timing couldn’t be worse. Exactly a year on from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, a game with reported investment from and development connections with the Russian state arrives, telling the story of an alternate 20th-century timeline in which the USSR became a hugely advanced technological superpower. Ahead of our Atomic Heart review, there’s been a lot of discussion about the political stance of its developer Mundfish regarding the invasion, reported investment in the studio from companies majority-owned by the Russian government, and a preview event for Russian press last year which some accused of being in extremely poor taste, both stylistically for using USSR imagery, and in its timing coinciding with a global backlash to anti-LGBT laws being passed in Russia.

Another issue is Mundfish’s apparent ambiguity around the Russo-Ukraine war. A statement released on Twitter by the studio in January 2022 raised concerns for not offering clarity on its position regarding the ongoing conflict, though the risk of some form of reprisal that a more full-throated condemnation might invite must be acknowledged.

If this conversation has passed you by, we encourage you to catch up on it before deciding whether to get the game. The situation has been covered in depth by many voices, and although no report offers a categorical insight into the financial beneficiaries of your potential purchase, nor of Mundfish’s political leanings or intentions, it’s all important context.

To complicate matters further, Atomic Heart is very good.

Its creators often cited the BioShock series as an influence during the long lead-up to release. In that series, Irrational Games used 20th century ideologies as a jumping off point to explore historical what ifs, built spellbinding manifestations of those ideologies, and set you down among them, armed with guns and fantastical abilities. And that’s what Mundfish has done too, but likening it to BioShock might actually be selling this game a bit short.

This is a perpetually evolving, shapeshifting FPS game, to a degree that’s almost frightening. Over 20 hours of critical path (and more of optional puzzles and dungeons) it never seems to exhaust its capacity to serve up a thrilling set piece, or a fresh scenario that lends itself perfectly to a new ability you just unlocked. In one moment you’re hurling mustachioed androids up to the ceiling of an aquarium via telekinesis. In the next, you could be mowing down sawblade–wielding robots in a driveable car along a highway, playing a giant game of Snake on a computer screen, or repelling the advances of a predatory weapons vending machine. It’s even got numerous different mechanics for picking a lock. And all of them are enjoyable.

More impressively, they’re all thematically cohesive. I haven’t played a story-driven shooter that feels this thought about, this carefully designed, for years. Catch it in any given frame and you’ll see a strange and vivid world that doesn’t seem to draw from the same references as the rest of the genre. World and gameplay are meshed so well together.

So the story goes, a group of Soviet scientists stumbled upon some rather handy discoveries in the early 20th century which not only turned the tide of World War II but skyrocketed the USSR’s technological advancement – and the world’s. This collective, led by Dr Dmitry Sechenov, developed polymer mimicry adaptation technology that made it easy for the Communist party to roboticise much of the nation’s workforce, and to accelerate human learning to such a degree that university-level training now comes in injection form.

The resulting USSR in Atomic Heart is booming and sickeningly idyllic – for about three and a half minutes. As you drift down a canal in the opening scene, the air’s thick with ticker tape and fireworks. It’s Mass Polymerisation Day – the day everyone gets that injection of smarts. The streets are lined with immaculate greenery and avant-garde architecture looms on the horizon. It’s a vision of prosperity. And then, without explanation or provocation, the robots attack. As one, in an instant. A massacre on a horrifying scale. Only your extensive combat training, Agent P-3, keeps you alive.

It made me think two things, that opening setup. First: it takes time to build a world this rich. There’s so much thought in every corner of Atomic Heart, from the exact mechanisms of the robotic boats upon which you drift down that first canal (and then never see again) to the way its many robotic designs draw from mid-century Soviet animation and Andrey Tarkovsky. The game’s structured so that you progress from one distinct facility to the next, and as you do, the visual language of both the specific building and of the wider regime develop in your mind. It starts to look less alien – but crucially, it’s never anything less than totally distinct from other games. That’s an incredible achievement.

Secondly: anyone looking for an immediate condemnation of the USSR regime, in a similar fashion to BioShock Infinite’s first act reveal, is going to have to look harder. The scientific and political masterminds pulling the strings of this murky robotic mutiny are many, and their motivations and relationships are teased out very gradually. Given the context of this release and the broader discussion around it, that can make the first few hours quite uncomfortable. What is this game trying to say?

I think ultimately there’s a critique of the USSR in there, if not outright opprobrium. Your enemies down at ground level are mindless robots who’ve been hacked, and whoever hacked them is initially framed as a traitor to the glorious regime. Everything would be perfect if it wasn’t for this dissenter. You might consider this glorification of the USSR at first, but over time it becomes clear what the real story is here: human nature eventually undermines any ideology. Ego and pride unpick the scientific progress made in this world, chalking up a horrific body count in the process. Sechenov, his governmental boss Molotov, an idealistic young scientist Petrov and his lover, a talented anatomist Filatova; they all have a vision of a perfect world, and they’re all working to achieve it. It’s just that they’re all pulling in wildly different directions.

P-3’s perspective is one of implicit trust in authority and naivety. The precise reasons for why such a decorated combat vet seems so wet behind the ears when it comes to political affairs and corruption are explained in the back half of the game, but it’s important that you’re witnessing everything through his unquestioning eyes.

(A side note: It’s also eventually revealed why P-3 has such a potty mouth, and seems so tonally at odds with the game he’s in. It’s laudable that there’s a canon explanation for this, but it doesn’t wash away the hours you spend listening to him spouting pure dad-level cringe, and – as with the oversexualised weapons dispenser – there’s a real risk of alienating the player in the early hours as a result.)

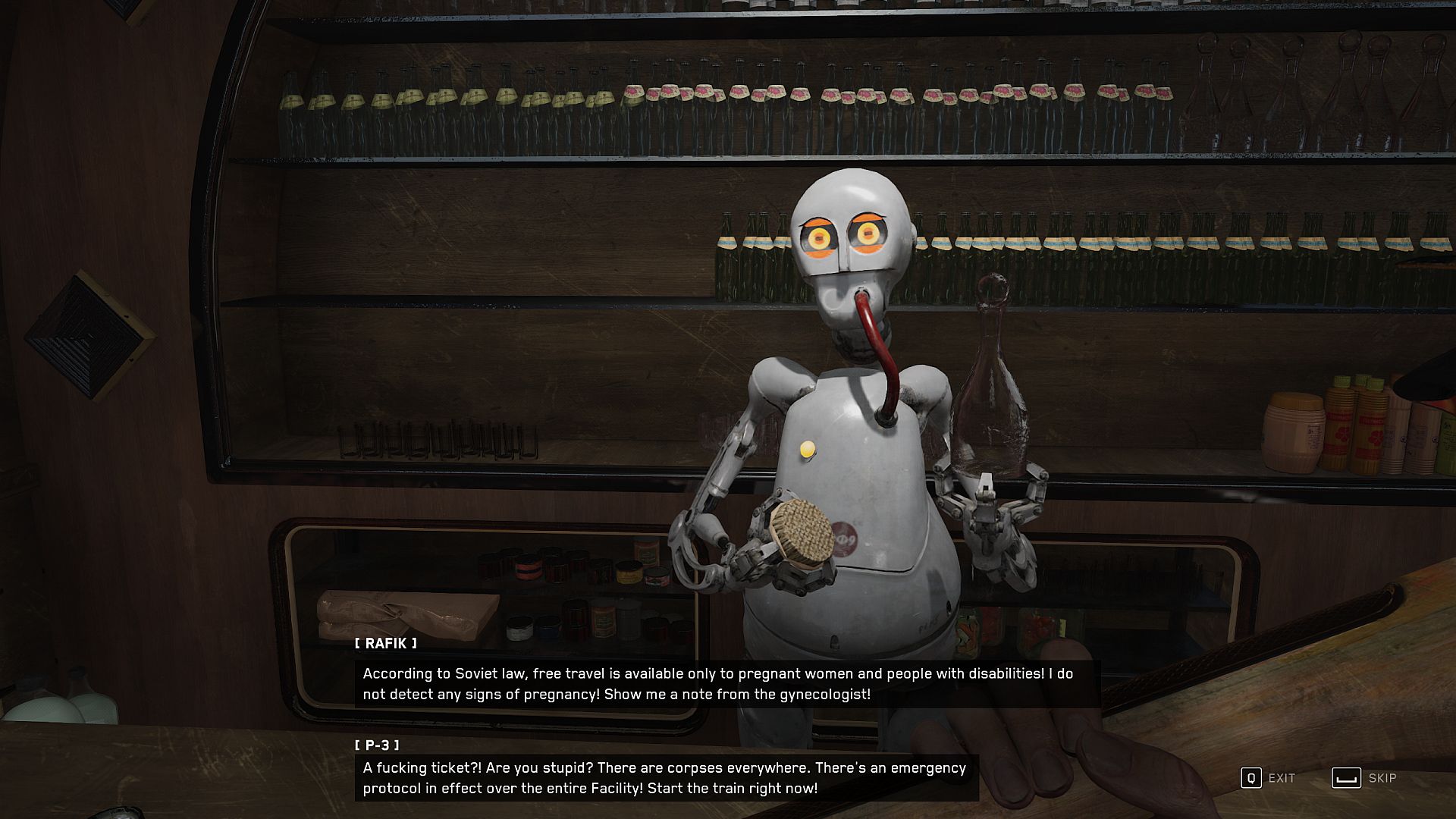

And it’s all set to a backdrop of preposterous bureaucracy. Early on you need to take an automated train from one facility to the next, but you’re halted by an officious metal steward who demands they see your ticket. Only pregnant women and those with disabilities are permitted to travel for free, it tells you, while the entire nation is being razed to the ground in a catastrophic event outside your train carriage.

So you go outside and start asking the local corpses if you can have their tickets – one of the side effects of polymerisation is a preserved consciousness post-mortem, so you have a lot of chinwags with the dead. You take a ticket from a recently expired citizen, only to be informed back on the train that his ticket recently expired, too. Back out you go. It’s Kafka meets CrossCountry trains, and it lends itself to a reading of Atomic Heart as pastiche of 20th Century Soviet Russia.

But when it’s boiled down to even simpler terms than that, it’s a double-act story about an incredibly naive special forces soldier and his glove. Char-Les, your computerised polymer companion, tells you everything about the world you’re seeing around you, filling in all the context and helping you from objective to objective. But he’s also the source of all your polymer powers. When you launch a Shok attack of electric energy, it’s coming from Char-Les’ thin tendrils. When you levitate a room full of marauding machinery and then slam then back down to earth – by far the best ability in a strong array – it’s Char-Les pulling the telekinetic strings. He’s so central to the experience, you even use him to loot. Holding F makes P-3 reach out his gloved left hand and harvest resources for upgrades. It feels like you’re magnetically hoovering rooms clear – drawers and cabinets open, papers and scrap metal flying through the air towards you. Even looting feels good in this game.

Fighting, on the other hand, takes longer to love. Considering the eventual depth and breadth of the combat, it really sandbags at the start of the game, and there’s not much about whacking shiny-faced identical robots with an axe to enthuse about. But two hours later you’re dousing a cornucopia of angry machines in polymer goo, setting them alight, throwing them around in the air and laying into them with rifles, shotguns, and energy weapons. Every time you swap some harvested resources in the aforementioned horny vending machine, you realise there’s a new way to one-two punch enemies with a combination of abilities and weapons. It just keeps expanding.

Should you ever feel nice and comfy, right in the pocket there with all your tried-and-tested procedures for a scrap, the next area you reach pulls you right back to feeling like a scared interloper. It’s not all perfect – there are significant difficulty spikes here, and in large outdoor spaces the decision to essentially make enemies respawn infinitely is a mis-step. The first time you reach a zone where the full Kollectiv 2.0 ecosystem of the robotic assault is in effect, it’s truly daunting. On the ground, Laborer and Lab Tech units patrol. Above them are security cameras that spot and report you, summoning reinforcements. Higher still, Pchela drones roam the sky looking for comrades to repair or humans to decimate. It’s a frightening hierarchy of interconnected enemies. That’s great. But it can’t ever be dismantled in the open world areas – not permanently, at least – so your experience of travelling between facilities is always frantic, beleaguered, and resource-depleting.

Then you run into a boss. Like everything else in Atomic Heart, these all feel completely bespoke when they appear, but very much part of the world in which they’re turning you to puree. They’re often a bit bullet spongey, but they do reward that classic Soulslike rhythm too: brave the onslaught of attacks, dodging according to the patterns you’ve learned, then wait for the vulnerable half-second and let rip. I wasn’t in love with any one of these fights in particular, and here again you’ll find difficulty spikes. I was annihilated several times by Hedgie, a pinball of death that terrorises you in the idyllic gardens of a museum, because at that moment I’d tailored my loadout for close quarters fights: shotgun, polymer goo, Shok. Getting up close to a 20-foot pinball that throws fire in all directions is not advisable.

Salty or not, I was impressed by how well each boss was implemented in a game that’s usually busy being Prey or BioShock. I don’t know if I’ve ever seen enemies of such scale move so quickly before.

If Atomic Heart has one glaring weakness though, it’s the localised English voice acting. It’s not that the performances themselves are toe-curling, or that the translation garbles traditional grammar. It just all sounds incredibly clumsy when it hits your ear. Part of it is the cueing of the line deliveries, which seems to be a technical issue rather than one of performance. Characters talk over each other like they’re paying for the vocal booth by the second, but the bigger issue is that it doesn’t sound like the performers know the game they’re performing in. P-3 is sometimes just a notch of gravelliness away from Duke Nukem, and if I ever hear him say ‘Crispy Critters’ again it’ll be too soon. Mundfish recommends playing with Russian audio and localised subs, so the studio would probably agree it hasn’t aced this aspect of the game.

Frame rate performance has been varied on my 2080 Ti, fluctuating before and after an Nvidia driver update and a sizeable game update on Steam. It’s always been playable on the ultra preset, but not always smooth. However, Nvidia’s DLSS is very effective in smoothing out any frame dips. What I notice instead are the number of independent objects in a given scene when I start chucking things about. I notice how beautiful the slaughter of humanity looks, and how the light bounces off a beheaded robot’s cheek. It’s a gorgeous game, and it doesn’t look immediately recognisable as Unreal 4 tech either. It looks more authored than most releases. Check out Atomic Heart’s system requirements to learn if you can run it.

The fact that Mundfish has delivered such a formidable shooter on its debut release is astonishing. It’s a reminder of how rare it is now to see a story-driven, single-player shooter produced to this high standard. It’s been in development since around 2018, and you really get a sense of that. It feels as though every component part has been considered, reconsidered, and polished. Games like this don’t come cheap, and they take a long time to create.

None of this makes the broader objections and reservations towards the project go away. Given its investors, it’s likely or at the very least possible that some revenue from Atomic Heart’s sales will find their way to the Russian government. The game doesn’t take an explicit political stance, but nor is its content any more tonally worrying than a typical Call Of Duty campaign. CoD is a series which has placed the player in the role of a Russian terrorist shooting unarmed civilians in an airport, and inaccurately depicted the ‘Highway of Death’ incident in the first Iraq war as having been perpetrated by Russia when in fact it was American A-6 Intruder attack jets which instigated it. 2017’s Prey imaged an alternate 20th century timeline in which the USSR became vastly technologically advanced, too, after having made contact with alien life, although Prey’s USSR collaborated very closely with other superpowers, whereas Atomic Heart’s version is an island where “the capitalists” are mentioned only in the context of what they might think of this robotic disaster. In terms of the content itself, Atomic Heart doesn’t exhibit poorer taste or more objectionable politics than its contemporaries.

Still, the conversation surrounding it remains. This review won’t tell you which side of that conversation to fall on, only what it’s about and why it’s happening, and, of course, what lies beyond the main menu screen. The answer to that is an extremely finely crafted shooter. A game with another good idea every ten paces, that can do convincing impressions of Half-Life 2, Portal, Prey, BioShock and Dishonored in the space of one evening. I wish there were more games like it. And I hope they’ll be easier to recommend.

Developer Mundfish has come under increasing scrutiny in recent weeks after it was alleged that the Russian government stands to gain financially from the release of Atomic Heart. This is due to the fact that investors involved in financing Mundfish include GEM Capital, an investment fund whose founder has ties to Gazprom and VTB Bank, both of which are majority-owned by the Russian state, and because Mundfish is partnering with VK (formerly Mail.Ru) for the Russian release of Atomic Heart, evading sanctions on Steam. VK is also majority-owned by the Russian state through Gazprombank. Further, Mundfish’s CEO is a former Creative Director at Mail.Ru.

With Russia’s ongoing invasion of Ukraine, many players are choosing to boycott the game in protest and donate money to organisations like The Ukraine Crisis Appeal, International Rescue Committee, and the British Red Cross.