It’s apt that Baldur’s Gate III, the latest in the series that did so much to define the modern CRPG, seems poised to redefine it.

Yes, as the leaked screenshots show (you can view a full gallery of all 33 new screens below), certain UI touches are reminiscent of developer Larian’s recent hit Divinity: Original Sin II, but the Belgian studio is not resting on its laurels. Ambition to match this long-dormant, iconic IP runs through this game at every level.

“We have changed so much tech – we have certain ways of doing textures like subsurface, all the buzzwords from game tech – we start implementing them into our engine, and all of a sudden it’s 60% new and only 40% known and proven,” senior producer David Walgrave says. “I thought we were changing too much, but at the same time we increased our team size so much – we’re at least 300 now, with outsourcers – and the production value of Baldur’s Gate III needs to be that high so we can make this a truly triple-A game.”

The consequences are immediately clear when Larian CEO Swen Vincke fires up Baldur’s Gate III in a dungeonesque rock club in Paris, where I can’t tell which skulls and torture equipment were brought in for the press event and which were here already. When the game begins, the camera is in isometric view, and with those familiar UI elements, it looks like a grittier, more realistic DOS2. But then Vincke brings the camera down into third-person mode, and Baldur’s Gate III looks like a modern Dragon Age.

“The camera can go into third-person with the mouse wheel,” Vincke says, or you can stay in isometric, in which case you can freely zoom and rotate. “There are certain choices we’re making because it’s 2020, and we know it’s Baldur’s Gate III,” Walgrave says, when asked about this. I doubt anyone would’ve begrudged Larian the decision to stay in isometric view – it defined this genre and it doesn’t stop a game from being brilliant, as DOS2 emphatically proved – but had the team done so, “we’re not going to be proud of ourselves, and we won’t have built our technology, knowledge, or experience,” Walgrave says. For me watching this demo, it’s an early statement of Larian’s intent.

Turn-based or not? Here’s the lowdown on Baldur’s Gate 3’s combat

Whatever else this ambition means for the trappings of genre, you can still make many confident assumptions about setting, gameplay, and systems, because this is still a D&D game. Larian’s reassuring fidelity to the source material is the second constant of Baldur’s Gate III, running alongside its iconoclastic ambition at every level, from the obvious and essential – character creation is based on D&D races and backgrounds, combat is based on D&D rules – to the merely flavourful and possibly unnecessary, like the little red D20 that pops up on screen for you to click and roll when attempting a skill check.

We’re playing as Astarion, an unctuous high elf rogue who also happens to be a vampire spawn. As you can see in the opening cinematic above, we’ve been captured by a mind flayer named The Absolute, and implanted with an horrific tadpole that burrows under our eyeball. Having taken control of the Nautiloid – that’s the Absolute’s gross tentacley ship – we’ve crash landed on the Sword Coast near the river Chionthar, about 200 miles to the east of Baldur’s Gate.

Ordinarily, mind flayers use those tadpoles to reproduce, but when after a few hours we don’t start vomiting teeth to grow tentacles, it’s clear something is different this time. Indeed, the tadpole seems to be a bit of a boon. DOS2 makes its presence felt again as Astarion wakes on sun-dappled sand in the wreckage of a ship, seeking fellow survivors, but as a vampire spawn, he ought to burn in the sunlight and be unable to cross the running water of the river’s tributaries. He makes plenty of unique, fully voiced, characterful observations – “was the sky always this blue?”, “what a waste of perfectly good blood” – before stumbling upon Shadowheart, a sardonic, permanently unimpressed half-elf cleric, who is struggling to get into a door at the base of a cliff.

DOS2 yields to Dragon Age as we zoom to a frontal view of Shadowheart’s detailed and intricately animated face. The blending between animations still needs a lot of work – the game is still pre-Alpha, Vincke says – but individually there are some amazing details. Shadowheart is able to wrinkle her nose in disgust and arch her eyebrows while keeping her eyelids half open, conveying note-perfect and utterly withering disdain.

The conversation has barely started when we get a glimpse into her mind, memories, and feelings – the tadpole enables us to “mind meld” with others, says Vincke, and later will even allow us to influence them, and more, typically requiring only easy skill checks to pass. When our dialogue options pop up, one that’s unique to Astarion (as in DOS2, there will be unique options for race, background, and so on) is the opportunity to feed on her. This would turn her hostile right away – understandably – and remove her as a companion for the rest of the game.

Bang, or not? Here’s what we know of Baldur’s Gate 3’s companions

Instead, we try this later in the demo while resting at camp, which serves as a long rest does in D&D. You can elect to camp at any time when not in a dungeon or in combat, and lots of rich lore-related events can take place here. Story cutscenes can occur; deep, probing conversations with your companions can be had; and when you go to sleep you can ‘reflect’ on your situation, making skill checks against your own attributes – wisdom or intelligence, say – to either come to some epiphany or just toss and turn uselessly. But we’re here to suck some blood.

Vincke assures us there are some “very evil paths in the game” as we go to feed on Shadowheart. It’s a very high dexterity check – 18 – but the little red d20 settles on 20, and then we pass an easier discipline check to stop ourselves from draining her dry. When we chat with her next morning, she’s none the wiser, but complains about feeling “run down” and will suffer -1 to all attack rolls for the ‘Bloodless’ status effect. Vincke says the party will later discover that Astarion is a vampire, and there will be “heavy consequences” when they do, should you have fed on any of them. For now, though, he’s thrilled – feeding on thinking creatures was an act explicitly banned by his master.

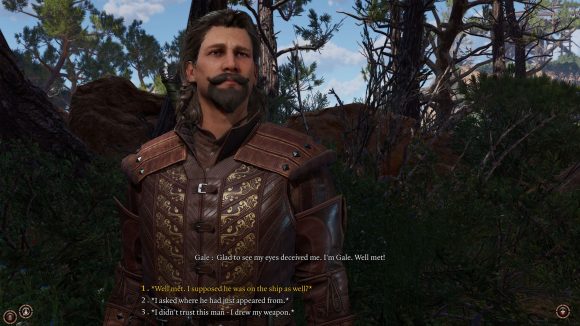

As we explore the canyons around the river the next day, we pick up another companion – a smug wizard named Gale, who is spot-on patronising as he tilts his head forward, furrowing his forehead with a single raised eyebow – and scrap with a gang of bandits as we explore the Lost Chapel of Selûne, our first dungeon.

Vincke prepares for the first fight by unchaining Astarion from the group and sneaking him behind an archer. An icon indicates whether he’s lightly obscured, fully obscured, or in a clear area. As in DOS2, a red overlay on the terrain indicates enemy lines of sight, though sneaking characters will move at a crouch like boring real life, rather than tip-toeing under barrels or rocks. Astarion kicks things off by shoving the hapless archer off his perch to plop onto the stairs of the dungeon below. It’s hilarious and I will sub to the first streamer who attempts a shove-only BG3 challenge run.

Sadly everything goes to shit for Vincke at this point, as he fails roll after roll and Larian’s refined “AI 3.0” proves cleverer than anticipated, refusing to pursue a fleeing Astarion in order to mercilessly execute the downed Gale and Shadowheart (as in D&D, downed characters will make death saving throws each turn – three fails means you’re properly dead). But Vincke takes the chance to show off BG3’s adaptability: plan A is to spread the contents of an oil barrel beneath a pair of bandits and ignite it, but he fails to do enough damage to break the barrel. He improvises a new plan: hiding behind a door, shooting out of it, then closing it again before the enemy returns fire. He solos the fight and suffers no damage.

You can read more about combat in our separate story here, but to answer the big question: it’s turn-based, as in D&D and DOS2, though there’s one important change from both in that initiative is in group, not individual, order. Larian says this will make combat faster than DOS2, “because you can control your entire group at once and then the entire enemy group acts” (or vice versa – you’ll roll initiative to determine who goes first, as is proper). Real-time with pause is not an option.

Excitingly, you can also enter turn-based mode when you’re not in combat – similarly to pausing in the original Baldur’s Gates – with each ‘turn’ equating to six seconds as in D&D. This is useful if you’re approaching a non-combat challenge that requires precision timing and movement, as Vincke elegantly demonstrates by steering Astarion around a fireball trap, before getting blown up by the next.

Resurrected via cheat code, Gale and Shadowheart come to revive Astarion via a resurrection scroll. While they’re elsewhere in the level they move in real-time, but they enter turn-based mode when they approach Astarion. This is how it’ll work in co-op multiplayer, which is definitely happening. Walgrave says “we don’t know yet” if the game will have a Dungeon Master mode, but that “we want to”.

We escape the dungeon and are welcomed into the game’s first hub area, a pleasant camp nestled among canyon foliage, run by a group of Tieflings. Vincke has a poke around, discovering a hidden path into a locked building. To get there, he has to edge along a cliff, build a staircase by stacking crates on top of each other, and jump up and down several elevations. Vincke promises that “exploration is always rewarded, and it will take you much, much further than you would ever expect” – it’ll lead to whole areas containing big adventures that can easily be missed. The verticality of the level designs is a constant throughout this demo, with implications in most major fights – in the final encounter, for instance, Vincke uses exploding barrels to knock a hobgoblin down through two elevations into a spider’s nest.

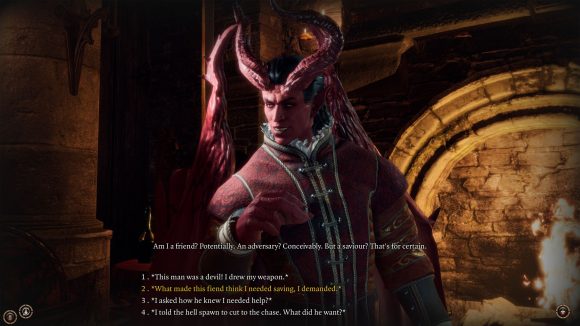

It’s also in this camp that we get our first hints of story. The local goblins have abandoned their god, Maglubiyet, to serve the Absolute, whose representative in these parts is a vindictive Drow priestess. She wants the camp wiped out, and when we come to deal with her, the game will facilitate a huge number of solutions: fight her straight up, negotiate, cooperate and betray, or even cooperate entirely and gain her confidence. It seems to be the first major inflection point, and that it should come so early with so many solutions is mind-boggling if the rest of the game will take the same approach.

This information comes from a captive goblin, who we can interrogate in several ways. One of these is by talking to her corpse (yes, dead-speaking is back), another is via the tadpole’s psychic powers – but Walgrave cautions there will be a price for using such gifts: “It’s like you’re giving into it”. It’s not clear yet what this means – perhaps you will turn into a mind flayer – but at the very least I’m guessing it’s part of the Absolute’s plan, which means nothing good. For Astarion in particular, who can thank the tadpole not only for his psychic powers but for being able to walk in the sun and defy his master’s rules, “it’s a very tough choice – am I going to go for or against it?” By contrast, another playable character, Lae’zel, is a Githyanki – one of a people who were enslaved by the mind flayers. For her, “it’s not a big decision – she just wants to get rid of the thing.”

If this sounds familiar to Baldur’s Gate veterans, that’s by design. Just as you could embrace or resist your powers as a Bhaalspawn, so too can you embrace or resist the tadpole in Baldur’s Gate III. While everything that happened in the original games is canon in D&D, and therefore canon in BG3, it’s this duality, this “theme and philosophy” as Walgrave says, that makes this a true sequel.

It probably couldn’t have been any other way. It’s been 20 years since the last numbered Baldur’s Gate, and the worlds of both the Forgotten Realms and of CRPGs have moved on – the latter advanced by Larian as much as anyone else. It’s time for a new story, and for a new paradigm for the entire genre. This is no less than what Baldur’s Gate III is aiming to achieve. I can’t wait to get my hands on it, and we’ll all get our chance when it hits early access later this year.