In many ways, Cyberpunk 2077 is a story about the ways people distract themselves from misery, and how these distractions can be exploited by the people responsible for that misery in the first place. Bread and circuses might be replaced by grenade-nose clowns and lab-grown SCOP, but the people still need entertaining, and the game’s most memorable side-quests keep this in focus.

There’s the televised martyrdom of ‘Sinnerman’, the rock and roll camaraderie of the Samurai reunion, but most poignant of all, there’s Afterlife bartender Claire’s deadly street races. This series of races tells a story about Claire herself, about what drives her, and what keeps her up at night. To talk about them properly, though, we first need to talk about the trope of dystopian death sports.

Roman gladiatorial combat has been in our collective consciousness for a very long time, but do our current visions of state-sanctioned blood sport have an origin point? A lot of mine can be traced back to two novels written by a young Stephen King. The Long Walk, published in 1979 under the alias Richard Bachman, is based around a walking contest in which any participant who slows their pace for a few minutes or stops to tie their shoelaces gets a bullet. Brutal stuff.

The novel’s real impact on pop culture wouldn’t be seen for another 20 years, however, when another story influenced by King’s depiction of a totalitarian government-led sporting event was published: Koushun Takami’s Battle Royale. Takami credited King’s work as helping to refine a nightmare he’d had that inspired the book, and King would later praise Battle Royale as “insanely entertaining”.

Not content with inadvertently sowing the seeds for PUBG and Fortnite, King also published The Running Man in 1983, the Arnie-fronted 1987 film adaption of which would inspire 1990 arcade classic Smash TV. The movie also has another link with Takami’s Battle Royale: the use of exploding collars to keep captives compliant, which has become another dystopian staple.

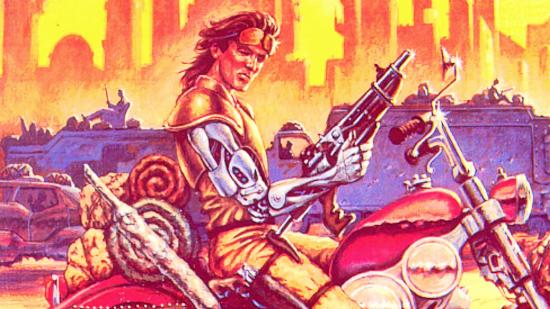

So, do we blame it all on King and call it a day? Not quite. 1975, four years before The Long Walk was published, saw the release of two cult classics about violent dystopian sports: Norman Jewison’s Rollerball and Roger Corman’s Death Race 2000. Rollerball’s premise went on to inspire a slew of early games, but Death Race 2000’s is keenly felt in everything from Carmageddon (which was originally an official adaptation) to Road Rash and Destruction Derby. Gaming of course proliferates its own influences. If something works, we see it more, until context or inspiration becomes almost meaningless.

Before we move on, though, it’s worth mentioning a 1953 short story by Robert Sheckley called ‘Seventh Victim’, since its concern with a dystopian human hunting game called ‘The Big Hunt’ predates everything we’ve touched on so far. Also, this is all an admittedly Americanised reading of canon, but it does ground us somewhat.

Anyway, videogames. As a rule, we see these dystopian sports used in gaming in a couple of ways. There’s the largely inconsequential playground of something like GTA 5’s Arena War, where a disregard for human life combines with gladiatorial framing to offer an ideal excuse for ‘damage things, get points’ gameplay. Both games and their critics (myself included) are constantly having crisis-level flaps about dissonant depictions of ultraviolence, and blood sports handily offer clear winners, losers, and, most graciously, a narrative reason for a number going up every time you hurt something.

Then there’s the heavier, chin-stroking presentation: games that borrow some of the thematic concerns of Running Man and Death Race 2000 and pair them with the evergreen allure of ‘haha spiky cars go brrr’. One such game was 1997’s Rock n’ Roll Racing 2: Red Asphalt. It was a middling sequel to one of Blizzard Entertainment’s most underrated games, but its brief story did a good job of selling a seriously oppressive universe. Televised vehicular slaughter kept the conquered masses of an entire solar system docile, and losing too many races sent you back to a prison barge for a lifetime of forced labour. Also, the cars are very spiky, and yes, they go brrr.

Read more: The best cyberpunk games on PC

Claire’s quest chain in Cyberpunk 2077 is a superb slice of world building. It takes a familiar sort of open-world distraction, and ends up telling us a fair amount about both Claire and how law in Night City operates. It’s a far more ad-hoc, disorganised take on the usually Superbowl-inspired murder sports we see in similar settings. It shows us that Night City’s residents are willing to risk their lives over scraps of glory and modest cash prizes, rather than something as dramatic as national fame or legal freedom.

Is there any basis for this in the source material? The most detailed section on sports from the Cyberpunk 2020 tabletop RPG comes from the ‘Home of the Brave’ source book. “The professional sports industry of the information age needed to be truly global, truly brutal, and truly cathartic for a population of almost five billion humans … It had to be different on a massive scale,” it reads. In Cyberpunk 2020, the most popular sport is a hyper violent, augmented version of American football that leaves some athletes with such severe head injuries that they live on “chipped routines that keep them moving and playing under AI control.”

The most interesting bit of worldbuilding in this section is actually Cyberpunk 2020 bucking dystopian trends. Death sports, it says, are still rare, because “If these players do not have long and illustrious careers, then they cannot recoup their respective companies’ capital investment. Sports stars hock everything from shoes to shuttles, so a short career is not a corporate consideration.” How’s that for bleak?

Cyberpunk 2020’s worldbuilding is dedicated to its wider themes of economic monopoly instead of an easy dystopian checklist. Naturally, it’s difficult for an FPS to make those themes as compelling as in a tabletop world that players can more freely explore, but the racing quests already in the game are a good start, and there’s a lot here for Cyberpunk 2077’s online mode to eventually pull from. This is assuming we’ll get something GTA-online shaped from CD Projekt Red, although that’s definitely where my eddies are.

I do have my own selfish reasons for caring about this sort of thing: I got big, comfy, nostalgic Rock n’ Roll Racing vibes while playing through Claire’s missions. I love combat racing games, love dystopian sport, and feel that CDPR could do a damn fine job of picking up the mantle where Blizzard dropped it years ago. Cyberpunk’s soundtrack is well past the days of chiptune Black Sabbath covers, but burning rubber and blasting much better drivers into scrap whenever they overtake you is some timeless nonsense that I’d love to see in Cyberpunk’s multiplayer.