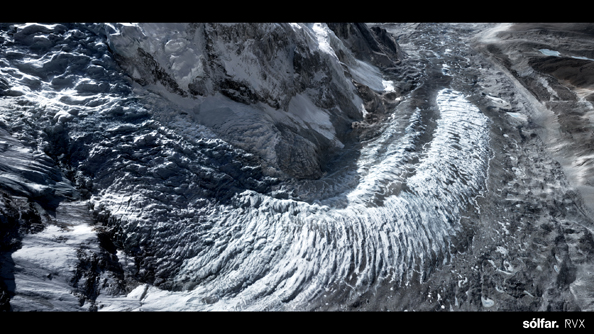

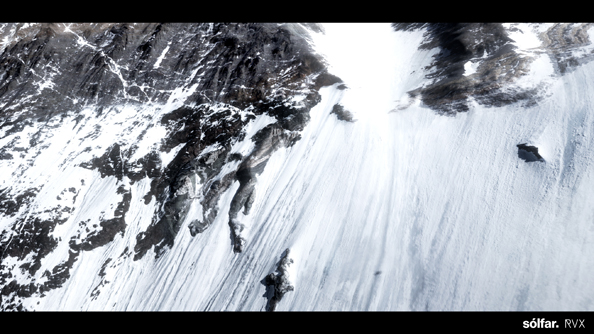

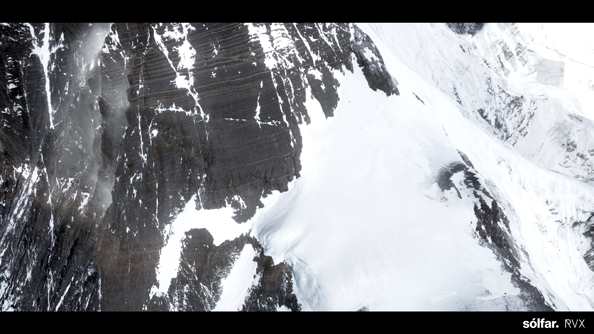

It’s all there. The impossible tracts of snow; countless tonnes piled high and turned up as if ploughed by gigantic machinery. Alien plains of blackened, undulating rock marbled with long-frozen ice, seemingly compressed by the boot of a passing titan. Near-vertical cliffs turned blinding white by a sun you’re never closer to than here. The scale is only visible by dint of the detail, captured via sweeping helicopter shots made familiar by nature documentaries. Only it’s not a helicopter, but the free camera of the Unreal Engine.

“When someone tells you about VR what do you want to do?”, asks Reynir Hardarson, co-founder of Sólfar Studios and, once upon a time, Eve Online’s CCP. “You want to climb Everest, it’s the first thing that obviously comes to mind.”

Remember how The Astronauts scanned pictures of real-life rocks and tree stumps to achieve the extraordinary photorealism of Ethan Carter? Well: Icelandic animation outfit RVX did the same for the highest mountain on Earth – using a GTX TITAN X to catalogue 300,000 high-res images and generate a 3D model of the whole range for Baltasar Kormákur’s Everest, the Josh Brolin film released in September.

Meanwhile, as 15 years of creative direction at CCP came to an end with the cancellation of World of Darkness, Hardarson found himself hankering for a project small enough to be free from management infrastructure.

“It’s like if you’re building a house,” he explains. “If you have three floors you don’t need an elevator, but if you have seven you definitely need an elevator. If you have 30 floors you need like five elevators and at the end, you only have elevators.”

An old colleague showed Hardarson the work being done at RVX, and a few crude tests later, his seven-strong Sólfar Studios were sure that this was the way to showcase VR.

Everest is bigger than games. Consider Mark Zuckerberg’s dream of Oculus Rift users studying in virtual classrooms and consulting with doctors face-to-face. Or the recent Greenlight VR survey of 2,250 US consumers that found 66% wanted virtual travel and exploration from their magic goggles. Sólfar have committed themselves to recreating a real-world experience very few of us will ever see.

In Everest VR, players – or users – will be flown between iconic points on the mountain, and the game – or experience – will tell them the place’s story. You’re on the ground at base camp in first-person, performing a ritual with the crampons and the ice picks. The mountain is a goddess, Sagarmatha, and climbers must ask her permission to pierce her with sharp objects. Then you’re seeing the sun rise from the Hillary Step, the sheer rock face climbers face with fixed ropes on their ascent up the mountain’s South Eastern route. And you’re at the summit, planting a little flag and looking out over the range. The Reykjavik studio are, of course, drawing on their own experience with snow and changeable weather conditions.

We’ll get a one or two hour meeting with the mountain, rather than the 60 hour trek you can otherwise expect.

“The sense of awe you get is a different thing and obviously not the same as being on Everest, right,” says Hardarson. “But it is weirdly close.”

What’s also been weird – even for a director involved for many years with an MMO designed to be “more meaningful than real life” – has been seeing the gamier elements of Everest VR fade into the background during testing.

“You don’t have to solve a puzzle or kill a zombie; it’s just being there and having agency in the world,” Hardarson muses. “For me personally the game elements are really secondary to the experiential feeling. VR is more like a dream experience – it doesn’t have to make sense on a gaming level. I don’t care how many points I score. That’s pointless. It’s more emotionally driven game design than data driven.”

Sólfar have become invisible designers – building systems their players won’t consciously engage with. And yet there’s an agency to Everest VR that’s exceedingly gamelike. In embracing the film world, there must have been a temptation to try and control exactly what their VR climber sees, yet Sólfar are dedicated to letting players control their own pacing.

“Games that push you too hard, they feel like you’re being rushed and it stresses you out,” says Hardarson. “In VR, slow pacing is beautiful because then you can enjoy the environment and look at things and explore. It’s way more different than we anticipated it to be.”

There’s a practical reason for allowing the player to dictate their own movements too. VR’s biggest obstacle to mainstream adoption is the nausea referred to in the nascent industry as simulation sickness. And it’s a tricky bugger, because it’s so subjective.

“Doing VR is kind of like brain hacking,” reckons Hardarson. “We feel like we’re looking into the inner workings of the soul. Sometimes it just doesn’t make any sense, what works and what doesn’t work.”

Elements of Everest VR can be overwhelming for those strapping goggles to their face for the first time. Not least flying around the mountain. For that reason, Sólfar start players off in a virtual room, with Everest confined a cinema screen. Then the screen is taken away, but they find players can cope with that – they’ve had their initial grounding in 3D already.

There are, however, some sicknesses you want.

“Some people just don’t feel it at all and some people are so sensitive to it, but we generally try to increase the sense of vertigo,” says Hardarson. “Because that’s kind of the whole experience of climbing a mountain.”

Everest VR will come to virtual reality platforms next year. Unreal Engine 4 development is now free.

In this sponsored series, we’re looking at how game developers are taking advantage of Unreal Engine 4 to create a new generation of PC games. With thanks to Epic Games andSólfar Studios.