In the beginning was the word – and it was poorly translated. Game localisation, the art of not just translating a game’s text into a new language but shaping it so that the words also make cultural sense, has come a long way.

The first ever example is thought to be Pac-Man. The direct translation from Japanese into US English should have been ‘Puck-Man’, but fears that the game’s literal name would cause childish vandals to deface the arcade machines with obscenity meant that a cleaner sounding ‘80s phenomenon was born instead, and localisation along with it.

Fast forward to the present and, as Stuck In Attic, the developer behind recent point-and-click game Gibbous: A Cthulhu Adventure discovered to its horror, sometimes the ambiguous lines between good and awful localisation don’t just add up to embarrassing mistakes. Sometimes they can come close to ruining your game.

The skill of a true ‘localisation sensei’ (not, I’m told, their official title) is to think about what the essence of a game’s words and phrases mean in its original language and translate that contextual meaning, as opposed to merely the literal one, into the new language too.

As with many nuanced jobs, if the localiser does their job well, you probably won’t even realise the game has one. Get it wrong and games can become laughably absurd. Consider a translator losing the context when localising RPG Grandia 2 into German, and so translating the word ‘MISS!’ – in the sense of not hitting the mark – into the German word ‘FRÄULEIN!’, meaning a ‘miss’ of the unmarried woman variety.

Another example of the importance of good localisation as opposed to direct translation is a well-known in-joke among the adventure games community – that is, the infamous ‘monkey wrench’ puzzle of Monkey Island 2: LeChuck’s Revenge. Players needed to pick up a monkey and use it to tighten a pump to turn off a waterfall – a clever reference to the American term ‘monkey wrench’, referring to a specific type of house tool. Unfortunately, not many people living outside of the US at the time knew of the term. “The tool is called a spanner in England, so the pun (was) lost,” LucasArts designer David Fox recalls. “As a result, people had a terrible time with that puzzle. Puns are the worst.”

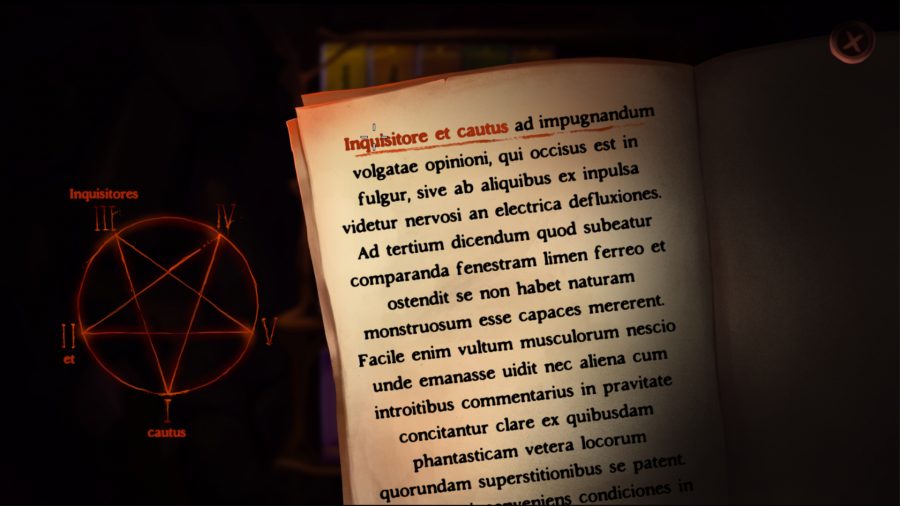

The incident with Gibbous wasn’t quite so funny. The Lovecraft-inspired adventure game features, according to lead developer Liviu Boar, “over 100,000 words,” which he estimates is roughly the length of the Greek epic poem The Iliad. Localising such a long text is no mean feat for even the most experienced translators, and at first, after a successful Kickstarter campaign, the small team’s aim was only to contextualise it into what’s known in the business as ‘FIGS,’ or French, Italian, German, and Spanish, using established freelancers.

But when a company offered the team the chance to localise their game into six more languages, including Russian, Chinese, and Korean, they, perhaps naively, jumped at the chance to showcase their hard work to a wider audience. “What was cool was [that] they were offering languages that not a lot of people localise in,” Boar explains. “Like Arabic for example. […] That was something we were very excited to be able to provide, because those people are just completely ignored on Steam and GOG.”

According to the developer, alarms bells only started ringing a couple of months before the game was due to launch, when the team also localised their Steam page into the same different languages. “We started getting messages from Russian players saying, ‘are you aware that your page reads like it was translated with Google Translate?’” Boar recalls. “We started asking people about the other languages […] it turned out that they were just as horrible too. We were weeks away from release and we had blown all our localising budget.”

Facing releasing a supposedly unintelligible game to the public, and after struggling to fix the issues with the original translation company, the team were forced to scramble together a hodgepodge of freelancers and helpful players to localise the game against the clock. Amazingly, some languages, like Chinese, did get completely retranslated before Gibbous’ launch, due on the most part to well-wishing translators working tirelessly for what Boar admits at this point was very little money.

But not everything could be saved. “We had people who started to fix the Russian and Korean localisation,” Boar says, “but because it was so close to launch, only half of the script was being fixed.” Unsurprisingly, an extremely wordy adventure game written in a half-translated script didn’t go down too well with the community. “If you filter our Steam negative reviews and set it to ‘all languages’ and [type in] ‘Google Translate’, most of the negative reviews are in Russian or Japanese or Korean and they all mention the reason for the negative review being the horrible translation,” Boar says. “When people refund the game, they have the option of leaving a note and the crushing majority of those are ‘I can’t understand it in my language’. It really detracts from the experience – it hurts it. It’s not like it’s neutral. It detracts.”

When asked about the service they provided for Gibbous, the company in question told me that Stuck In Attic’s lack of budget for the TEP (Translation, Editing, and Proofreading) process, and the fact that they didn’t have a copy of the game whilst translating, meant that only “novice translators” were able to work on it.

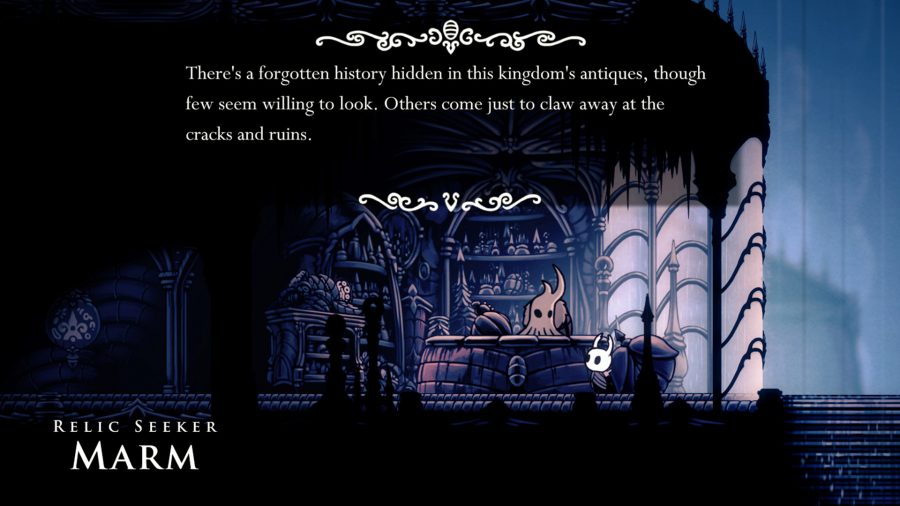

Boar admits that their naivety as a small company working on its first ever game probably didn’t help matters. “Obviously it was our decision to go with these people,” he says, “but we were very doe-eyed. We’re not going to do that again any time soon.” Happily, the game, released in August, still impressed a large amount of those players who were able to play a well-localised version. Boar also tells me that after hiring Alexander Preymak – an experienced game localisation expert whose previous work includes the likes of Thimbleweed Park and Hollow Knight – to rewrite some of the Russian translation, Gibbous is nearly where the team of three wanted it to be before its release.

Fox, whose work after leaving LucasArts also includes Thimbleweed Park and projects like it, points to ways in which new developers like the Gibbous guys can make their lives easier if they want to localise. Most importantly, make sure your text can be isolated in a separate file, which can be replaced when adding a new language.

As for Preymak himself, his advice for developers who want to localise their games effectively is threefold: write your text with the translation in mind, think of your fonts – particularly if translating into languages that require a different alphabet, such as Cyrillic – and make your LocKit (localisation kit – a briefing pack for translators working on your game) accessible to work with.

And when it comes to localising games with puns in them? “God forbid you do so,” jokes the Russian, before adding, “consult a professional translator!” If only it were always so simple.